Soy Sauce Preserving Culinary Heritage in Nagano

Oct 03,2024

Soy Sauce Preserving Culinary Heritage in Nagano

Oct 03,2024

Nagano Prefecture, home of the Japanese Alps, is nicknamed the Roof of Japan because of its towering peaks. The low-lying stretches of land between mountain ranges are known in Nagano as daira or “plains.” There are four main ones: Zenkoji-daira, Matsumoto-daira, Saku-daira, and Ina-daira. Each has its own history and thriving cultural traditions. The southernmost of the four, Ina-daira, forms a long, narrow valley. It extends eighty kilometers from Tatsuno in the north to Minamishinano in the south, and is ten kilometers wide from east to west. It is also known as Ina Valley. In almost the middle of the valley is the city of Komagane, where Ina Soy Sauce is located. This beloved local institution has long made the soy sauce indispensable to Ina Valley’s cuisine. To find out more, we interviewed the company’s president, Yoneyama Hiroshi.

Soy sauce is, along with miso, the quintessential Japanese condiment. But not all soy sauces are alike. All over Japan, soy sauces in different regions have their own distinctive flavor and character. Each soy sauce has evolved a flavor adapted to the regional food culture. Ina Soy Sauce was founded in 1942 to preserve such local culinary traditions.

“Sourcing ingredients for making soy sauce was no easy task in those days,” explains Mr. Yoneyama, “because of the strict controls imposed during the Pacific War (1941-45). The way things were going, soy sauce producers wouldn’t even be able to make soy sauce anymore. So sixteen soy sauce dealers in what is called the Kami Ina (Upper Ina) region, which extends from Tatsuno to Nakagawa in the Ina Valley, banded together of their own accord. They pooled supplies and built a joint factory. They also set up a company to procure ingredients and handle production and distribution. That company was Ina Soy Sauce (then called the Kami Ina Soy Sauce Brewery Cooperative).”

The Yoneyama family firm Yoneyama Soy Sauce and Sake was one of the sixteen dealers. The new enterprise was organized as a cooperative. That meant it was jointly run by the member companies, each of which remained a separate entity.

“Ina Soy Sauce’s first president of was a gentleman named Mr. Hanaoka. He was president of Hanaoka Kaneharu Shoten, which had been making miso and soy sauce in Tatsuno since the Taisho era (1912–1926). Their trademark was Maruki-jirushi. Incidentally, when they transferred their soy sauce making operations to Ina Soy Sauce, they spun off a separate company devoted to making miso. That was Hanamaruki Miso. Anyway, my grandfather succeeded Mr. Hanaoka as the second president. My father was the fourth president, and I’m now the sixth president. So members of my family have alternated in the top position.”

Ina Soy Sauce was jointly established by sixteen soy sauce dealers in the Kami Ina region to supply soy sauce to their respective communities.

The idea of a group of manufacturers teaming up to form a company was still new in those days. The joint factory they set up in the city of Ina (today Komagane) was designated as a model by the prefectural government. In 1949, it established a new method of production.

“Things began to really change when my father was in charge. That was during the rapid-growth years, when the Japanese economy was starting to modernize. My father went to the National Tax Agency Brewing Research Institute (now the National Research Institute of Brewing), which was then on the cutting edge, to learn the latest technology. The company’s soy sauce had until then been entirely naturally brewed. Now my father adopted a new form of brewing using amino acids, as well as a technique called ‘quick fermentation.’ This made it possible to manufacture soy sauce year-round. Here’s how soy sauce was made. First you steamed the soybeans and roasted and crushed the wheat. Then you added koji fungus to make the koji malt. This was combined with brine to make the moromi mash. The mash had to be tended to virtually every day for six months to a year. You had to keep mixing it while paying attention to the temperature and humidity. Manufacturers would put a lot of time and effort into making the koji and the mash. And because the soy sauce was naturally brewed, it was a struggle to achieve consistent quality.

