The area around Nagano Station has long thrived as the center of the city of Nagano. On the west side is the town that grew up around the great Buddhist Zenkoji temple, a designated National Treasure. The east side is lined with office buildings, restaurants, and bars. A little beyond the hustle and bustle around the station, a ten-minute walk from the east exit, is the city’s Wakasato district. It’s a quiet residential neighborhood dotted with facilities like a cultural center, a library, and medical clinics. Tucked away here is Murata Shoten, a producer of natto or fermented soybeans. Over the doorway of the retail outlet next to the factory, a noren split curtain sways in the breeze, emblazoned with the words, “Founded in the Twenty-sixth Year of Showa” — 1951. The name Murata Shoten is sure to come up in any discussion of Nagano’s best natto. It’s a family-owned maker of natto well known to the cognoscenti. We talked to its third and current president, Murata Shigeru.

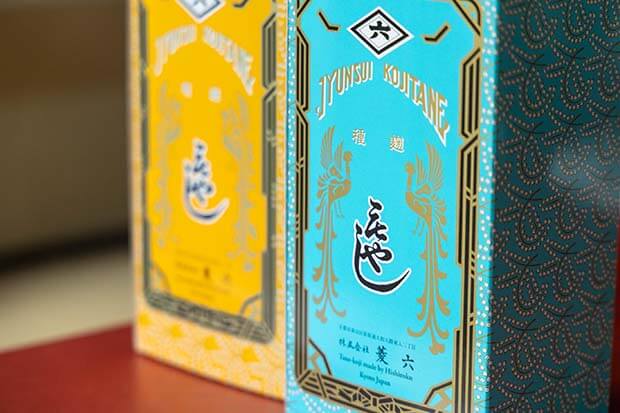

Natto wrapped in paper-thin sheets of wood — that great traditional Japanese packaging material

Murata Shigeru, the third and current president of Murata Shoten, greeted our reporting team with a big smile. “Right now, we’re wrapping Kokin Natto in kyogi” — wood shaved into paper-thin sheets. “Would you like a tour of the factory?” We immediately donned white coats and stepped inside. Surprisingly, the factory didn’t smell of natto; a sweet aroma wafted through the air. The employees were grouped in one spot working diligently away. They ladled steamed soybeans into sheets of kyogi. They then adroitly folded the sheets into triangular blocks of natto. The natto bacillus, Bacillus subtilis var. natto, had already been mixed into the beans. We sampled the steamed soybeans. They were still warm and tasted delicious, with a trace of sweetness. And the kyogi natto wrappers had character. These thin sheets of shaven wood were once used in Japan for wrapping all manner of foods: fish, meat, dumplings, onigiri rice cakes. Today, though, they’re seldom seen anymore.

“Natto wrapped in kyogi sheets isn’t just aesthetically pleasing. The sheets also keep humidity at the right level and, thanks to pine resin’s antibacterial properties, are very hygienic. What’s more, they’re permeable to oxygen, allowing the natto bacillus spores to multiply, resulting in a stringier, stickier consistency. And they eliminate the ammonia-like smell peculiar to natto.

“The kyogi sheets we use here are produced in Ina, Nagano Prefecture. They’re made from Japanese red pine. A craftsman makes them by hand, shaving off one sheet at a time. But there are barely ten kyogi makers left in the entire country. The person we used to ask to do the job was the only kyogi maker in Nagano, but four years ago they greatly cut back on their workload because they were getting old. That really put us in a bind. Then one day I came across an article in the local newspaper about how a woodworking firm in Ina had acquired a machine from that person and started making kyogi itself. That immediately made me sit up, as Ina is a producer of red pine. I headed straight there and placed an order.”

Filling sheets of kyogi with steamed soybeans. Freshly steamed soybeans are brown, but their surface turns white about ten hours after fermentation begins. The natto bacillus itself has no color or odor. The smell and sticky white strands characteristic of natto develop during the fermentation process.

Each portion of Kokin Natto contains a fairly generous eighty grams. About 1,400 portions are packed in kyogi sheets in about two hours. The triangular blocks are loaded one by one into cases.

