The Power of Fermentation: Enhancing Japanese Cuisine

Mar 26,2020

The Power of Fermentation: Enhancing Japanese Cuisine

Mar 26,2020

Washoku, traditional dietary cultures of the Japanese, was inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2013. Fermentation is inseparably intertwined with the evolution of Japan’s dietary culture. The Japanese have applied fermentation techniques in myriad ways, from making basic seasonings like soy sauce and miso to brewing the many varieties of sake produced all over the country. But because fermentation is such a familiar part of Japanese life, many people are unsure of how fermentation works, its practical uses, and its close links to Japanese food culture.

The National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo is about to host a special exhibition on washoku or traditional Japanese cuisine. This will be the first major exhibition to explore the subject from a multitude of angles. It will showcase the foods and fermentation techniques that have evolved in Japan’s natural environment. It will also trace the history of washoku from ancient times, with an eye to its future.

The exhibition is entitled Washoku: Nature and Culture in Japanese Cuisine. The displays on fermentation are curated by Dr. Hosoya Tsuyoshi, who shared with us his detailed knowledge of the fermentation techniques in which the Japanese take such pride.

Dr. Hosoya Tsuyoshi, a skilled explainer, also lectures at the Universities of Tsukuba and Tokyo.

Dr. Hosoya Tsuyoshi is curating the displays on fermentation at the special exhibition Washoku: Nature and Culture in Japanese Cuisine to be held at the National Museum of Nature and Science. Currently with the Division of Fungi and Algae of the Museum’s Department of Botany, he previously worked for a pharmaceutical company.

“I studied fungi at university and graduate school, then worked at a pharma company for sixteen years. There I had the task of discovering molds that were useful to humans. A lot of molds are already being put to good use—koji fungus and penicillin, for example. My job was determining whether there were any molds that weren’t being used yet, and if there were, collecting them and identifying what they could do. I joined the National Museum of Nature and Science in 2004, and I’ve spent half my career here now. I suppose I have a bit of an unusual background for someone who works at a museum.”

Dr. Hosoya has spent years studying fungi, and he describes fermentation, which plays a key role in washoku, as a remarkable technology invented by humans.

“Many Japanese foods are fermented, including natto and miso. Fermented foods aren’t edible organisms that can be harvested in the ordinary way. They’re foods that last longer or have greater nutritional value or taste better because they’ve undergone secondary changes. Such production of substances useful to humans through the action of microorganisms is known as ‘fermentation.’ Rot, on the other hand, is harmful to humans. But as far as the microorganisms themselves are concerned, fermenting and rotting are the same thing.

“The natural world is teeming microorganisms, so if you leave food lying around somewhere, it’s liable to rot. But humans have since ancient times skillfully manipulated microorganisms invisible to the eye and utilized them to prevent substances from rotting and make them useful to us. Fermentation is an amazing technology invented by humans.”

Of all the microorganisms that facilitate fermentation, koji fungus is the most indispensable to the Japanese diet. Koji fungus is widely used for common condiments like soy sauce, miso, and sake, as well as for koji amazake, a sweet fermented beverage that has been attracting the limelight lately.

“Fermentation, as I’ve just mentioned, is about manipulating and utilizing microorganisms. Typical examples are Japanese pickles and cheese and yogurt, all of which are produced when humans create the right temperature, moisture, and other conditions. But making soy sauce, miso, and koji amazake takes more than just the right environmental conditions. Koji fungus must be added as well. So koji fungus isn’t just the product of happenstance. Industrially speaking, it’s a highly advanced technology.”

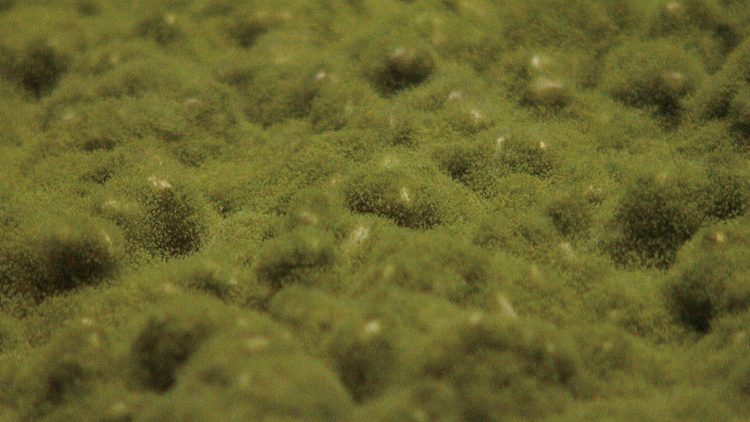

A specimen of bara (loose) koji—something of a rarity

There are over a hundred varieties of koji fungus. The variety chiefly used in Japan is called rice koji, which is produced by growing koji mold on rice. And Japan is the only country in Asia where koji is used in the form of bara koji or “loose koji,” in which the rice grains retain their shape. It dates back more than a thousand years.

