Hinamatsuri: The Evolution of Japan’s Doll Festival

Mar 02,2023

Hinamatsuri: The Evolution of Japan’s Doll Festival

Mar 02,2023

March 3 is the day of the Joshi Festival, also known as the Peach Festival or Doll Festival. Many Japanese mark the occasion by displaying traditional dolls and eating chirashizushi—rice topped with raw fish and vegetables. So when did the Joshi Festival originate? How did it assume its present form? We ask food culture expert Kiyoshi Aya.

March 3, the day of the Doll Festival, is originally the Joshi Festival, one of the five traditional seasonal festivals. The five seasonal festivals come from ancient China, where dates repeating the same odd number were considered inauspicious.

“Since olden times,” Aya explains, “various rituals to expel evil spirits have taken place on the seventh day of the first month, the third day of the third month, the fifth day of the fifth month, the seventh day of the seventh month, and the ninth day of the ninth month. The present custom of eating rice porridge made with seven herbs on January 7 and that of displaying a warrior’s helmet on May 5 both evolved from such apotropaic rituals.”

Food culture expert Kiyoshi Aya

The custom of celebrating the five seasonal festivals reached Japan from China in the Heian period (794-1185). It first caught on among the nobility.

“In Japan, it was customary to exorcise evil influences by rubbing one’s body with an effigy made of paper to transfer impurities to it, then discard the effigy in a river. This form of exorcism came to be performed on the day of the Joshi Festival—the third day of the third month—as well. In addition, there was the courtly custom of holding what were called ‘winding-stream banquets’ on this day. The rule was that you had to compose a poem before a cup of sake floating downstream passed by you. This party game was highly popular among the nobility.”

In the Heian period paper effigies were used, but over time the paper was replaced by cloth and the effigies came to be stuffed, until they evolved into the elaborate dolls we now know. Even today in places like Tottori and Wakayama, dolls are set adrift on the river to avert disease in a practice reminiscent of the apotropaic rituals of old.

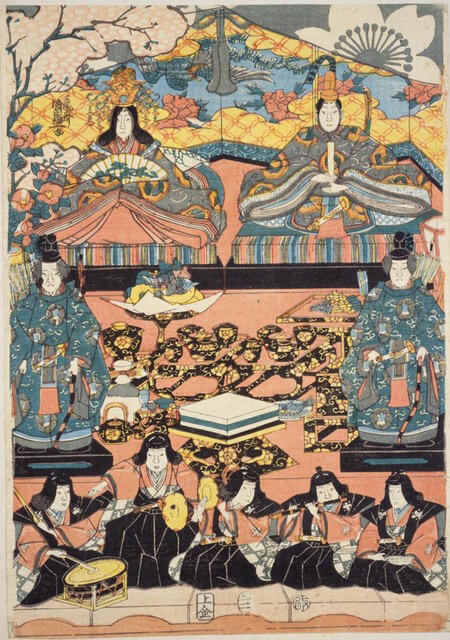

A beautiful display of dolls for the Doll Festival, from Hina ningyō (1857).

Note also the three lozenge-shaped rice cakes—white, green, and white—stacked one on the other. Source: National Diet Library Digital Collections.

Splendid multi-tiered displays of dolls didn’t appear until the latter half of the Edo period (1603-1867).

“In the Edo period, the Tango festival was considered an occasion to celebrate boys’ growth and pray for their health, and the custom spread of displaying warrior dolls and flying carp streamers on that day. The Joshi Festival, meanwhile, came to be called the girl’s festival. In the 1800s, during the later Edo period, dolls markets were held in the runup to the occasion. But it wasn’t until the Meiji period (1868-1912) that elaborate, multi-tiered doll displays became common in ordinary homes.”

Elaborate, multi-tiered doll displays became common in the Meiji period. Illustration from Tōkyō fūzokushi (1901).

Source: National Diet Library Digital Collections.

So why did the Joshi Festival come to be known as the Peach Festival? It was believed that drinking peach wine—sake with floating peach blossoms—on this day averted disaster and warded off disease. The ancient Chinese prized the peach as a sacred tree that drove off evil, prevented calamity, and brought longevity. Hence the Heian nobility were fond of drinking peach wine on the third day of the third month.

The present custom of drinking shirozake or sweet white sake didn’t emerge until to the Edo period, Aya explains.

“In the Edo period, there was a sake dealer in Kamakuracho, Tokyo , called Toshimaya. As the Joshi Festival approached, this place would sell shirozake. The drink became all the rage among the common people, as can be seen from contemporary sources. Shirozake is made by fermenting sticky rice and rice koji in mirin (sweetened sake). One theory holds that it was invented because sake tended to be in short supply at the end of the second month, when rough seas often disrupted shipping.”

Later, the custom emerged of drinking amazake on the Doll Festival. Amazake is a sweet white beverage like shirozake, only it’s non-alcoholic, so children can drink it too.