“These cases are stacked and placed in the fermentation room at a temperature of 41–42˚C. They’re left to ferment for about 18 hours, and then the natto is ready. Then comes the packaging. Natto wrapped in kyogi has a fixed shape, so no adhesive is used. It’s simply placed in a triangular sheet of outer film.”

Here are the stages in the natto-making process: Wash the soybeans. → Soak overnight. → Steam in a pressure cooker. → Spray on natto bacillus. → Place in containers. → Ferment. → Package. → Ship.

Natto is typically packaged in styrofoam containers, and the production process itself is basically the same everywhere. One characteristic of the natto production process is that the container itself doubles as a fermenting vessel. The sole ingredients are soybeans and natto bacillus; no flavoring is required. A fermented food couldn’t be simpler. But that being the case, how does a natto producer distinguish itself from the competition? I threw that question at Shigeru. His answer was unequivocal.

“The key to making great-tasting natto is being a stickler about the soybeans you use.”

Left: Natto in kyogi sheets prior to fermenting.

Right: A freshly opened package of well-fermented Kokin Natto. Having absorbed plenty of oxygen, it’s moist yet elastic and forms long, sticky strands when mixed.

Mass-produced natto, price wars, and the existential threat of 100 yen three-packs

Murata Shoten was founded in 1951, not long after the end of World War II. It was started by Shigeru’s grandfather Murata Hyoe, a native of Sendai. When Hyoe returned from the war, he learned the art of natto making from his brother, who had run a natto place called Masaoka Natto at the family home in Sendai since before the war. Aspiring natto makers looked up to this brother as a mentor, and ten apprentices studied under him. After their apprenticeship, they dispersed all over the country to pursue their own careers. Among them was the proprietor of Takahashi Shokuhin Kogyo in Kyoto Prefecture, renowned for Tsurunoko Natto.

“My grandfather moved here after apprenticing with his brother because there was a factory vacant. At first, he gathered what were called aze-mame or ‘ridge beans’ for making natto; these were beans sown on the ridges between rice paddies to make home-made miso. Later, when imported soybeans from China became available, he started used those. They were called Chukyo beans, and I’m told that they were of very high quality. The first product he made was called Issa Natto. The name was inspired by Kobayashi Issa, a haiku poet of the Edo period (1603–1867) from Nagano, and his famous haiku

Skinny frog,

Don’t give in. Issa

Is right here.

Issa Natto proved very popular locally. The more the company made, the more it sold — so much so that even today, many people still refer to us not as Murata Shoten but as Issa Natto. It’s become our trade name.”

The determination of Shigeru’s grandfather Hyoe to prevail against the odds is evident from his fondness for this haiku — an exhortation to an emaciated frog with which the poet himself identifies.