“My father therefore adopted the practice of purchasing what’s called ‘raw soy sauce’ — soy sauce pressed from mash that’s finished aging. This move saved labor, money, and time and made it possible to provide the community with a steady supply of low-priced soy sauce of consistent quality. Of course, there were still steps that required a craftsman’s skill. Raw soy sauce can’t be sold as is. It has to be blended and pasteurized before it’s shipped. Pasteurization doesn’t just remove microbes. It also serves to adjust the color, flavor, and especially the aroma, which are all vital to a soy sauce. The slightest difference in temperature or pasteurization time affects how the soy sauce turns out. Getting it just right separates the men from the boys.

“What’s called ‘mixed soy sauce’ has long been a favorite of people in the Ina Valley. To make this, you finish up by blending in an umami-enhancing amino acid solution to create a balanced flavor. I’ve been told that it took a fair amount of effort to come up with the right ratio to achieve the same flavor as old-fashioned Ina Valley soy sauce.”

The Ina Soy Sauce factory with its row of massive tanks. The city of Komagane, sandwiched between the Central Alps to the west and the Southern Alps to the east, is famed for its spectacular views of both ranges.

On examining Ina Soy Sauce’s product lineup, you’ll notice that there are two types of soy sauce depending on how the soy sauce is made: kongo or “mixed” soy sauce, and honjozo or “traditionally brewed” soy sauce. Mixed soy sauce is made by adding an amino acid solution to raw soy sauce, then pasteurizing it. Honjozo soy sauce is made by pasteurizing raw soy sauce without the addition of an amino acid solution. An amino acid solution is a liquid made by hydrolyzing soybeans or wheat with hydrochloric acid or enzymes. Such solutions are widely used in the food industry. Adding an amino acid solution imparts umami and richness.

“Which soy sauce you think tastes better is a matter of personal preference, but in the Ina Valley region, people tend to be prefer mixed soy sauce with its umami kick. Our most popular soy sauce is our light-colored mixed soy sauce Shirafuji, which accounts for some 60 percent of our sales. In November, the season for pickling nozawana — a type of mustard green that is a local favorite — shipments increase several-fold over their usual level. At retail outlets, many shoppers buy several bottles in one go, and it sells out in no time. There are still a lot of households in this area that buy nozawana and pickle it at home, and the soy sauce they use is Shirafuji. Quite a few people even say that pickled nozawana doesn’t taste right unless it’s made with Shirafuji. And many folks say they use it not just for nozawana but for everything: stewed dishes, stir-fries, grilled fish, chilled tofu, raw egg on rice, you name it. There’s even someone who says they make soup by putting dried wakame and pieces of wheat gluten in a bowl and adding Shirafuji and hot water. Even without stock, it tastes great because it packs so much umami.”

Mixed soy sauce is common in Kyushu and the Hokuriku region. The sweet version made in Kyushu is especially unusual. Besides amino acid solution, it also contains sugar or sweetener. Mixed soy sauce, it’s fair to say, emerged from attempts to devise a flavor the locals would love.

Here’s how nozawana pickles are usually made in the Ina Valley. Put the washed nozawana greens in a container. Add sugar and vinegar while drizzling on Shirafuji soy sauce. Place a drop lid over the greens and put a weight on top. If the nozawana are still at their full length, they’re ready to eat in fourteen to fifteen days. If sliced into five-centimeter lengths, they’re ready to eat in about five days. Use one liter of Shirafuji, 400-500 grams of sugar, and 500 milliliters of vinegar per seven kilograms of nozawana.

Left: Pickling nozawana begins in November.

Right: Komagane is famed for Sauce Katsudon — breaded pork cutlet on rice with a savory sauce. Popular eatery Chasoba Inagaki serves it with an Ina Soy Sauce-based sauce.

