Malaysian Cuisine: Multi-ethnic Flavors and Fermentation

Jul 01,2021

Malaysian Cuisine: Multi-ethnic Flavors and Fermentation

Jul 01,2021

Malaysia is home to many ethnic groups. The country’s cuisine, reflecting as it does their different food cultures, is a study in diversity. One person who has fallen in love with Malaysian cuisine is Furukawa Oto, who brings it to a Japanese audience by holding cooking classes and distributing a free magazine. We asked her about Malaysia’s cuisine and fermented foods.

Oto originally worked as an interviewer and writer at an editorial services provider. Then her husband was transferred to Malaysia, which proved a turning point in her life. After the couple moved to the Malaysian capital, Kuala Lumpur, in 2005, she decided she wanted to continue reporting and writing. She therefore started working at a company that published a free newspaper for the local Japanese community.

“I had no particular interest in Malaysia until then. But after living in the country for a while and working with Malaysians, I grew extremely fond of Malaysian society’s unique makeup.”

Furukawa Oto, head of Malaysia Gohan Kai

Besides the three main ethnic groups — Malay, Chinese, and Indian — there are the Peranakan, the mixed-race descendants of Chinese immigrants and local Malay women. There are the descendants of European settlers. And there are many indigenous peoples. Oto says that she fell in love with the air of openness and freedom created this diverse population with their different religions and cultures.

“Initially, I was shocked at how the mindset differed completely from that in Japan. For example, a lot of my colleagues were ethnic Chinese, and they would speak in Chinese at lunchtime. Often, I didn’t understand a thing that was going on. Japanese people in the same situation would probably go out of their way to speak in English so everyone understood what was being said. But being overly considerate of others can sometimes make things awkward. There are times when you feel more at ease when people aren’t falling over themselves to accommodate you. The way Malaysians just let things take care of themselves really suited my style.”

As Oto got to know her colleagues better, she realized that even among themselves, they were a surprisingly diverse bunch. They didn’t all share the same linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Their native tongues differed: for some it was Cantonese, for others Fujianese. Even in the market, the food stalls were discreetly arranged to accommodate religious differences, so that Muslim Malays, who don’t eat pork, and non-Muslims could rub along in the same space.

Nasi lemak, the national dish of Malaysia. The red stuff in the small glass (foreground) is sambal.

“In Japan, there’s a strong tendency to think it’s better to be like everyone else, but in Malaysia, being different is the norm. Respecting each other’s differences is fundamental to the culture. It’s a very Malaysian quality, and nowhere does it display itself more than in the country’s food culture. Nasi lemak, the national dish of Malaysia, symbolizes that.”

Nasi lemak consists of rice cooked in coconut milk and served with sambal (chili pepper paste), ikan bilis (dried anchovies), cucumber, peanuts, eggs, and other ingredients.

Ethnic Malays, Chinese, and Indians in Malaysia each have their own distinctive culinary cultures with separate foods, but the one thing that all three eat is nasi lemak. As Oto puts it, mixing the rice with the other ingredients as you eat epitomizes Malaysian culture with its blend of different ethnicities.

On returning to Japan in 2009, Oto was eager to spread the word about Malaysia’s diverse food culture. She therefore banded together with like-minded friends who had lived in Malaysia to form a group called Malaysia Gohan Kai (“the Malaysian Food Association”). Starting in 2016, this group organized an event called the Malaysia Makan Fest, which brought Malaysian food and culture to Japanese fans. It was held for four years running.

“We did all the organizing ourselves, and the staff were all volunteers. At the outset, we figured we’d be doing all right if we didn’t end up in the red, but in the very first year, the turnout far exceeded our expectations. The venue opened at ten o’clock, and by eleven all five Malaysian food booths were completely sold out. We had to rush back and forth preparing food at a nearby restaurant and bringing it to the site. It was a frenetic start, but it made me realize how many lovers of Malaysian culture there are in Japan. We got real traction.”

The Malaysia Makan Fest could never have happened without the help of Malaysian chefs living in Japan, says Oto. One of them is Cheah Kaishin, owner of Malay Asian Cuisine (pictured).

The Malaysian cooking classes given by chefs making waves at Malaysian restaurants in Japan were also a big draw, and many students signed up for them.

“Unfortunately, it’s been difficult to hold in-person cooking classes since Covid came along, so now we’ve gone online. For example, we connect online with a cooking instructor living in Penang, Malaysia. They demonstrate how to make a meal while taking us on a virtual tour of their home and kitchen. It’s neat to be able to communicate this easily with people in other countries. That was a new discovery for me.”

