Lẩu Mắm: Bold Vietnamese Fermented Hot Pot Flavor

May 13,2021

Lẩu Mắm: Bold Vietnamese Fermented Hot Pot Flavor

May 13,2021

Vietnamese cuisine is famous for pho, fresh spring rolls, and nuoc mam fish sauce. But there are many other Vietnamese foods and fermented seasonings that are still little known here in Japan.

To learn more about Vietnam’s diverse culinary culture and what makes it so special, we talked with Vietnamese food expert Ito Shinobu, who runs An Com cooking school.

Even since she can remember, Shinobu has always loved cooking. When she was in high school, she would even prepare her own bento every day.

“The bento lunches my mother made for me all looked dull and brown, so I decided to make my own. I would add extra colors and get creative prepping the ingredients. It fascinated me how cooking transformed the ingredients. I was incredibly curious about food.”

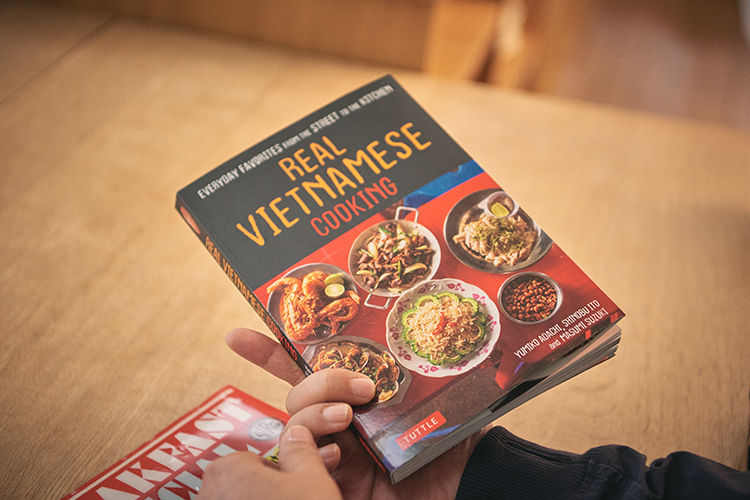

Some of the books that Vietnamese food expert Ito Shinobu has had a hand in

After graduating from college in home economics, Shinobu worked as an assistant at a major cooking school; then, while still in her twenties, she led a busy life as a food coordinator. She was planning a trip to Asia to get a break from it all, when she came across the book that would determine the course of her life.

“I read a guidebook called Vietnam Sentimental by photographer Fukui Takaya, which made me decide to travel to Vietnam. My heart was set on eating the kind of Vietnamese food featured in the book. An awful lot of people I knew back then who got into Vietnam thanks to that book.”

Later, in Vietnam, Shinobu happened to become acquainted with Fukui Takaya, the author of Vietnam Sentimental, and the two immediately hit it off. They became so close that he coauthored her first book. It was truly a friendship meant to be.

When staying in Ho Chi Minh City, Shinobu attended a Vietnamese cooking school that accepted tourists visiting from Japan. She was astonished by the food preparation techniques she learned there.

“I’d studied culinary arts at school and applied that knowledge on the job. Well, Vietnamese cuisine turned everything I thought I knew about food on its head. I was completely blown away. For example, when making nimono (simmered food) in Japan, you add sugar, salt, vinegar, and other seasonings in a fixed order while simmering the liquid so it slowly thickens. That’s just the way it’s done. But in Vietnamese cooking, first you soak the ingredients in a thick liquid made by combining nuoc mam, sugar, and caramel (boiled-down coconut water). Then you simmer the liquid while diluting it. The experience was one eye-opener after another.”

Mam sold at the market. This fermented seasoning plays a key role in Vietnamese cuisine.

When asked why she found Vietnamese cuisine so appealing, Shinobu cited the Vietnamese word phong phu. Cognate with Japanese hōfu or “abundant,” it means “plentiful” or “diverse.” The appeal of Vietnamese cuisine is that it’s phong phu.

“The more you get to know Vietnamese food, the more new dishes you come across. Vietnamese food has been influenced by China, which once ruled the country, and colonial France. It’s also heavily influenced by the ethnic Chinese who arrived after independence. Vietnam has fifty-four ethnic groups, and they each have their own culturally distinctive cuisines. There are minorities in the north and the Cham in the central and southern parts of the country, as well as the Khmer, a Southeast Asian people who mainly inhabit Cambodia. So you start wanting to learn about their history and ethnography as well. The deeper you delve into Vietnamese food, the more you realize it’s an endless quagmire.”

Some of Shinobu’s Vietnamese tableware, which she’s spent decades collecting. They highlight the food with their simple design.