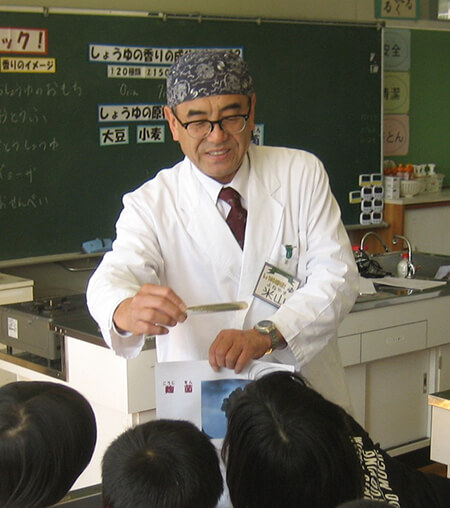

Besides serving as president of Ina Soy Sauce, Mr. Yoneyama wears another hat. He is a Soy Sauce Expert certified by the Japan Soy Sauce Brewers’ Association. As such, he has for the past decade been visiting local elementary, junior, and senior high schools, vocational schools, and sundry other facilities to teach children and adults alike about soy sauce. He heads to these classes attired in a white coat with a bandana on his head.

“Students really enjoy these classes. I want them to learn what soy sauce is made from, so I show them samples from each stage of production and get them to touch them for themselves. That way they can see how the ingredients (soybeans, wheat, and salt) change over the course of production. I also get them to compare the aroma and taste of moromi mash, the raw soy sauce pressed from it, and store-bought soy sauce. I believe in learning about soy sauce through the senses.

“But the person who’s learned the most may be me. That’s because teaching these classes has brought home to me how little people know about soy sauce. For starters, not many people know something so basic as what soy sauce is made from. When I ask, everyone manages to come up with soybeans and salt. But hardly anyone can name wheat. Some people are even surprised to learn that soy sauce is fermented, which is a real shock for a soy sauce maker like me [laughs]. What most surprised me, though, was when I was teaching some third graders and asked, ‘Do any of you have a soy sauce dispenser on your dining table at home?’ None of them did. Far from it, they even asked me, ‘What’s a soy sauce dispenser?’ It was a culture shock to realize that the very term ‘soy sauce dispenser’ has become obsolete. And no wonder it has, since soy sauce sold in small bottles is the norm these days. That’s what makes teaching these classes so rewarding.

People who are into cooking often ask Mr. Yoneyama the difference between dark and light soy sauce.

“Soy sauce is classified into five types: koikuchi or ‘dark’ soy sauce, usukuchi or ‘light’ soy sauce, tamari soy sauce, saishikomi or ‘double-brewed’ soy sauce, and shiro or ‘white’ soy sauce. Each has its own characteristics. It’s worth knowing which to use in which type of cuisine, because that way the food taste better.”

Mr. Yoneyama is a certified Soy Sauce Expert. As such he visits local schools and facilities teaching about soy sauce and its wonders.

We asked Mr. Yoneyama about the five types of soy sauce and what foods each is suited to. Here’s a summary of what he told us.

Koikuchi (dark) soy sauce: The most common form of soy sauce. An all-purpose seasoning offering a nice balance of flavor and umami, it accounts for some 80 percent of the soy sauce consumed in Japan. Perfect for nimono (stewed dishes), yakimono (grilled dishes), and dipping or drizzling.

Usukuchi (light) soy sauce: A light-colored soy sauce emanating from the Kansai region. It contains about 10 percent more salt than koikuchi. Perfect for dishes showcasing the natural flavor of the ingredients, such as takiawase (assorted simmered foods) and fukumeni (foods simmered in broth).

Tamari soy sauce: A thicker type of soy sauce with a rich umami flavor and distinctive aroma, produced chiefly in the Chubu region. Perfect for dipping or drizzling on sushi or sashimi. Also great for teriyaki and tsukudani (preserves made by simmering ingredients in sweetened soy sauce).

Saishikomi (double-brewed) soy sauce: A specialty of the Sanin region and Kyushu. It has a rich color, flavor, and aroma. Mainly used for dipping or drizzling on sushi, sashimi, chilled tofu, and foods like that.

