Learn About Japanese Tableware and Chopsticks for an Authentic Dining Experience

Apr 10,2015

Learn About Japanese Tableware and Chopsticks for an Authentic Dining Experience

Apr 10,2015

The fine details and motifs found in many Japanese utensils tell their own intricate tales. If you turn your attention to these elements and take in the messages they contain, it will surely heighten your enjoyment of Japanese cuisine. With this in mind, we spoke to food researcher Kubo Kanako about the different types of chopsticks and how to better appreciate tableware.

The chopsticks that come with bento boxes and the chopsticks provided at restaurants are made from a variety of materials and in a variety of shapes. Kubo arranged a few pairs for us and explained the differences.

“The first pair are everyday wari-bashi (splittable chopsticks) that you find at set-meal restaurants or that are given to you at convenience stores. The ones with a groove inscribed where they are to be split are called genroku. The surfaces and corners are rounded to make them easier to split apart. They can be classified even further by how the corners are chamfered and by their length.

“The second pair are called tensoge-bashi. They are splittable chopsticks with a diagonal taper at the ten — the end held in the hand. Only the section that grips the food is rounded. This design is to prevent people from using the sticks upside down. Tensoge-bashi have a somewhat formal aspect to them.” They may be made from bamboo, wood, or other materials, but those made from cedarwood are considered to be the highest grade.

“The third pair are called rikyu-bashi and are said to have been concocted by the tea master Sen no Rikyu in the Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568 to 1600).” The name is derived from the story that Sen no Rikyu, on mornings when he expected guests, would taper both ends of each chopstick with a small knife to make them easier to eat with. He would prepare just enough chopsticks for the number of guests. The finest rikyu-bashi are akasugi chopsticks made from red-tinted cedar trays and are perfect for entertaining guests.

“The fourth pair are iwai-bashi [festive chopsticks]. These round chopsticks are finely tapered at both ends and thick in the center. They are also called yanagi-bashi because they are made from the wood of yanagi [willow trees] that resists breaking or cracking, which would be a bad omen at a festive occasion.” There are several other names for these chopsticks. For example, dishes celebrating the New Year, such as o-zoni [rice cake soup], are made not only for people to eat but also to offer appreciation to the gods. The idea of shinjin-kyoshoku communal eating by people and the gods — in which people eat from one end of the chopsticks and the gods from the other — gave rise to the name ryokuchi-bashi [both-ends chopsticks]. Another name is tawara-bashi [bale chopsticks] because the thick middle of the chopsticks resembles a plump rice bale, a sign of a good harvest.

“Japanese people put a lot of sentiments into the objects they create, and chopsticks are no exception. The shapes and materials have meaning, as do the various names given to them. If you know the names and understand the significance of the various chopsticks you see every day, your interest in chopsticks will likely grow.”

Kubo also explained the length of chopsticks. “Hitoata-han is the term for measuring the length of chopsticks that fit you best. Hitoata is the distance spanned by the tips of the thumb and index finger when outstretched to form a right angle. Multiply this distance by 1.5 to get the perfect length of chopsticks for your hand. Chopsticks come in various lengths, such as 16.5 cm, 18 cm, 21 cm, and 24 cm, so look for the size that best fits your hand.”

Have you ever wondered when placing a bowl on a dining table, which side to face toward the guest? We asked Kubo for pointers. “Most bowls and other tableware actually do have a front side. Japanese tableware, in particular, come in many different shapes, so their placement is determined by their shape. With a single-spout bowl, for example, it should be placed with the opening pointing to the left. And if a bowl is shaped like the leaf of a tree, the stem should be on the right and the tip of the leaf on the left. Fan-shaped tableware with a handle should be placed with the handle on the right side. The general rule is to place tableware in deference to their natural shape so the right hand can grasp them with ease for serving or pouring.”

To the left, in this case, does not mean left exactly horizontal to the table. The tableware are fine as long as they are placed facing in the left direction.

Kubo added: “Warizansho is a type of bowl shaped to resemble sansho Japanese peppercorns that have split open in autumn. These bowls should be placed so the split faces the diner, as if to reveal the fruit within. Another rule is that tableware with three legs, like a warizansho bowl, should be placed with one leg in front of the other two.”

Expressing the seasons is an essential part of Japanese cuisine, and this extends to tableware as well. Many dinnerware have patterns and shapes that represent a season.

“For instance, a bowl with a lid decorated with beautiful cherry blossoms is naturally a bowl for springtime use. With tableware like this, the design of the bowl and the lid are contiguous, so the bowl should be placed with the designs aligned and in full view. Tableware with cool, refreshing scenes like medaka rice fish or flowing streams are intended for summer. There are many types of tableware decorated with motifs representing water or running rivers. Use such tableware with together with ice or with place mats in cool colors to create an enjoyable revitalizing ambience.”

“In the same way, tableware depicting momiji maple and ginkgo trees in autumnal foliage are for autumn. This plate looks beautiful when placed so the white drooping element of the design is at the top. Momiji maple motifs are called unkin [clouds and brocade], and many plates and bowls combine both cherry blossoms and momiji. Tableware representing opposing seasons should be rotated, with the cherry portion at the front in spring and the momiji section at the front in autumn. Bowls shaped like plums are best used around January and February. Tableware often feature flower motifs, but you should use them in consideration of when the particular flowers are in season. That way, you can feel the season at your dining table.”

