Oshima Milk: A Dairy Story of Island Pride and Freshness

Apr 04,2019

Oshima Milk: A Dairy Story of Island Pride and Freshness

Apr 04,2019

Only those quite familiar with the island will know this, but milk from Izu Ohshima is delicious. Indeed, we often heard from people who dislike milk that Oshima Milk is the only brand they can drink. Oshima Milk has a smooth texture that lets you gulp it down, but without any heavy feeling afterwards. Despite its mild taste, Oshima Milk rose out of a pressing food conundrum that once gripped the island and is backed by a strong conviction that has been quietly passed down for generations. The turbulent history of dairy farming, a traditional industry on Izu Ohshima, is packed into every drop of Oshima Milk.

Cows seen leisurely grazing in the pasture in front of Buratto House

When you visit Izu Ohshima, you will often see beloved Oshima Milk, with its retro camellia and Mt. Mihara design, on hotel breakfast tables, at hot springs, in local supermarkets, and in souvenir shops.

You might be surprised that milk is produced on Izu Ohshima, but once you try it, you will be convinced. It has an excellent mouthfeel and light texture. The taste is so light and refreshing that you can imagine calves drinking it up eagerly. It’s no wonder why it’s so popular.

Still, the question nags at you. Why is milk made on Izu Ohshima?

The total area of Izu Ohshima is approximately 91 square kilometers, about 1/24th the size of Metro Tokyo. It’s quite a small island that you can drive around in just over an hour. In the middle of the island stands the majestic Mt. Mihara, which is surrounded by a sea of trees, mirroring how the island itself is encircled by abundant seas. It’s hard to imagine any connection to milk here.

“Izu Ohshima was once called the Holstein island of the East because of its thriving dairy industry. Every household kept dairy cows, and when I was a child, I was in charge of feeding them. Every morning, I would feed the cows before going to school. In my family, we would collect sweet potato vines and corn stalks to make fermented feed, and I got teased sometimes for smelling bad. When that happened, I would retort, ‘It doesn’t stink! It’s a good smell!’ and just shrug them off.”

Shirai Yoshinori, currently the president of Oshima Milk and formerly the chairman of the Ohshima town council

Relating this story is Shirai Yoshinori, the president of Oshima Milk. We asked him why dairy farming was once so prosperous on the island.

“In the Meiji period (1868 to 1912), the tax system changed from paying land taxes to paying monetary taxes. In other words, it went from paying taxes with crops to paying taxes with cash. On remote islands like Izu Ohshima, it was very difficult to earn a stable cash income. That’s why the people turned their attention to livestock farming.”

As times changed and Japanese people began eating more of a Western diet, the demand for meat skyrocketed. As a result, livestock farming became an efficient source of income. Consequently, it became an important industry on Izu Ohshima, which has limited resources, and took root.

“The sea’s presence is important for livestock farming. Cows have high body temperatures and are sensitive to heat. It’s important, therefore, to expose them to the wind to cool their bodies. In this regard, the sea breezes on Izu Ohshima are ideal. Cows, like humans, require salt as a source of minerals. This is why, in the past, it was common to see cows being led to the seaside for a walk. Exposing them to sea breezes and allowing them to graze on fresh vegetation along the shore provided both cooling and mineral supplementation — a two-for-one bonus.”

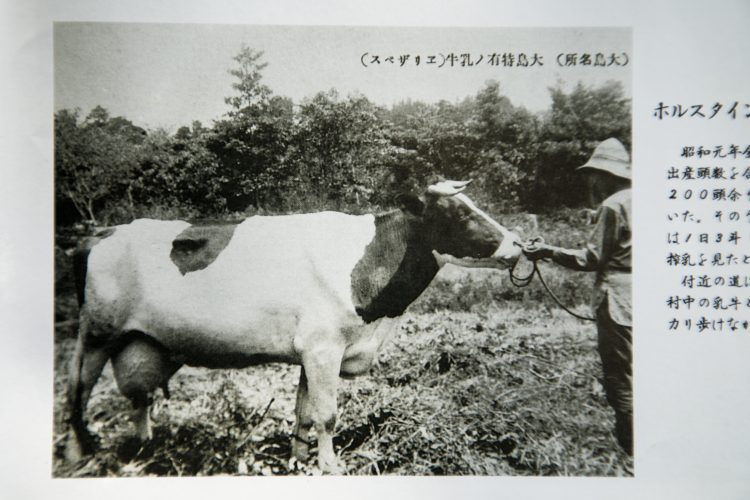

Izu Ohshima was a comfortable place for cows, and it was a common sight to see cows being led along the seaside in the past (Photo taken from the Collection of Nostalgic Izu Ohshima Photographs)