Shiro (white) soy sauce: An amber-colored soy sauce produced mainly in Hekinan, Aichi Prefecture. Despite its mild flavor, it is quite sweet and has a distinctive aroma. Use to achieve a lighter color in dishes like chawanmushi (savory egg custard) and kishimen noodles.

“Soy sauce’s great flavor isn’t the only wonderful thing about it, either. It also masks the raw smell of sashimi and meat, for example, and kills bacteria so foods last longer. When you grill onigiri rice triangles or make fried rice with soy sauce, you get this wonderful mouthwatering aroma the instant you start cooking. When eating dried fish or pickled vegetables that are over-salty, just add a touch of soy sauce and voilà! it alleviates the saltiness and enhances the flavor. What’s more, soy sauce is easy to pair with other seasonings. It can be combined with sugar to make broth for sukiyaki or sauce for mitarashi dango (skewered rice dumplings). It can be combined with vinegar in spring rolls, shumai, or sunomono (vinegared salad). It can be combined with mirin (sweet rice wine) in nimono (stewed dishes) or in the broth for udon or soba. It also goes perfectly with katsuobushi (dried skipjack tuna flakes), butter, or mayonnaise. Is there any other seasoning that can do all that? I plan to keep getting out the message about soy sauce and its wonders while spreading the word about the joys of eating well.”

Mr. Yoneyama certainly has a point. Maybe it’s time to remind ourselves of what a versatile seasoning soy sauce is and the qualities that make it great. The insights that Mr. Yoneyama has gained giving classes as a certified Soy Sauce Expert inform his thinking not just about the local community but also about the future of the Japanese diet.

“Washoku — the time-honored everyday Japanese diet, typified by a combination of dishes called ichiju sansai — was inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2013. I can’t help feeling that being selected for that list means if anything that washoku is considered endangered. Ichiju sansai is a meal consisting of rice, miso soup, and three accompanying dishes such as stewed vegetables. Traditionally, each household had its own recipe for the miso soup and accompanying dishes. The resulting taste was called o-fukuro no aji, literally ‘Mom’s flavor,’ though it wasn’t necessarily mom who did the cooking. The word for ‘mom,’ o-fukuro, has the honorific prefix ‘o.’ These days, though, everyone buys retort-pouch foods and ready-to-eat foods and deli items. I hate to sound harsh, but it’s like the ‘o’ has dropped out, so it’s now fukuro no aji — ‘bagged flavor.’ The traditional taste of washoku is being lost, and we who are alive today have a duty, in my view, to pass it on to the next generation. I intend to continue getting out the message about the importance of diet through the medium of soy sauce. I’m a soy sauce maker, after all.”

From left: 1 liter and 100 ml bottles of Shirafuji (blended), an usukuchi soy sauce synonymous with the Ina Valley; 1 liter and 100 ml bottles of Fuji (traditionally brewed), an all-purpose high-end koikuchi soy sauce; 1 liter bottle of Shiragiku (blended), a mass-market usukuchi soy sauce; 180 ml bottle of Gyoja Ninniku Soy Sauce, which with its abundance of gyoja ninnniku (Siberian onion) goes well with meat; and 1 liter bottle of Kiku (traditionally brewed), a mass-market koikuchi soy sauce.

Yoneyama Hiroshi is president of Ina Soy Sauce Co., Ltd., and heads the Nagano Prefectural Federation of Soy Sauce Manufacturers Cooperatives. He also devotes himself to educating people about diet as a Soy Sauce Expert certified by the Japan Soy Sauce Brewers’ Association. In that capacity he visits local schools and other facilities giving classes on the magic of soy sauce.

Ina Soy Sauce produces usukuchi, koikuchi, tamari, and shiro soy sauces, Gyoja Ninniku Soy Sauce, and pickle starters (speedy pickling mix, misodamari, and nozawana pickling mix).