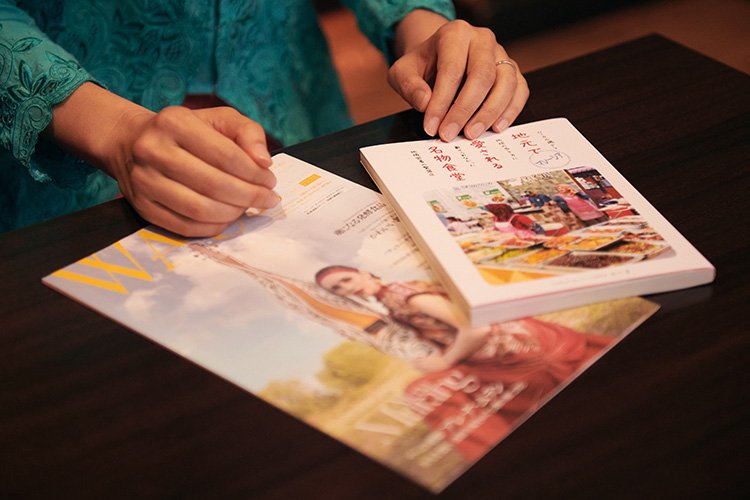

The free magazine Wau, published quarterly, and Oto’s book Celebrated Malaysian Eateries Loved by the Locals

The free magazine Wau, which Oto puts together with other writers and designers who share her passion for Malaysia, takes readers on a deep dive into Malaysian culture. It has come out quarterly since being launched in 2014. Issue No. 28, which appeared in June 2021, includes a feature on Malaysian fermented food.

“Actually, I’m really into fermentation these days. One of the hallmarks of Malaysian fermented foods, like those of neighboring Asian countries, is the abundance of fermented seasonings made from seafood like fish and shrimp. And the meals made with those seasonings all center on rice. Japan likewise has a food culture revolving around rice, so by extension I’ve become interested in Japanese fermented foods as well.”

One of Malaysia’s signature fermented foods is belacan, a fermented shrimp paste sometimes used to make the sambal accompanying nasi lemak. Besides sambal, it’s also used in many other Malaysian foods.

Sun-drying belacan in Penang

“One of the most common Malaysian dishes is kangkung belacan, or water spinach stir-fried with shrimp paste. I suppose it’s something like spinach ohitashi in Japan.”

Kangkung belacan: water spinach stir-fried with shrimp paste

Then there’s ikan masin, which is made by salting and fermenting fish, then drying it in the sun. It’s the same as the Cantonese salted fish used in Chinese cooking. It comes in two varieties, one well fermented and soft, the other lightly fermented and with a tougher texture. Each has its own uses.

“Ethnic Chinese often use the softer variety. The tougher variety is often used for seasoning nasi goreng and stir-fried vegetable dishes.”

Ikan masin hanging in the market

In addition, Malaysian fermented seafood seasonings vary by region. In the northern part of the Malay Peninsula, there’s a thick, cloudy fish sauce called budu. In the state of Malacca, there’s cincalok — small shrimps or krill lacto-fermented with salt and rice. In Kedah and Perak, there’s pekasam ikan, which is made by coating fish in salt and toasted rice grains, then fermenting it.

One fermented food seldom encountered outside Malaysia is tempoyak. This is made by adding salt to durian — the king of fruits, which people either love or hate — and fermenting it. Oto tried making her own batch at home.

“There are different grades of durian, and tempoyak is usually made with the cheapest variety. But since I was going to make it anyway, I tried making it with a high-end brand called Musang King. When I fermented it, it ended up having a mild taste, with little of the powerful odor typical of durian. Fermenting it gave it an acidic quality, making it taste like mango. It was tangy on the tongue and tasted delicious even eaten as it was.”

The tempoyak (fermented durian) Oto made herself using Musang King

Tempoyak is used in stewed fish dishes. It’s also mixed into sambal or budu as a seasoning. It’s produced in large amounts in Pahang and on the island of Borneo, where durian is grown. Tempoyak apparently originated when some leftover overripe durian was placed in storage. Seafood restaurants that use it in their food are a popular destination in Kuala Lumpur nowadays.

“I plan to continue sharing Malaysian food culture in ways that only I can,” says Oto. Lately, she’s turned her attention to cultural anthropology as a means of better understanding Malaysia’s multicultural makeup. Stay tuned for her latest insights into this fascinating country.

After spending four years in Malaysia, Furukawa Oto formed Malaysia Gohan Kai (“the Malaysian Food Association”). She’s been working to bring Malaysian cuisine to a Japanese audience ever since. She organizes events and cooking classes, publishes a free magazine, and writes extensively about Malaysian food. She is the author of Nasi Lemak! and Malaysia Cookbook: Nasi Lemak to Chicken Rice (both published by Malaysia Gohan Kai) and Celebrated Malaysian Eateries Loved by the Locals (published by Gakken Plus).

No.1

No.2

No.3

No.4

No.5