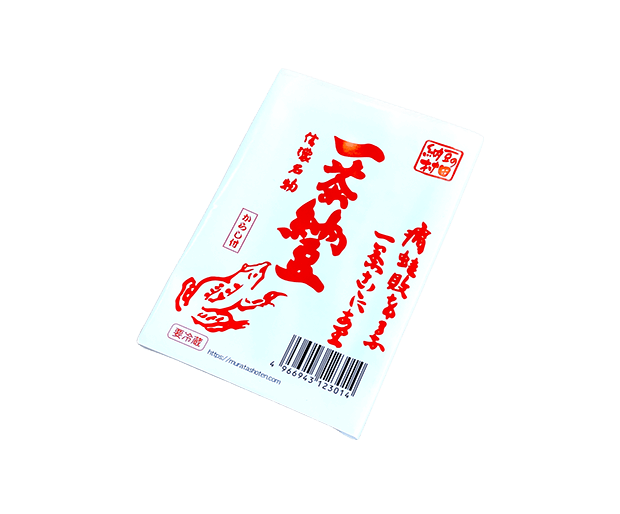

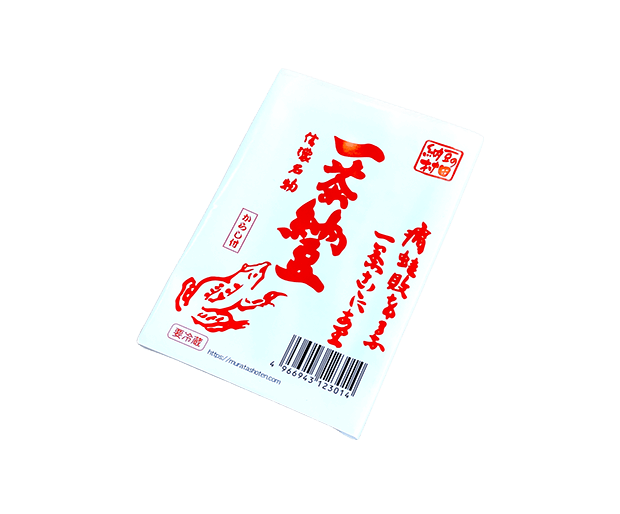

Left: Issa Natto, Murata Shoten’s debut product. The frog design and lettering by a calligrapher who was an acquaintance of the founder retain their vibrancy over seventy years later. This enduring favorite still has many fans today.

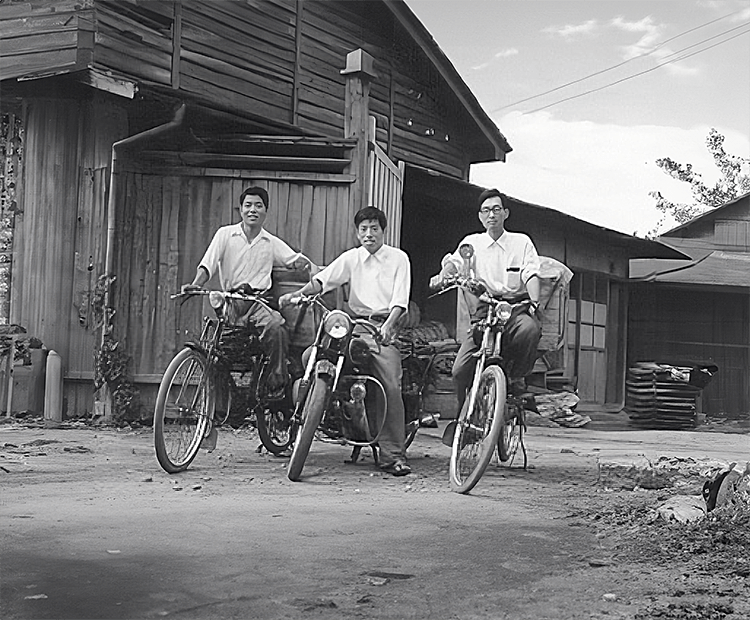

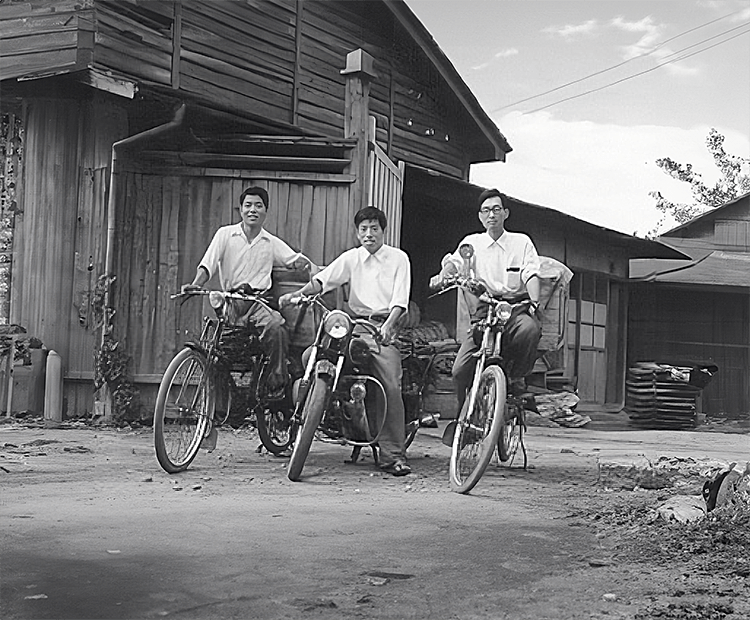

Right: Photo from Murata Shoten’s early days. Natto was delivered by bicycle back then. Minoru is the man on the motorcycle in the middle.

Hyoe was succeeded at the helm by Shigeru’s father, Murata Minoru.