“The origins of koji are obscure, but we know that koji merchants already existed during the medieval Muromachi period, and the imperial court and the shogunate regulated its distribution. Going further back, ancient Nara-period sources record that rice inoculated with mold was used to make sake.

“In fact, rice koji isn’t even found in the natural world. It’s made from a substance called tane koji or ‘koji starter.’ Koji starter was first developed between the late twelfth and the thirteenth century, and there are only a handful of companies that make it today, even in Japan.”

Koji starter made by growing koji mold on rice coated with wood ash

Koji is classified into several different types. The main types used are yellow koji, white koji, and black koji. In Japan, the koji used differs depending on region, climate, and what it’s used for.

“Alcohol beverages are a good case in point. Sake is made in northern regions using yellow koji, while shochu and awamori become more common the further south you go. Shochu is made using black koji. This produces citric acid, which keeps out bacteria due to its high acidity. In southern regions like Kyushu and Okinawa, the variety of koji best suited to the hot, steamy climate apparently came to be used.

“Different types of koji are used to make different things. Soy sauce koji mold is used to make soy sauce, and awamori koji mold is used to make awamori.”

“Koji is the basic determinant of a fermented food’s taste,” according to Dr. Hosoya. But other factors are also important in defining the ultimate flavor.

“Take sake, for instance. Sake is made with just three ingredients—rice, koji, and water—yet it comes in many different flavors. This variety results not just from the different types of koji used but from the interplay of various factors, including the type of rice used and the way water differs from region to region. Similarly, soy sauce and miso taste completely different depending on the environment. There are also regional differences in how the ingredients are prepared for fermentation.

“Japan, stretching as it does from Hokkaido in the north to Kyushu and Okinawa in the south, is a climatically diverse country, and each climate zone is inhabited by different organisms. Hance most foods have evolved in a way suited to the local climate and geography. Fermented foods are a case in point.”

Besides exploring the subject of fermentation, the special exhibition Washoku: Nature and Culture in Japanese Cuisine will feature displays on ingredients indispensable to Japanese cuisine like water, vegetables, fish, mushrooms, and seaweed. It will also trace the history of washoku from the prehistoric Jomon period through modern times. The range of exhibits is impressive.

The special exhibition will explore washoku from a multitude of angles

“This exhibition will, I think, give visitors a better understanding of biodiversity in Japan. Biodiversity comprises species diversity, genetic diversity, and ecosystem diversity. It means all three are in balance.

“To describe the natural world is also to describe washoku. After all, the vegetables, fish, and shellfish harvested in a particular place will vary depending on the ocean currents and the character of the soil and water. Washoku has also evolved by making use of fungi like koji and incorporating new technologies. This exhibition will, I hope, give visitors an idea of the wonders of washoku and the cultural traits of the Japanese people.

“Sake, soy sauce, miso, and other traditional Japanese foods are packed with advanced technologies developed by the Japanese. Understanding how they’re made will change your impression of Japanese cuisine—not to mention the condiments you use every day without a second thought!”

PhD

PhD

Besides being on the staff of the National Museum of Nature and Science, Dr. Hosoya is also professor in the School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba. An expert on fungi, he spends his days busily searching for undiscovered and unrecorded species of fungi.

Special Exhibition WASHOKU: Nature and Culture in Japanese Cuisine

Dates: Beginning soon (date to be announced) and on until Sun. Jun. 14, 2020

Venue: The National Museum of Nature and Science, Ueno Park, Tokyo

Hours: 9:00 am-5:00 pm (8:00 pm Fridays and Saturdays). Last entry 30 minutes before closing.

Open until 8:00 pm Sun. Apr. 26, Wed. Apr. 29, and Sun. May 3-Tue. May 5.

Open until 6:00 pm Mon. Apr. 27, Tue. Apr. 28, Thu. Apr. 30, and Wed. May 6.

Closed Mondays, Thu. May 7, and Tue. May 19.

The museum will be closed Mon. Mar. 30, Mon. Apr. 27, Mon. May 4, Mon. May 18, and Mon. Jun. 8.

Please note that opening times and dates closed are subject to change without notice.

For ticket prices and other details, please visit the official exhibition website WASHOKU: Nature and Culture in Japanese Cuisine.