Explore Traditional Osechi Ryori: New Year's Delicacies

Dec 28,2023

Explore Traditional Osechi Ryori: New Year's Delicacies

Dec 28,2023

In Japan at New Year’s, it’s customary to eat osechi cuisine—various foods arranged in multilayered lacquered boxes. Round rice cakes called kagami-mochi or “mirror cakes” are also displayed. When did these New Year’s traditions originate? How have they evolved in different eras and regions of Japan? Food culture expert Kiyoshi Aya explains.

Traditionally in Japan, celebrations and apotropaic rituals were held at major turning points in the calendar. New Year’s Day was particularly significant. It was when people welcomed the god of the year and prayed for an abundant harvest and a safe and peaceful year ahead. The cultural traditions associated with the New Year in Japan are thought to have emerged in and after the Nara period (710–784), according to Aya.

That’s when a series of Japanese missions to the Sui and Tang courts in China led to extensive contacts with the Asian mainland. As a result, native Japanese traditions and rituals were integrated into the cycle of annual events on the calendar borrowed from China.

“In the Heian period (794–1185), a palace ritual was held on New Year’s Day during which the emperor would worship the deities of the four quarters of heaven and earth. He would exorcise misfortune, pray for the people’s good fortune and the prosperity of their descendants, and ask the gods for a bountiful harvest. This ceremony was followed by an imperial banquet at which the ritual of hagatame or ‘tooth hardening’ was held. The banqueters would eat firm foods such as mochi rice cakes, daikon, and boar and deer meat and pray for longevity. The kagami-mochi rice cakes displayed today are thought to derive from the hagatame-mochi or ‘tooth-hardening cakes’ eaten on this occasion. An integral part of communal meals eaten on such ceremonial occasions was the idea of sharing the meal with the gods. Foods offered to the gods would be removed from the altar and eaten together by family and other members of the community in attendance. Traditional Japanese festive foods were originally intended to ward off misfortune, repel evil spirits, and pray for peace and serenity in the days and months to come through this practice of sharing a ritual meal with the gods.”

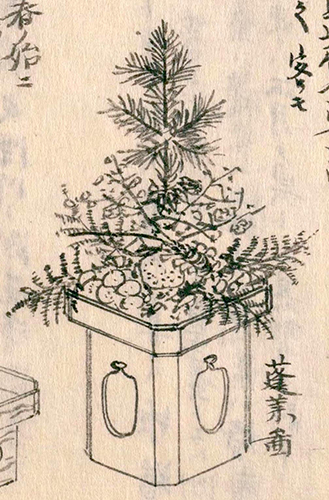

Osechi cuisine, Aya explains, originated in what is called hōrai: a festive display of food on a stand representing legendary Mount Hōrai.* The word already appears in the diary of Murasaki Shikibu, which dates to circa 1010, during the Heian period.

“Hōrai was served with sake on celebratory occasions among the Heian nobility. Then, starting in the Kamakura period (1185–1333), it was served at drinking rituals among the warrior class. Later, in the mid-Edo period (1603–1867), it came to be displayed in the tokonoma or alcove of homes in Kyoto and Osaka. In Edo, as Tokyo was then called, hōrai was known as kuitsumi or ‘stacked food’ and served to New Year’s guests. But guests would just take a small portion and bow, sources say, then put it back in its place. So it seems that the items displayed were no longer eaten; they were purely for show.

*Japanese for Mount Penglai, a legendary Chinese mountain associated with the Daoist quest for immortality and eternal youth. It was believed to lie in the Eastern Sea.

Illustration of a hōrai stand representing Mount Hōrai.* From Kitagawa Kisō (ed.), Morisada Mankō, vol. 26. Source: National Diet Library Digital Collections.

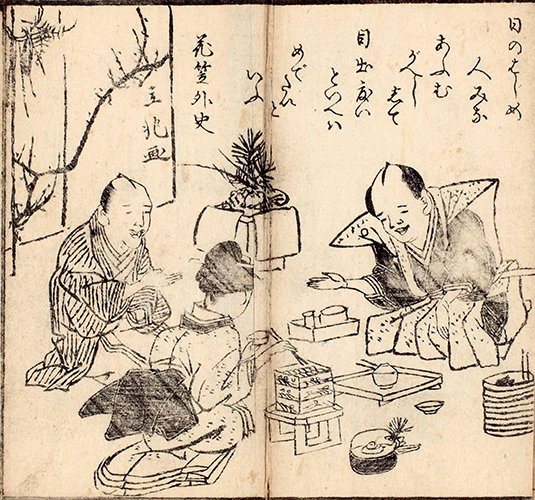

“Around the time that kuitsumi ceased to be eaten and became purely decorative, other celebratory foods served in stacked boxes appeared,” says Aya, “These included kazu no ko or herring roe, tazukuri or dried sardines cooked in soy sauce, tataki gobō or pounded burdock root, and nimame or boiled beans”—all now staples of osechi cuisine. Zōni rice-cake soup, another popular New Year’s dish, was already being eaten in the Muromachi period (1336–1573). So by this time the custom of eating osechi and zōni had emerged.

