Tanabata and Somen Noodles: A Festive Connection

Jun 24,2021

Tanabata and Somen Noodles: A Festive Connection

Jun 24,2021

The Tanabata Festival is held on July 7, or the seventh day of the seventh month. According to legend, this is the only day of the year on which the lovers Orihime and Hikoboshi—the Weaver Girl and the Cowherd—can meet, for they are separated by the Milky Way. Many Japanese have fond memories of being read stories about the pair’s long-awaited encounter. It is the custom on Tanabata to write wishes on paper strips and hang them on bamboo branches.

In this new series “Traditional Seasonal Festivals of Japan,” we’ll be asking food culture expert Kiyoshi Aya about events on the traditional Japanese calendar, their historical background, and the foods and cultural traditions associated with them. The subject of the first installment is Tanabata.

“Tanabata is one of the five seasonal festivals derived from the traditional calendar borrowed from ancient China. The five seasonal festivals are: the Festival of the Seven Herbs or Jinjitsu Festival on the seventh day of the first month; the Doll Festival or Joshi Festival on the third day of the third month; the Iris Festival or Tango Festival on the fifth day of the fifth month; the Tanabata Festival or Shichiseki Festival on the seventh day of the seventh month; and the Chrysanthemum Festival or Choyo Festival on the ninth day of the ninth month. The five seasonal festivals originated in ancient China, where dates that repeated the same odd number, such as the third of the third or the fifth of the fifth, were considered unlucky. Ceremonies were therefore held on those dates to expel evil spirits. To put it in modern terms, it was like holding a special event to pray for everyone’s health at the changing of the seasons, when people tend to feel under the weather.”

The five seasonal festivals are in Japanese called gosekku, which is today written two ways in kanji: either 五節句, meaning “the five seasonal divisions,” or 五節供, meaning “the five seasonal offerings.” The latter is the original meaning, according to Aya.

“The five seasonal festivals originated as occasions on which people ‘offered’ the bounty of the season to the gods and buddhas, then shared the food among themselves after the ceremony. They thus fortified themselves with the foods of season while praying for good health. That’s why it’s correct to use the kanji for ‘offering’ to write the word.”

Food culture expert Kiyoshi Aya

How then did the Tanabata festival emerge in Japan as one of the five seasonal festivals?

“The Japanese ceremony of Tanabata evolved into its present form as many different cultural traditions and practices became fused over the centuries. These include the legend of the Chinese Star Festival, the ancient Japanese cult of the Water God, and the custom of honoring dead ancestors at the Bon festival.”

According to the famous legend of the Star Festival, the Weaver Girl and the Cowherd are lovers who can cross the Milky Way but once a year to meet. This tragic love story had emerged in China by the first century. The complete plot of the story is already found in the sixth-century Chinese handbook Festivals and Seasonal Customs of the Jing-Chu Region.

“In China, a festival called the Qiqiao Festival was celebrated on the seventh day of the seventh month, the day of the lovers’ meeting. The Weaver Girl was the patroness of thread and needlework, and on this day she was honored with prayers for greater skill in handicrafts and weaving.

“In Japan, meanwhile, there was the legend of Tanabatatsume, the Weaving Maiden. According to this ancient Japanese legend, the Weaving Maiden would seclude herself in a hut between the sixth and seventh day of the seventh month. There she would weave a sacred garment to present to the Water God when he descended from heaven.

“The Chinese festival, with its associated legend, had already reached Japan by the Nara period (710-784) and been adopted by the Japanese nobility. It then spread while merging with the native Japanese legend of Tanabatatsume and the cult of the Water God. That, according to one theory, is why the festival came to be called Tanabata.”

Over a dozen poems on the theme of the Weaver Girl and the Cowherd are found in the Manyoshu, an anthology dating from the end of the Nara period. In the Nara and subsequent Heian (794-1185) periods, Tanabata became established as a ceremony where nobles prayed to improve their artistic skills. Then in the Edo period (1603-1867), it spread to the common people.

“Ukiyo-e prints of the Edo period show the city adorned with bamboo plants towering above the rooftops and bamboo branches being festooned with strips of paper. During the second half of the Edo period, the people of Edo (as Tokyo was then called) evidently celebrated festivals in much more style than Japanese do today.”

Edoites celebrating Tanabata. “The Tanabata Festival in the Great City of Edo,” from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji. Tokyo National Museum (TNC). Source: ARC Ukiyo-e Portal Database.

And what food did the people of Edo use for offerings and celebrations on Tanabata? Somen, or thin wheat noodles.

“Eating somen on Tanabata and giving it as a gift had become well-established customs in Edo by the second half of the Edo period. Sources also record that by the first half of the Edo period, Tanabata was already being celebrated in Kyoto, where the nobility had emerged centuries before, by eating somen and holding poetry readings.”

But somen hadn’t always been eaten at Tanabata, Aya adds.

“Nobles had initially offered a type of pastry called sakubei on the altar. Sakubei, which originated in China, is made by kneading wheat flour, twisting the dough into spirals, and then frying or boiling them. This, they say, eventually evolved into what is now somen and came to be offered on Tanabata.”