“My father was quite an artisan. He helped improve the quality of Issa Natto and turned it in to what it is today. He revamped the factory in 1989 and developed many new natto products made with soybeans grown in Hokkaido and elsewhere in Japan. But the business climate became increasingly difficult as the years went by.”

Where did the natto market stand in those days? In postwar Japan, consumption of traditional Japanese processed soybean products like tofu and miso had gradually declined as people’s diet changed. The sole exception was natto, consumption of which kept rising. There were several reasons for this. In 1986, the discovery was announced of a new enzyme produced by the natto bacillus during the fermentation process, called nattokinase. This led to a flurry of interest in natto as a superfood. Meanwhile, the biggest natto producers vied to set up sales offices and build factories in western Japan to cater to consumers in that part of the country, where natto hadn’t been eaten before. They began bringing out natto with a less pungent smell, attaching sauces tailored to consumers’ tastes, and selling natto in ready-to-eat styrofoam containers. Natto made with large or medium-sized beans had previously been the norm, but with the advent of the styrofoam container, smaller natto beans gained ground.

“My grandfather’s journal from the time refers to ‘small-bean natto in a styrofoam container, complete with a packet of sauce.’ It was a pretty groundbreaking product, I guess.”

The health craze that swept the country in 2000 accelerated these trends. As the Japanese diet became increasingly homogenized under media influence, natto entered a new era of mass production and price wars on a nationwide scale (source: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries documentation). In 1996, amid these developments, Shigeru assumed the reins of Murata Shoten, having built up experience under Minoru’s guidance since 1990.

“When I took over, there was what we called the hundred-yen wall. A set of three fifty-gram containers of natto wouldn’t sell for more than a hundred yen. The products made by the big brands had penetrated every corner of the country. They were commonly sold at reduced prices for days on end. We’d already stopped making natto wrapped in kyogi sheets during my father’s day. We couldn’t make ends meet using domestically grown soybeans because they were so expensive. We left it to the wholesaler to source our beans, and a lot of them were American- or Canadian-grown. The supermarket we did business with urged us to produce larger quantities and lower the price, so we gave it a try. Well, we ended up working flat out with barely time to sleep. That made me painfully aware that we simply didn’t have what it took to be a mass producer. The big brands, of course, performed an important function by bringing cheap products to shoppers when household finances were strained. That I admit. But what we needed to do was something different than just follow suit.”

For a time, Shigeru found himself at the mercy of market forces. But when he looked back on Murata Shoten’s past, he realized that it had a history all its own. It had started out producing natto inspired by a haiku of Issa, the famed Nagano poet. And it had a proud tradition of using paper-thin wooden kyogi sheets made in the prefecture.

“I asked myself what it all meant. The answer, I realized, was that we had to find something we excelled at. At the same time, I made up my mind to stake our success on Nagano soybeans.”

Murata Shigeru is uncompromising about quality. The same routine is followed every day, yet conditions subtly vary depending on the soybeans themselves, the temperature of the water in which they’re soaked, and the air temperature. Examining the steamed soybeans is part of Shigeru’s morning routine. Not even the slightest variation escapes his notice. He then tells the production team leader what adjustments to make at the next step in the process.

Searching far and wide for Nagano-grown soybeans to make safe, great-tasting natto

While Shigeru was determined to use Nagano soybeans, he wasn’t sure where exactly to source them from. He started by purchasing whatever beans he could find and experimenting with turning them into natto. Eventually, he came across a variety of soybean that showed promise.

“The first soybean I came across that really caught my attention was one cultivated by Hama Farm, a producer in Matsumoto. They agreed to grow a small variety called Suzukomachi.” (It’s since been further improved under the name Suzuroman). “Domestically grown small soybeans varieties are in fact extremely hard to come by. They’re not very commercially viable. Natto producers are practically the only ones using them, and if they stop using them, you’re out of business. They’re too big a risk for the grower. Still, we succeeded in persuading Hama Farm to grow soybeans for us under contract by promising to provide a firm guarantee. That was in 1997.”

The high quality of the beans was of course a factor in the decision. The clincher, though, was the fact that Hama Farm had for years eschewed chemical pesticides.