Entertaining New Year’s guests. From Nichiyō sōzaiso fuji no chinkyaku sokuseki hōchō. Source: Special Collections, Center for Collaborative Research on Pre-Modern Japanese Texts, National Institute of Japanese Literature.

The custom of celebrating the New Year and the five seasonal festivals caught on among the common people during the Edo period, and the practice of eating festive foods became widespread. Meanwhile, each region of the county developed its own distinctive culinary traditions. Shokoku fūzoku toijō kotae, a survey of local manners and customs in different parts of Japan during the Bunka era (1804–1818), asks what New Year’s foods were consumed in each region besides “herring roe, dried sardines cooked in soy sauce, pounded burdock root, and boiled beans.” Aya explains this passage’s significance.

“Herring roe, dried sardines, pounded burdock root, and boiled beans were thus eaten across the country. This has led scholars to speculate that the shogunate must have issued some type of decree requiring these four foods to be prepared for New Year’s. In addition, the text cites various New Year’s dishes specific to certain regions. These include salted salmon in what is now Nagaoka in Niigata Prefecture, and dried and simmered cod fillets in what is now Obama in Fukui Prefecture.”

Many of these foods are still served as people see off the old year and bring in the new.

In Niigata, New Year’s celebrations would not be complete without salted salmon.

Osechi cuisine retained its regional diversity until the late 1920s or 1930s. New Year’s dishes evolved in various ways in different regions of Japan. Depending on where you lived, vegetables simmered in soy sauce might be dished up on a platter at New Year’s, or an entire sea bream served to honor the occasion. But starting in the Meiji period (1868–1912), osechi cuisine became increasingly standardized in urban areas.

“Schooling was now widespread, and magazines targeting housewives came into vogue. These would feature osechi dishes on their pages, and new forms of osechi cuisine caught on, especially among city dwellers. The old staples that had been around since the Edo period—herring roe, dried sardines, pounded burdock root, boiled beans—were joined by new favorites in the Meiji period and beyond. These included kamaboko or fish cake, kinton or sweet potato puree, kobumaki or kelp rolls, and kuwai or arrowhead tubers.”

Ideas for osechi dishes with a Western or Chinese twist were already making the rounds in the Meiji and Taisho (1912–1926) periods. “There was a lot of experimenting with new forms of osechi featuring ingredients like ham or roast beef. A wider range of osechi dishes became available than ever before. These eventually evolved into the osechi we know today.”

Enjoying a New Year’s meal served in stacked lacquered boxes packed with different foods became increasingly common until the 1930s. But then the war broke out, and the food situation deteriorated. After the war, osechi cuisine came back into its own as the Japanese economic miracle took off the late 1950s and early 1960s.

At the same time, osechi became dissociated from local culinary cultures as baby boomers moved to the cities and married and the nuclear family became prevalent. The perception of osechi cuisine as a sumptuous spread, which was fostered by the media, had taken root in the public mind by the late 1960s or early 1970s. Then, as home appliances became more advanced and the retail distribution network evolved, women started entering the workforce in droves, especially after the Equal Employment Opportunities Act took effect. Meanwhile, simple-to-prepare meals caught on. More and more osechi dishes became available at the supermarket and the convenience store.

“As Japanese lifestyles have become more diverse, so have the ways people spend the New Year. But the culture of celebrating the New Year by eating osechi cuisine is alive and well. More than 70 percent of Japanese still enjoy osechi at New Year’s, according to a 2020 survey. People have more choices these days than ever. You can prepare osechi in your own kitchen. You can order it from a famous restaurant and enjoy an elaborate formal meal. Or you can just pick up a few osechi items at the convenience store. It all depends on your lifestyle. The New Year is a great opportunity to pass on your family’s osechi and zōni soup recipes to your kids. I certainly hope people will do so if they can. But there’s nothing you have to do. Choosing and enjoying the New Year’s foods right for your lifestyle is a wonderful cultural tradition. May it long endure.”

Food culture expert

Food culture expert

Born in Osaka, Kiyoshi Aya is an expert in food culture history, traditional festive foods, and local cuisine. She is the coauthor of Hometown Foods (published by Shibunkaku) and the author of Food Atlas (published by Teikoku Shoin). Her latest book is Enjoy the Taste of Japan with Seasonal Foods 366 Days a Year: An Illustrated Guide (published by Tankosha Publishing). She is Secretary of the Washoku Association of Japan. She also serves as a member of various food culture projects run by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and the Japan Tourism Agency.