Part of the magic of Vietnamese cuisine is the concept of five flavors, five colors, and two aroma characteristics. The five flavors are salty, sour, sweet, spicy, and full-bodied. The five colors are black, red, blue (or green), white, and yellow. The two aroma characteristics are pleasant-smelling and fragrant. The five flavors and five colors are both time-honored concepts, but the idea of there being two aroma characteristics is one that recently caught on in Japan after Shinobu herself propounded it.

“Vietnamese cuisine isn’t just about how pleasant-smelling ingredients like herbs and citruses are in themselves. It’s also about the fragrance imparted during the preparation process, such as deep-frying garlic in oil, for example, or caramelizing it. Pepper is added during cooking, then sprinkled on again at the end as a finishing touch to create a fresher aroma. In Vietnam itself they talk simply of ‘aroma,’ but then it occurred to me there were two such qualities, which I termed the ‘two aroma characteristics.’”

One attractive feature of Vietnamese cuisine that anyone Japanese will certainly appreciate is the central role of rice. The name of Shinobu’s cooking school, An Com, means literally “eat rice” or “have a meal.” An means “eat” and com means “rice.”

“In Vietnam, rice is eaten mainly at lunch and dinner. Noodle dishes like pho, as well as banh mi, are generally thought of as breakfast foods or afternoon or late-night snacks. So the only Vietnamese food that you see in Japan is snack food. Dishes that go well with rice don’t get much exposure here — yet the fact is, they come in the most varieties.”

Another wonderful thing about Vietnamese cuisine is its sheer variety of fermented seasonings. The fish sauce nuoc mam is well known in Japan, but there also are many other fermented seasonings unique to Vietnam.

Mẻ is a thick white liquid seasoning from northern Vietnam. The best way to describe it might be this. It’s like the sweet Japanese rice beverage amazake, only without the sweetness. It’s more fermented so that it tastes sour. As an example of how it’s used, a little is added to plain-tasting fish broth to enrich the flavor.

Mẻ, a fermented seasoning from northern Vietnam, is also available bottled. It’s like a sour version of the sweet rice beverage amazake.

Vietnamese cuisine is so closely associated with fish sauce that it seldom brings to mind soybean paste. But in fact Vietnamese soybean paste, called tuong, comes in many regional varieties. In the north, tuong takes the form of a watery paste made by fermenting ground soybeans, corn flour, and sticky rice flour together. It’s used for making simmered dishes and as a sauce.

Tuong, or Vietnamese soybean paste. In the north, it typically takes the form of a liquid.

So of all the Vietnamese fermented seasonings out there, which is Shinobu’s favorite? And what’s her favorite dish made with it? We asked her.

“I love mam ca, which comes from the Mekong delta in the south, and lau mam, the hotpot made with it. I’m not a mayo addict; I’m a mam addict [laughs].”

Mam ca is a fermented seasoning made by salting fish, then pickling it in nuoc mam. Mam means “fermented seafood.” Ca means “fish.”

Lau mam is a type of hotpot made with a soup base infused with generous amounts of mam ca. The soup is also flavored with lemongrass, ginger, and pork belly, plus sugar for sweetness. To this are added fish and shellfish like prawns and swamp eels, along with plenty of vegetables. It’s a profound taste experience.

The fermented hotpot lau mam, a specialty of the Mekong delta

“It’s not that a little mam is used as a seasoning or dip; the soup itself tastes intensely of mam. It’s literally mam galore. It’s a thick soup combining the salty taste of mam with the sweet taste of sugar. Another nice thing about it: it’s a great way to get plenty of vegetables.

“When I tell Vietnamese people that I love lau mam, they’re just delighted and are happy to be interviewed. I suppose it’s similar to how we in Japan are delightfully surprised when a foreigner says they love natto (fermented soybeans).”

Mam ca linh, made with a type of fish called linh. It’s used in lau mam.

In 2021, an English translation of a book Shinobu coauthored with Adachi Yumiko and Suzuki Masumi appeared under the title Real Vietnamese Cooking. (The original Japanese book was entitled “Vietnamese Cuisine Isn’t Just Fresh Spring Rolls.”) It’s not every day that a Japanese book about Vietnamese food gets translated into English for a global audience.

Real Vietnamese Cooking, an English translation for a global audience

Vietnamese cuisine is still largely unknown in Japan, but Shinobu is an expert guide. Asked about her plans for the future, she replies, “I want to make more people aware of all that Vietnam has to offer in the way of food.”

Vietnamese food expert

Vietnamese food expert

Ito Shinobu’s career as a Vietnamese food expert began upon her return to Japan from Ho Chi Minh City. She currently runs An Com cooking school in Tokyo’s Shibuya Ward. She appears in cooking shows on TV and provides recipes for magazines. She is also author or coauthor of numerous books on Vietnamese food, including A Food Tour of Vietnam and The Vietnamese Moms’ Cookbook (both in Japanese). She is highly active on the Vietnamese food scene.

Vietnamese Cooking School An Com(Japanese only)