“What with major pest infestations breaking out all over the country and the impact of extreme weather events, they currently follow what are called ‘special cultivation’ practices.” That means that the number of applications of pesticides targeted for reduction and the amount of chemical fertilizer used are kept beneath a certain threshold. “Even so, they still grow high-quality eco-friendly soybeans. Over the course of my dealings with Hama Farm, I’ve learned a lot about their approach to safety and the environment. These days, everybody releases their cultivation records, including the pesticides used. We refer to these while going about our job.”

The issue of genetically modified foods was stirring up controversy at the time. GM foods first appeared in Japan around 1996. Ostensibly only those confirmed to be safe were sold, but in fact consumers didn’t even know which products were which. It wasn’t until five years later, in 2001, that labeling requirements were imposed for thirty products including soybeans (source: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare documentation).

“Soon after we signed the contract with Hama Farm, the Nagano Seikatsu Club told us that they’d love to work with us on developing natto if we were going to use local beans.” (A Seikatsu Club is a cooperative run by the members to improve their quality of life.) “The issue of genetically modified foods was in the spotlight at the time. The Seikatsu Club made us a plaque reading ‘This Factory Refuses Genetically Modified Ingredients,’ which still hangs at the entrance to our factory. Our stance on the issue remains unchanged today. Using domestically grown beans is a matter of quality and safety, of course, but it’s also about protecting the stock. We’re not going to compromise now.”

Murata Shoten’s retail outlet Natto no Murata: The Delicious Natto Specialists opened its doors on July 10 (Natto Day), 2013. It’s a place where local shoppers can buy natto at the source. It offers a lineup of freshly made natto, including popular limited-edition items available nowhere else. Among them: Hot Spring Egg Natto.

Gaining a unique edge by being smart and working hard

Partnering with the Nagano Seikatsu Club enabled Murata Shoten to buy directly from agricultural cooperatives in the city of Nagano and its environs. One by one, Shigeru visited growers whom he viewed as potential suppliers and patiently explained his plans. In this way, he slowly but surely expanded his Nagano soybean supply network.

“We’re confident in the soybeans we use because we know the faces of the farmers who grow them. And it’s a mutual thing. The farmers tell us it’s gratifying to know what their soybeans are being used for. We now have contracts with six farms to grow soybeans ranging from small to large. It must have taken us over a decade to clinch them all. Prices fluctuated considerably in the meantime, and weather events were having an increasing impact. For that reason, we’ve signed contracts with different types of farmers so that if a particular issue arises, it doesn’t affect them all. While they’re all in Nagano, they’re in different parts of the prefecture. Some are dry-land farms, others are paddy farms. After signing a contract, we visit the farm to check how the crop is coming along. We engage in small talk and occasionally help weed the fields. We work alongside the grower to sustain the operation.”

Left: Forming a connection with Hama Farm in Matsumoto marked the beginning of Murata Shoten’s quest to make natto with Nagano soybeans while ensuring the ingredients were safe.

Right: Working with the Nagano Seikatsu Club (JA Nagano) enabled Murata Shoten to buy directly from local agricultural cooperatives in the city of Nagano and its environs.

One local business, which specialized in making the sauce and mustard that come with natto, was so supportive of Shigeru’s efforts that it approached him with an idea. The small print on the back of a typical natto container consists almost entirely of the ingredients in the sauce. It’s not uncommon for the sauce to contain chemical seasonings like amino acids, additives like thickeners, and isomerized sugars like high-fructose corn syrup. The mustard often contains artificial coloring.

“One day, this specialized manufacturer of sauce and mustard came to me with an additive-free sauce they’d concocted. It contained only the safest ingredients: soy sauce, sugar, vinegar, mirin sweet rice wine, dashi extract. They pointed out that with the right balance of flavorings, you can achieve a great flavor even without using chemical seasonings. Similarly, the mustard was made with starch syrup, fermented vinegar, table salt, lemon juice, and spices. That was a welcome idea as well.”

But even if the farmer supplies safe, quality soybeans and the manufacturer makes top-notch natto, unless consumers realize it, they’ll choose on price alone. It’s important, Shigeru points out, to ensure that retailers know the story of how the product was made.

“Safety and peace of mind are taken for granted today, but twenty or thirty years ago, you could go on and on about them, and at first people didn’t know what you were talking about. I tried to communicate as effectively as I could. I would compile documentation for retailers to read and set up briefing sessions. I asked them to act as our mouthpiece and tell consumers about our commitment and dedication as a manufacturer. And it’s paid off. Some stores have gone to great lengths to educate staff who work on the sales floor.”