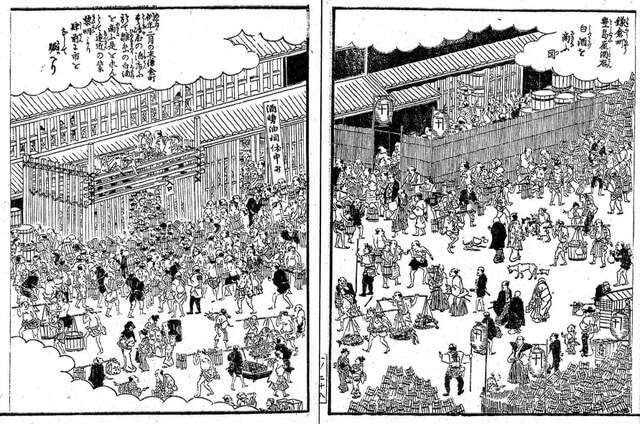

A bustling scene at the sake dealer Toshimaya, vendor of shirozake. Illustration from Edo meisho zue (1834-36).

Source: National Diet Library Digital Collections.

It’s also customary to eat hishi-mochi or lozenge-shaped rice cakes on the Doll Festival. These first appeared at the beginning of the Edo period. Previously it had been common practice to eat a green rice cake called kusamochi to tap the rejuvenating power of fresh greenery. In the Heian period, kusamochi consisted of rice balls to which were added cudweed, one of the Seven Herbs of Spring. From the beginning of the Edo period, kusamochi made with mugwort became the norm. The stack of three lozenge-shaped hishi-mochi familiar today appeared in the second half of the Edo period.

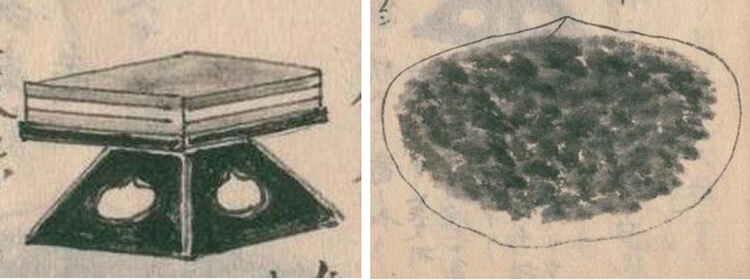

Illustrations of two types of Doll Festival cakes, lozenge-shaped hishi-mochi (left) and itadaki, from Morisada mankō (1837).

Source: National Diet Library Digital Collections.

“There are various theories as to why hishi-mochi are lozenge-shaped. They represent the heart, it’s said. They represent an arrowhead repelling evil. Or they assumed that shape because the lozenge symbolized womanhood in yin-yang philosophy. In the Edo period, the three stacked cakes were typically green, white, and green. The green, white, and pink combination you see today emerged in the Meiji period. There were also many regional variations. In Wakayama Prefecture, yellow, white, and green hishi-mochi were to be seen. In Imabari, Ehime Prefecture, lozenge-shaped rice cakes were placed atop large round rice cakes called kagami-mochi and decorated with sprigs of peach. In Kyoto, a confection called itadaki (akoya or hichigiri) was displayed.”

Festive sushi rolls from Kamogawa, Chiba Prefecture

In many Japanese homes, a type of sweet rice cracker called hina-arare is eaten on the Doll Festival, and clam soup is served. Such traditional festive foods vary from region to region and era to era, Aya notes.

“Shellfish have been eaten on the Joshi Festival since olden times. After all, this is traditionally the season when people in Japan head to the beach to dig for shellfish. It was also once customary to go to the river or ocean to rid oneself of evil spirits. The types of shellfish gathered on this occasion varied considerably depending on the region. Besides regular clams, they included asari clams, turban shells, and pond snails. In one region, pond snails were served in vinegared miso.”

The custom of gathering shellfish gradually became associated with the game of shell-matching popular among the aristocracy. Thus clam soup became a staple of the festival. As for hina-arare, it was already being eaten in the Edo period.

“Hina-arare comes in many different regional varieties. Typically, it takes the form of bite-sized pellets in the Kansai region and sweetened puffed rice in the Kanto. In Ehime Prefecture, there’s a confection called hina-mame or ‘doll beans,’ which consists of puffed rice with peanuts. It resembles okoshi, a type of sweet rice cracker. Other well-known doll festival confections include karasumi from Gifu Prefecture, which resembles uiro, a type of sweet rice cake, and okoshigata from the island of Sado in Niigata Prefecture.”

Okoshigata, a Doll Festival confection from the island of Sado in Niigata

Today, people celebrate the Doll Festival by making a brightly colored batch of chirashizushi, say, or sushi rolls with elaborate designs, both of which are suggestive of spring. Or maybe they’ll line up a cake for the occasion.

“Like the other four seasonal festivals, the Joshi festival has undergone many changes over the centuries. Now it’s an established part of Japanese life. So don’t worry too much about how it’s traditionally celebrated or what foods are traditionally served. Just spend the day enjoying the coming of a new season.”

Food culture expert

Food culture expert

Kiyoshi Aya is an expert in food culture history, traditional festive foods, and local cuisine. She is the coauthor of Washoku Notebook and Hometown Foods (both published by Shibunkaku) and the author of Food Atlas (published by Teikoku Shoin). Her most recent book is Enjoy the Taste of Japan with Seasonal Foods 366 Days a Year: An Illustrated Guide (Tankosha Publishing). She is Secretary of the Washoku Association of Japan. She also serves as a member of various food culture projects run by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and the Japan Tourism Agency.