Although cows are herbivores, they are also voracious eaters. With four stomach compartments, they consume enormous amounts of food, eating dozens of kilograms of feed per day. In the past, each household kept several cows, and by 1926, the number of dairy cows on Izu Ohshima had reached an incredible 1,200. Did the cows on Izu Ohshima ever face a shortage of feed?

“Izu Ohshima has a mild climate, so green vegetation is available year round. Cows love plants like tagaya [kassod plants], ashitaba, and Ohshima grass sedge, which are very hardy and reproduce quickly. These plants grew naturally all over the island, so there was never a shortage of feed. From elementary school through to high school graduation, I would go with my parents on weekends and holidays to the mountain with backpacks to gather feed. There were also professional milkers who specialized in milking cows. We would not only take the cows to the milking shed but also sometimes have the milkers come to our home to milk them. That’s how much the cows were cherished.”

As a boy, Shirai would often brush the cows because he thought they were cute and the cows enjoyed it.

Cows thrived on Izu Ohshima, as they were well adapted to the climate and soil. Their manure played a big role in enriching the island’s poor volcanic soil. Thus, cows were not only a vital source of income for families but also contributed to the fertility of the land. This likely greatly benefited crops like sweet potatoes.

Looking after cattle was considered respectable work. Women worked diligently to collect feed for cows, and jobs like milkers were created. Dairy farming was a reliable industry deeply rooted in daily life and the local climate and culture, and one that nearly everyone could participate in.

At the 1921 National Livestock Exposition, Elizabeth, a cow raised by Yoshikawa Mitsuyoshi of Izu Ohshima, was recognized as Japan’s top milk producer, averaging an astonishing 42.84 liters of milk per day over a one-month testing period (Photo taken from the Collection of Nostalgic Izu Ohshima Photographs)

As dairy farming became a major industry supporting Izu Ohshima, products like Oshima Milk and Oshima Butter emerged, while conversations turned to popular souvenirs like milk senbei rice crackers and famous milk baths at hotels. In the early Showa period (1926 to 1989), Izu Ohshima was even referred to as the Island of Milk.

Unfortunately, after overcoming the post-war chaos and raising the surviving dairy cows, and just as farmers were finally seeing a steady increase in herd numbers and setting goals to expand the dairy industry, the times changed dramatically.

“The combined impact of import liberalization and price competition with major manufacturers led to a decline in dairy farming on Ohshima. By 1995, there were only four dairy farms left on the island with only 78 dairy cows…”

If the trend continued, the traditional dairy farming industry of Izu Ohshima would vanish. In response, the town of Ohshima established a municipal dairy farm to promote the breeding of calves. They also began operating a milk processing plant to produce and sell milk and butter. As a result, production reached levels where demand could not be met during the summer, and butter production using surplus milk also recovered in a big way.

In 2007, however, due to a decline in milk consumption and a labor shortage caused by the island’s aging population, the company producing and selling milk and butter faced financial difficulties and went bankrupt. With that, Oshima Milk disappeared from store shelves and school lunches.

“Cows are born on Ohshima, raised on Ohshima plants, give birth to calves, and are a treasure passed down from generation to generation. If they were to ever disappear, they could not be brought back. I was determined to protect dairy farming on Izu Ohshima at any cost. At the time, I had returned to Ohshima and was serving as an Ohshima town councilor, even holding the position of chairman for a time. People from the island kept coming to me asking me to do something. The nutritionist in charge of school lunches left a particularly strong impression on me.”

“Children don’t finish their milk anymore because it tastes different from Oshima Milk. I want the children to keep on drinking safe, delicious Oshima Milk. Oshima Milk is the real deal. I want the children to know the real taste of milk. Do what you can to make sure Oshima Milk doesn’t disappear from school lunches.”

The nutritionist apparently visited Shirai repeatedly, imploring him with arguments like those above to continue Oshima Milk. Memories of food are etched into the body and soul. The nutritionist’s desire to teach children through food resonated with Shirai.