Ever since his youth, Shigeru has dreamed of revitalizing the region he calls home. He has worked steadily to achieve that ambition alongside the many people he has crossed paths with making natto.

Shigeru has built his business on firm foundations by developing an extensive network of personal connections. In his search for the right soybean, he happened to come across one type by sheer chance.

“Just because a particular type of soybean tastes good in other processed soybean products, that doesn’t mean it will make good natto. Natto soybeans should be high in sugar and low in fat. I was constantly looking for soybeans like that, when one day I unexpectedly came across a lucky find. They were the most incredible soybeans. They were a variety called Nakasennari, which resembled the Chukyo beans used in my grandfather’s day. These beans came in three sizes, large, medium, and small. Makers of other processed foods all purchased large or medium beans, but they were completely uninterested in the small variety, because they were young and not quite ripe. They were therefore low in fat — which was unacceptable for miso but just great for natto. Despite their small size, they were somewhat larger than the small beans used for natto. We decided to buy them. They certainly weren’t cheap, though [laughs]. Coming across those beans was a major find.”

The eighteenth National Natto Competition was held in Utsunomiya, Tochigi Prefecture, in 2013. Entries were judged on five criteria: the natto’s appearance, aroma, stringiness, flavor, and texture. The proud winner of the top prize, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Award, was Murata Shoten’s Dosojin Natto — the natto made with Nakasennari soybeans. Shigeru’s determined quest for the best soybeans in Nagano was thus richly rewarded. After Dosojin Natto won the big prize, supermarkets completely sold out of it for several days.

Left: Medium-sized Nakasennari soybeans grown in Nagano. Murata Shoten sources attractive-looking beans of uniform color and shape.

Right: Dosojin Natto beans are plump, soft, and satisfyingly chewy and taste slightly sweet.

They are somewhat larger than typical small-sized natto beans, making this natto quite filling. The container bears the Eco Mark, certifying that the product is eco-friendly.

The birth of freeze-dried natto: a crunchy taste experience like nothing on the market before

Murata Shoten has developed natto made from all kinds of beans: large beans, small beans, crushed beans, and so forth. And it always insists on using the finest Nagano soybeans. Quite a few of its nattos have won prizes at various competitions, most notably Dosojin Natto, crowned the best natto in Japan. Now, with backing from a Nagano prefectural government agency, the company is gradually expanding its sales channels beyond Nagano into the Tokyo region and overseas to places like the United States and Taiwan. But there was a time when it struggled to develop sales channels.

“Whenever we tried to expand our business, we invariably ran into obstacles. You can’t sell natto without refrigeration equipment. You can’t sell something with only a shelf life of a week. We were constantly searching for ways around these problems.”

Then one day something caught Shigeru’s eye: freeze-dried crushed bean natto used for sprinkling on rice or putting in miso soup. There weren’t yet any freeze-dried natto products on the market designed to be eaten in their own right. And the dried natto available was typically deep-fried in palm oil. It had a firm texture and was heavily flavored with seasoning.

“Since we were in the business of making natto, we wanted to create something different, something with that great natto flavor that also had appeal as a health food. So I knocked on the door of the prefectural Industrial Technology Center.” (This center helps Nagano-based businesses upgrade their technological and research capabilities.) “They did several test production runs for us, and soon I got totally carried away. Simply drying natto resulted in a strange and wonderful new mouthfeel like I’d never experienced before. It was crunchy, yet the taste of beans filled your mouth with every bite, and then it took on that gooey natto texture.”

“Dry Natto,” a freeze-dried version of the classic Japanese treat, was perfected in 2002. It was made using Suzuroman beans, a small variety of soybean.

“It comes in two varieties, unsalted and lightly salted. Natural salt from Kochi is used, which contains so many minerals that it tastes more umami than salty. It really brings out the flavor of Japanese-grown soybeans, even more so than when you eat natto with soy sauce. This natto is only mildly salty. It’s more like a casual munchie than something you’d have with a drink.”

