Mid-Autumn Moon: Celebrating Japan’s Harvest Tradition

Sep 21,2023

Mid-Autumn Moon: Celebrating Japan’s Harvest Tradition

Sep 21,2023

The Mid-Autumn Moon falls on the fifteenth night of the eighth month of the traditional Japanese calendar. For many Japanese, it evokes images of susuki pampas grass and dumplings, of being caressed by the first cool breezes of autumn while admiring the moon. How have such customs evolved in different eras and regions of Japan? Food culture expert Kiyoshi Aya explains.

Many Japanese readers will doubtless recall displaying sprays of pampas grass on this special night, enjoying tsukimi dango or “moon-viewing dumplings,” and being spellbound by the beauty of the harvest moon. But you may not be aware of the day’s true significance and how it has traditionally been spent. For starters, then, we asked Aya when the Mid-Autumn Moon occurs and how the Japanese have celebrated it over the ages.

“The Mid-Autumn Moon is the moon seen on the fifteenth night of the eighth month of the traditional Japanese calendar. It’s one of the few events of the year still celebrated according to the old lunisolar calendar. It’s also called ‘Fifteenth Night’ or the ‘Taro Moon’ after the starchy taro. It’s generally thought of as the night of the full moon, but in some years it’s a day or two off. In China, there was a festival called the Mid-Autumn Festival, which became highly popular during the Tang Dynasty (618–907). It then reached Japan during the Heian period (794–1185). Court nobles would spend the occasion admiring the moon and composing poetry.”

In China, the Mid-Autumn Festival is second in importance only to the Spring Festival or Chinese New Year. It’s even a holiday there. Traditionally it’s an occasion when families gather, which is why it’s also called the Reunion Festival. It’s customarily celebrated by viewing the moon and making offerings of cockscomb flowers, melons, fruits, and mooncakes.

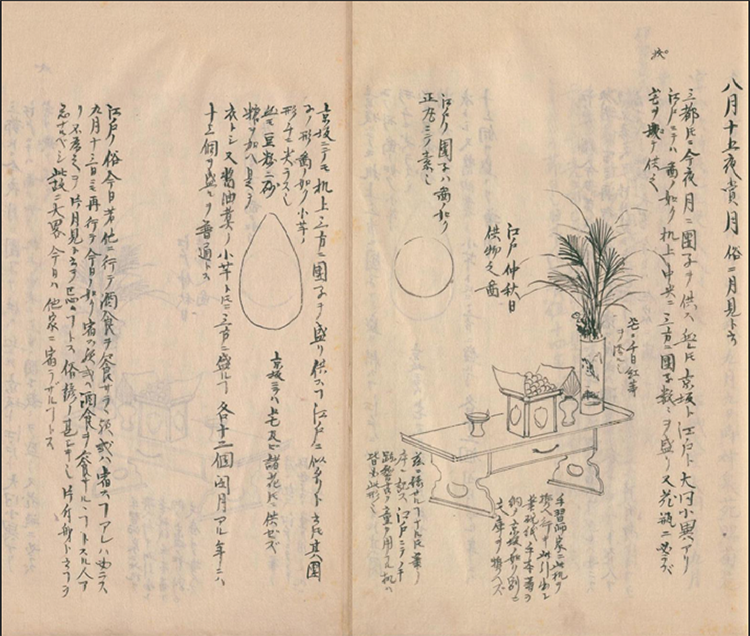

Moon-viewing in the Edo period as depicted in “Touring the Famous Sights of Edo. The Eighth Month in Takanawa. Moon-viewing Dumplings,” from the ukiyo-e print album Fūzoku Azuma Nishiki-e. Source: National Diet Library Digital Collections.

The Mid-Autumn Moon came to be celebrated by ordinary Japanese during the Edo period (1603–1868).

“In the Edo period, it became customary to offer moon-viewing dumplings on the fifteenth night of the eighth month. Offering a stack of fifteen round dumplings and displaying a spray of pampas grass next to them is a well-known custom. This practice originated in Edo, as Tokyo was then known. In the Kansai, you often see taro-shaped moon-viewing dumplings coated in bean jam. Today, susuki pampas grass is typically displayed at the Mid-Autumn Moon everywhere in Japan, but it was once common to display hagi (Japanese bush clover).”

