Hangesho: Traditional Practices to Rejuvenate Before Summer

Jun 20,2024

Hangesho: Traditional Practices to Rejuvenate Before Summer

Jun 20,2024

In Japan, hangeshō was from olden times a significant date for those who lived by the seasons, though it’s seldom heard of anymore. Are you familiar with it? Food culture expert Kiyoshi Aya tells us more about it.

To indicate the changing seasons, the ancient Chinese divided the year into twenty-four solar terms and seventy-two pentads. This practice later spread to Japan. The term hangeshō is based on this division into seventy-two pentads. The year is divided into four seasons — spring, summer, autumn, and winter — each of which is then subdivided into six solar terms, for a total of twenty-four solar terms. The spring equinox is generally known in Japan as shunbun and the first day of autumn as risshū; both are in origin the names of solar terms. Each solar term of roughly fifteen days is further subdivided into three pentads of five days each, so that the year consists of a total of seventy-two pentads. Hangeshō is one of the seventy-two pentads. Specifically, it is the last pentad of the solar term called in Japanese geshi or the summer solstice, corresponding roughly to the five days between July 1 and 6. In Japan, hangeshō is also counted as one of the zassetsu or “miscellaneous junctures” marking significant dates in the agricultural calendar. It once fell on the eleventh day after the summer solstice. Now it falls on the day when the sun passes 100 degrees ecliptic longitude, typically around July 2. (In 2024, it falls on July 1.)

“Hangeshō has traditionally been of particular significance for those who work in the fields,” Aya explains. “The period around the summer solstice is the busiest time of the agricultural year. There was an old belief that failing to finish planting the rice seedlings and complete the farmwork by this day would result in a smaller autumn harvest. So farmers would keep busy in the fields up until hangeshō. In many regions of Japan, therefore, it became the custom to take a short break on hangeshō, which marked the end of one phase of the agricultural year. In some areas, a celebration called sanaburi was held to mark the completion of the rice planting, and farmers took a five-day holiday. Summer arrived in full force after hangeshō, which was thus the perfect time for a break to recover from fatigue.”

The name hangeshō is derived from a plant of the arum family called the karasu bishaku or “crow dipper” (Pinellia ternata). The dried rhizome of this plant, used as a traditional Chinese medicine, was brought from China to Japan. It was called banxia or “half summer” in Chinese, which in Japanese is pronounced hange. The word hange appears frequently in sources from the Heian period (794–1185). Because the flowers of the crow dipper bloom after the summer solstice, the corresponding pentad of the year came to be referred to as “the season when hange grows,” or hangeshō.

The karasu bishaku or “crow dipper” bears distinctive flowers in summer.

“Crow dipper grows in the garden of our home. It starts putting out leaves in the spring, then suddenly shoots up at the height of summer. The flowers have a rather unusual shape — they’re called ‘spathes’ — hence the name ‘crow dipper.’ The sight of crow dipper in the garden always makes me a little happy. It seems to signal the change of the seasons.”

Japanese have since olden times considered pivotal dates in the calendar a time to exorcise evil. Seasonal transitions have traditionally been marked with prayers for good health and all manner of customs. Hangeshō, too, is associated with various folk beliefs.

“Many different taboos have traditionally been observed. You mustn’t eat vegetables harvested on hangeshō, since toxic rain falls on that day. You mustn’t eat bamboo shoots on or after hangeshō, since they’re infested with insects. And be sure to put the lid on your well, as a demon will come to poison it. Thus hangeshō was meant to warn people to be careful about the food they ate. People refrained from farming on that day, which marked the arrival of the dog days of summer.”

In many places, Aya explains, the custom survives of eating foods that taste best around hangeshō as a way to ward off evil and invigorate yourself.

“The period around hangeshō is the season of the wheat harvest, and in some areas dumplings and buns are made with the newly harvested wheat. In Gifu Prefecture, for example, hage manjū — steamed buns wrapped in myoga (Japanese ginger) leaves — are eaten around this time of year. In Kochi Prefecture, they make hange dango — wheat dumplings with bean-jam filling, wrapped as in Gifu in myoga leaves. Wheat dumplings and buns associated with hangeshō are traditionally eaten in other parts of Japan as well, like hagesshō mochi in Nara Prefecture and hage dango in Kagawa Prefecture. The Kagawa Prefecture Cooperative Association of Noodle Makers has designated hangeshō ‘Udon Day.’ That’s because on hangeshō, wheat growers would customarily serve udon made with newly harvested wheat to those who had helped out with the farmwork.”