“In the spring of 2008, about 190 volunteers gathered to form the Oshima Milk Lovers’ Club and launched a campaign to revive Oshima Milk and Oshima Butter, while also establishing Oshima Milk Co., Ltd. I urged the other council members, saying ‘We must do this even if it means operating at a loss.’ The then-chairman, Fujii Shizuo, who understood the island’s zeal, made the decision to continue the production of Oshima Milk. He said at the time, ‘We must not let Ohshima’s milk disappear! The town council is fully behind this.’”

Shirai’s words bring back the passion of that time and speak to how significant dairy farming is to Ohshima.

After leaving his town councilor post, Shirai became the president of Oshima Milk Co., Ltd. and has continued to dedicate himself to preserving and developing Oshima Milk. In response to requests from teachers who transferred to the neighboring island of Toshima and nutritionists responsible for school lunches on the island, he arranged for Oshima Milk to be delivered to Toshima, developed Oshima Milk Ice Cream, and actively participated in food-related events. In ways like these, he has championed Oshima Milk.

“It’s my way of giving back for my time as a councilor,” Shirai says casually, but it’s impossible not to sense the significant resolve and responsibility he carries. The desire to carry the island’s history forward and pass it on to the next generation still burns fiercely within him, even at the age of 75.

Oshima Milk is produced by a surprisingly small number of people. In general, one person takes care of the cows and milks them, three to four people work on the milk production line, and one person makes the ice cream. On days when there is a large amount of milk, butter is also produced, so Shirai joins in, taking turns to rest while working every day.

“When Mt. Mihara erupted and the entire island was evacuated, the firefighters who stayed behind fed and cared for the cows, protecting them. We can’t just abandon these cows and their milk just because circumstances change. But to be honest, we’re currently struggling to keep things going because we don’t have enough people.”

Matsuda Seiichi is the only person who looks after the cows. The cows eat and relax in the pasture, and when it’s time for milking, they line up at Matsuda’s call and head to the milking shed. During milking, should the cows become nervous, Matsuda will speak to them gently, like a cow whisperer.

Both the cows and their milk are living organisms. To keep the production line sterile, the parts are removed and disinfected until they shine. This single task takes over an hour to complete.

Oshima Milk Ice Cream also has a mild flavor. “In summer, many people eat up two cups in one go,” says Shirai. He is particular about filling the cups without leaving any air pockets.

The staff members on milk production duty on the day of our interview. From the left: Takahashi Shunji, Kasama Noboru, factory manager Oikawa Eizo, and president Shirai Yoshinori.

Izu Ohshima is home to many food cultures that have been preserved and passed down for decades. In this series, we have featured natural sea salt, kusaya (salted, fermented, and dried fish noted for its pungency), bekkou sushi, sweet potatoes, camellia oil, ashitaba, and milk. The rapid post-war changes in lifestyles, and the resulting Westernization and simplification of diets, were a massive wave that swept over Japan. This wave could have instantly swallowed up such food cultures that arose from the land and lifestyles, transforming them into something completely different or even causing them to disappear.

Despite this, Izu Ohshima’s food cultures have been passed down successfully, largely unchanged. What has sustained these food cultures is the unwavering belief and remarkable integrity of their producers.

Shirai’s words still echo in our minds. “It’s not about the surface. What people need to really understand is the unchanging essence at the root. That is what I believe to be the treasure of Izu Ohshima.”

From the left: Oshima Milk, Oshima Butter, and Oshima Milk Ice Cream. All are sold exclusively on the island. The ever-popular butter has the mild flavor characteristics of Oshima Milk, a taste you can enjoy every day. Buratto House, in front of the pasture, sells gelato made using Oshima Milk. The gelato is very popular among the locals.

*Oshima Milk products are available for purchase from Buratto House and other outlets on the island.

●Getting to Izu Ohshima

Getting to Izu Ohshima takes an hour and 45 minutes by high-speed jet ferry or six hours by overnight ferry from Tokyo’s Takeshiba Sanbashi Pier. There are also ferry services from Yokohama Port and Kurihama Port in Kanagawa and Atami Port and Ito Port in Shizuoka.

Contact Tokai Kisen at 03-5472-9999 or 0570-005710

URL:https://www.tokaikisen.co.jp/