One contemporary source, Morisada Mankō, records that round dumplings were displayed in Edo and taro-shaped dumplings in Kyoto and Osaka. Source: National Diet Library Digital Collections.

The Mid-Autumn Moon coincides with the harvest season. In many rural areas, taros and other autumn crops are offered.

“Taros have been a valued source of calories for centuries. Japanese have been eating them since before the arrival of rice cultivation in Japan. For that reason, the custom emerged of displaying taros harvested at this time of year, or dumplings shaped like them. That’s why the Mid-Autumn Moon is also known as the ‘Taro Moon.’

“There are many regional variations on moon-viewing dumplings. Shizuoka Prefecture has its famed heso dango (‘belly button dumplings’) or heso mochi (‘belly button cakes’). They’re round with a pinch in the center. And in Okinawa, you may come across a type of confection called fuchagi, which consists of rice cake coated in adzuki beans.”

Heso dango (‘belly button dumplings’) from Shizuoka Prefecture

Besides foods, Okinawa and parts of Kyushu also preserve their own distinctive Mid-Autumn Moon customs.

“Particularly famous is the Great Tug of War held in Okinawa on the fifteenth day of the eighth month of the traditional calendar to celebrate the Mid-Autumn Moon. Two teams, East and West, compete at pulling a huge rope. This, according to tradition, is a means of warding off misfortune. It’s also supposed to augur how the year will turn out. Today it’s become a huge event. Tourists visit Naha and Itoman in droves to see the Great Tug of War held in each.”

A related custom is that of celebrating the “Thirteenth Night,” which falls on the thirteenth day of the ninth month of the old calendar, about a month after the Mid-Autumn Moon. This is a native Japanese custom, unlike the Mid-Autumn Moon, which comes from China. It originated in the Heian period.

“The Thirteenth Night forms a complementary pair with the Fifteenth Night, the night of the Mid-Autumn Moon. Whereas the Fifteenth Night is called the ‘Taro Moon,’ the Thirteenth Night is sometimes called the ‘Chestnut Moon’ or the ‘Bean Moon.’ That’s because it occurs around the time when chestnuts and beans are harvested. Offerings are made to the moon as on the Fifteenth Night. These include moon-viewing dumplings, the seasonal crops chestnuts and soybeans, and fruit.

“It’s traditionally been considered lucky to view the moon from the same spot on both the Fifteenth and Thirteenth Night. Viewing the moon on just one of the two nights was referred to as katamitsuki, or ‘seeing the moon only once.’ In the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters during the Edo period, courtesans would importune customers visiting on the Fifteenth Night to come back again on the Thirteenth Night by telling them, ‘It’s unlucky to see the moon only once.’”

One Mid-Autumn Moon custom that is now obsolete except in a few parts of the country is that of “dumpling spearing” (dango-sashi or dango-tsuki).

“Dumpling spearing was a children’s custom,” Aya explains. “Children would sneak around pilfering dumplings put out as offerings on the night of the Mid-Autumn Moon. The practice was also known as otsukimi dorobō or ‘moon-view stealing.’ It’s not known exactly when it started, but it was prevalent from the Edo period until the 1920s or 1930s. Children would steal the dumplings put out as offerings on the veranda by spearing them with a long stick, and the people of the home would turn a blind eye. Having kids take your dumplings was considered lucky. It was part of the fun of the moon-viewing festival.”

In 2023, the Mid-Autumn Moon falls on September 29. The Thirteenth Night falls on October 27. “Japanese of old had many different ways of enjoying the long autumn nights,” Aya observes. “Let us too experience the wonder of the lunar spectacle while celebrating the passing of the hot summer weather and the arrival of the autumn harvest season.”

Food culture expert

Food culture expert

Kiyoshi Aya is an expert in food culture history, traditional festive foods, and local cuisine. She is the coauthor of Washoku Notebook and Hometown Foods (both published by Shibunkaku) and the author of Food Atlas (published by Teikoku Shoin). Her latest book is Enjoy the Taste of Japan with Seasonal Foods 366 Days a Year: An Illustrated Guide (published by Tankosha Publishing). She is Secretary of the Washoku Association of Japan. She also serves as a member of various food culture projects run by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and the Japan Tourism Agency.

No.1

No.2

No.3

No.4

No.5