Today somen is standard summer fare for ordinary Japanese. Back in the Edo period, though, it was still a luxury. Somen was widely available in Edo, which was a huge city, but other parts of the country had their own Tanabata traditions.

Sakubei, believed to be the precursor of somen noodles

What then did people in communities other than Edo offer and eat on Tanabata? Shokoku fuzoku toijo kotae (Answers to questions on regional customs), a survey of mores and customs in different parts of Japan dating to c. 1815-16, contains several pertinent entries.

“It records, for instance, that in the province of Bingo (the region around Fukuyama in present-day Hiroshima Prefecture), melon or watermelon was offered at Tanabata. It makes little mention of somen being offered in rural regions, where offering summer vegetables was apparently the norm. There were also regions like Fukushima where udon noodles were produced as an offering.

“Offering things like these at Tanabata, I think, makes sense when you consider the idea behind the five seasonal festivals. They’re occasions on which to offer and enjoy the bounty of the seasons and pray for good health.

“Another thing: the five seasonal festivals were traditionally held according to the old lunisolar calendar. In some regions of the country, they’re still celebrated by the old calendar in association with Shinto festivals. The Gregorian calendar used in Japan today is, to the traditional Japanese way of thinking, out of sync with the actual seasons and the foods they yield.”

Tanabata decorations display clear regional differences as well.

“In Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture, the tradition of hanging what are called ‘Tanabata dolls’ from the eaves lives on today. And in Susaki, Kochi Prefecture, and parts of Chiba, it’s customary to decorate the home with horses or cows made of straw. These are called ‘Tanabata horses’ or ‘straw horses.’ In some areas, Tanabata is celebrated as part of the Bon festival rites.”

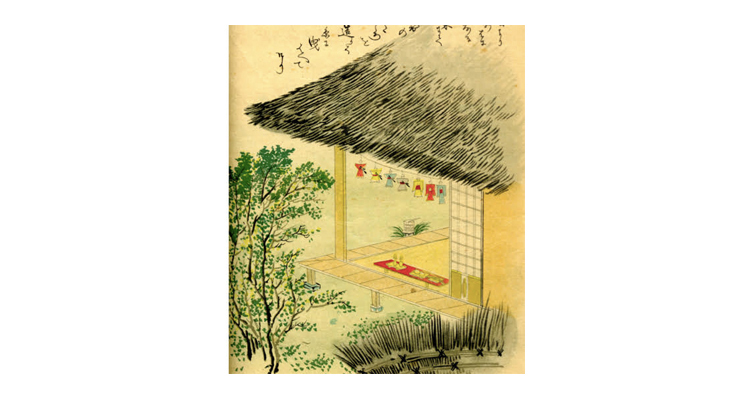

Tanabata dolls suspended from the eaves. From Sugae Masumi’s travelog Masumi Yuran-ki. Source: National Archives of Japan Digital Archive.

Thus Tanabata came to be celebrated among the common people in the city of Edo and throughout Japan. After the Meiji Restoration, though, the five seasonal festivals largely lost their festive air as they ceased to be special days on the calendar.

“The Peach Festival and the Tango Festival have survived in the form of the Girls’ Festival and Children’s Day because of their character as rites of passage for children. But Tanabata and the Chrysanthemum Festival were largely forgotten. Then Tanabata was revived in the classroom at kindergarten and elementary school and is now honored by writing wishes on strips of paper. And the famous Sendai Tanabata Festival was established after the war as a community event. Today it attracts tourists in droves.”

Aya says she hopes that these traditional celebrations will live on in many forms.

“Japanese still eat rice porridge with seven herbs on January 7 and celebrate the Doll Festival, Children’s Day, and Tanabata. The five seasonal festivals are still very much part of our lives. But it’s seldom realized that these festivals originated in a desire to pray for peace and good health and expel evil spirits at the changing of the seasons. That’s their original ceremonial significance, and they have endured because of this very human urge. Keeping that historical background in mind as we celebrate each of these festive days can, I believe, help enrich our lives. But there’s no need to get too serious. These traditional festivals will hopefully continue to be fun occasions for kids and the entire family. More and more supermarkets and specialty stores these days advertise somen for Tanabata. And websites and cookbooks now feature somen recipes with fun garnishes like vegetables cut into stars. That’s a great way to enjoy Tanabata, one of the five traditional seasonal festivals of Japan.”

A “Tanabata horse” made of straw

food culture researcher

food culture researcher

food culture researcher and Secretary of the Research Division at the National Council for Washoku Culture

Born in Osaka prefecture, Kiyoshi is involved in researching traditional regional Japanese cuisine and the dietary habits in fishing and farming communities as well as writing and giving lectures about local foods.

Recent publications include Washoku Techo [Washoku Handbook] (co-author, published by Shibunkaku), Furusato no Tabemono [Hometown Food] (Washoku Culture Booklet No. 8) (co-author, published by Shibunkaku), and Shoku no Chizu [Maps of Food], Third Edition (published by Teikoku-Shoin).