Some tableware may have ordinary-looking shapes, but in fact, they are meant to represent events and express the sensations of the season. “Tableware in the shape of typical New Year’s motifs like a hagoita [badminton-like] paddle or a tsukubane shuttlecock are best displayed in January. There are many dinnerware with plant patterns that have festive meanings for the New Year, such as nanten [nandina], fukujuso [Amur adonis], and shochikubai [an auspicious grouping of pine, bamboo and plum].”

“Diamond-shaped plates and bowls are great to use for Hinamatsuri [Doll Festival on March 3] events. I like to use the plate in the photo in March, the month for Hinamatsuri, because of its pink, white, and green colorings that are reminiscent of hishimochi, diamond-shaped rice cakes. Because it is the shape of a folded paper liner, I use it with the point representing the fold’s crease line at the front. Other tableware decorated with peaches, bonbori paper-shade lanterns, or clams are often used in March.”

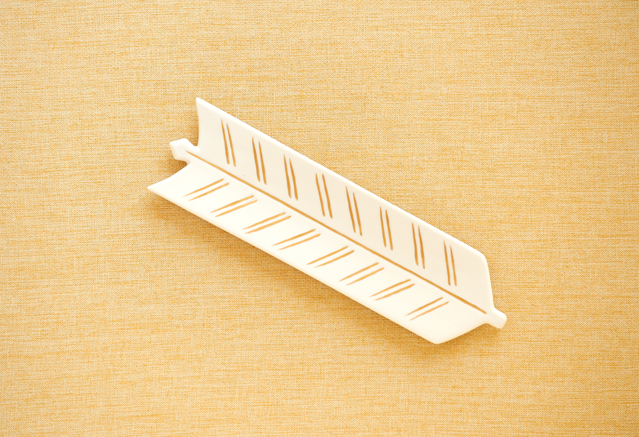

Can you imagine what event this item shaped like arrow feathers symbolizes? “This symbolizes Tango no Sekku [Boys’ Festival] on May 5. Other motifs associated with Tango no Sekku include kabuto helmets, Japanese iris, carp, and oak leaves. When I see one of these dishes or bowls, I can feel that it’s May.”

“This bamboo grass-shaped serving dish can be used throughout the summer, but it is especially well suited for Tanabata [Star Festival] in July. Other Tanabata-themed items I’ve found include tableware inspired by tanzaku paper streamers. In kaiseki cuisine, the food itself is selected with care, but so too are the bowls, plates, and serving dishes. While observing what motifs appear in the tableware and considering what significance the patterns have, you can savor your meal and the world of Japanese cuisine even more.”

You may be able to enjoy the feeling of the season with tableware that are only put out during a particular time at a restaurant, but it’s difficult at home to change your tableware every season. Kubo provides some techniques to evoke a sense of the season with a few small adornments.

“Most households probably use white porcelain on a daily basis. People tend to think that such tableware are easy to use especially from late spring into the summer months. However, depending on how you use them, earthenware plates and bowls can be used as rejuvenating summer tableware too. If you do use earthenware, be sure to moisten them thoroughly with water to make the colors glisten and give them a more refreshing look. Also try using ice or garnishing with something green like green shiso or a bamboo leaf. This will make your dish look that much more cooling and restorative. Green maple leaves are another small item that conveys a summery atmosphere. With tricks like these, you can foster a sense of the season when family or guests come over and take your regular tableware and dining table to a whole new level of lavishness.”

Culinary Researcher

Culinary Researcher

Growing increasingly interested in cooking, Kubo Kanako studied at the long-established Kyoto ryotei (high-class Japanese restaurant) Tankuma Kitamise from the time she was a high school student. After graduating from the Department of English at Doshisha University, she entered the Tsuji Culinary Institute, where she obtained chef’s and fugu (puffer fish) cooking licenses. Following a stint in the Tsuji Culinary Institute’s publications arm, she edited cook books at a publishing house in Tokyo, before going independent.

Today, Kubo is actively involved in a variety of culinary-related endeavors, including culinary production, styling, restaurant menu development, table decorating, editing and more.

She is the author of several works in Japanese, including Utsukushii morituske no kihon [Basics of Beautiful Plating] (Seibido Shuppan), Utsukushii ichiju nisai: “Oishii” to “kirei” in ha wake ga aru [Beautiful Soup and Two Dishes: There are Reasons for “Deliciousness” and “Beauty”] (Kawade Shobo Shinsha), Kichinto, yasai no kobachi chotto shita kotsu de “mō ippin” ga gutto oishikunaru! [Small Vegetable Side Dishes: Little Tips that Make That Extra Something So Much More Delicious] (Kawade Shobo Shinsha), Kichinto, oishii mukashinagara no ryōri [Delicious Old-Time Cooking] and Shun no aji techō aki to fuyu [Seasonal Flavor Handbook: Fall and Winter] (both Seibido Shuppan)

No.1

No.2

No.3

No.4

No.5