Dry Natto was produced on contract by a freeze-drying company for the first seven or eight years after its release. But then Murata Shoten ended up buying a freeze dryer and insourcing production. That’s Shigeru for you.

“When you contract out production, you have to stick to a timetable . That affects how the finished product turns out. If you make it in-house, you can keep working on it until you’re completely satisfied.”

Here’s how Dry Natto is made. First, the fermented soybeans are prepared. They’re then frozen to a temperature of -35˚C or less and placed in the machine, where they’re slowly heated and dried in a vacuum. The drying process takes a whopping thirty-eight hours.

“This technique is called vacuum freeze-drying. The defining feature of Dry Natto is that it’s crunchy yet regains its stickiness when you add water, replicating that classic natto flavor. It also keeps really well. It maintains its flavor for a long time.”

Because natto bacillus is resistant to heat, the number of bacilli doesn’t decrease even when the beans are freeze-dried. And so it was that a new no-fuss health food came into the world.

Dry Natto quickly became the talk of the industry. It was like nothing else on the market. One by one, young natto makers started visiting Shigeru, eager to learn how to make it at their own factory. Today you can find other brands of dry natto as well.

Left: Dry Natto. The beans themselves aren’t sticky at all, and when you first start chewing, they’re crunchy. Then umami flavors explode in your mouth with a gooeyness that’s classic natto. Besides making a great snack, Dry Natto would also go well in miso soup, omelets, salads, and all kinds of other dishes.

Right: Clockwise from upper left: Dry Natto, Black Soybean Dry Natto, Dosojin Natto, House-ground Crushed Bean Issa Natto, Azumino Large Bean Natto, Kokin Small Bean Natto, and Shikkari Small Bean Natto. Murata Shoten’s natto products are also available from their online store.

Taking the hard way has opened up new vistas.

When Shigeru took over the family business, it had fallen on hard times. As you listen to his story, he strikes you as a man who has always stuck to the path he believes, even when the going gets tough.

“A lot of what happens on the production line is still hidden behind closed doors these days, though things are more open than they used to be. Certain information isn’t released, and not everything is transparent. Natto in particular is a food concealed in a package. Until you eat it, you don’t know, for example, whether the soybeans are domestically grown or imported, right? That’s why I believe integrity is so vital in the proprietor of a manufacturing business. It’s the one thing I pride myself on never having compromised. In others’ eyes, it may look like I’ve insisted on going about things in a roundabout fashion and taking the hard way: contracting farmers to grow soybeans, developing dry natto, and all that. Certainly, it hasn’t all been smooth sailing. But somewhere inside, there’s always been this voice telling me that as long as I don’t give up, I haven’t failed. I’d like to think it’s been a good way to spend my life. There might have been another way, but now I’ll never know [laughs]. The only thing I can do is stay the course.”

Shigeru’s words conjure up an image of resilience — the resilience of a single transparent strand of natto that stretches on and on and refuses to snap.

Natto donburi: A recipe recommendation from the president himself!

The bacilli in natto are good for your health, and cooking doesn’t kill them. So it’s a great idea to use natto in omelets, miso soup, and all kinds of other things. Here’s a simple, delicious recipe for natto donburi (natto on rice) that was shared with us by the natto expert himself, Murata Shigeru. It’s made using Kokin Natto, which features small-sized beans. The trick with this recipe is to keep the egg yolk runny. This dish has a flavor that lingers on and on — like the strands of the natto it’s made with!

-

- Ingredients for a single serving

- 80 g small-bean natto

- Just under 1 tbsp stir-fry oil

- 1 egg

- Hosonegi (young green onions) cut into small round slices, katsuobushi (dried skipjack tuna flakes), and soy sauce, each to taste

- 200g hot rice

-

- Instructions

- ① Mix the natto (without adding any sauce).

- ② Heat a frying pan and coat with oil.

- ③ Place the natto in the frying pan. Shape like a donut, leaving a hole in the middle with room for the egg yolk.

- ④ Place the egg in the center.

- ⑤ Without putting on the lid, fry over low heat for about 3 minutes, until the egg is half-done and the edges of the natto are crisp.

- ⑥ Dish up the rice in a donburi bowl and top with natto and egg from Step 5. Sprinkle with hosonegi onions and katsuobushi flakes and drizzle on soy sauce. Enjoy!