In Osaka, there are rice cakes associated with hangeshō.

“In Osaka, they make cakes consisting of half newly harvested wheat and half glutinous mochi rice. They’re eaten dusted with kinako (soybean flour). These cakes are interestingly named. In the Naka Kawachi area they’re called yoshinba. In Minami Kawachi they’re called akaneko. While there are different foods with different names, hangeshō has traditionally been spent similarly everywhere: giving thanks for the blessings of the land, and praying for good health in the days to come.”

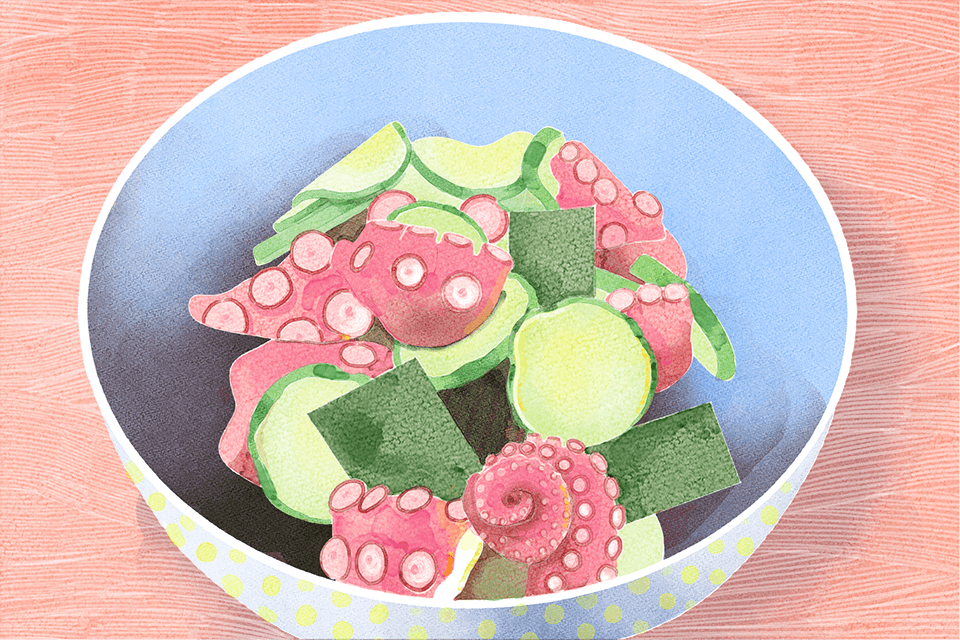

One delicacy that comes into season around hangeshō is octopus.

“Osaka Bay and the waters off Sennan have long supported a thriving octopus fishery, which peaks around hangeshō. Octopus caught around this time, known as mugiwara dako or ‘wheat straw octopus,’ has long considered the best-tasting octopus of the year. Being rich in the nutrient taurine, octopus is a restorative food for farmers tired out from planting rice. The custom spread of eating octopus with wheat cakes on this day in the hope that the freshly planted rice seedlings would put down sturdy roots like an octopus’s legs, resulting in an abundant harvest.”

Lately, more and more supermarkets have been holding campaigns urging people to eat octopus on hangeshō. The custom of eating octopus at the height of summer could well become more common.

In parts of Fukui Prefecture, especially mountainous areas like Ono, it’s customary to eat mackerel on hangeshō, according to Aya.

“Grilled whole mackerel on a skewer appears in stores in certain parts of Fukui Prefecture around hangeshō. It’s called ‘beach-grilled mackerel’ or hagessho saba (‘hangeshō mackerel’). In Ono in the Edo period (1603–1867), the custom arose of taking a break from farming on hangeshō. People would eat grilled mackerel to restore their weary limbs and fortify themselves against the summer heat.”

Why is eating mackerel so common in Ono even though it’s in the mountains?

“It’s well known that in the Edo period, mackerel was caught in large numbers in Wakasa [now southwest Fukui Prefecture] and transported to Kyoto along the Mackerel Highway. The feudal domain of Ono was located inland, but it had an enclave on the Echizen coast. Mackerel could therefore be supplied to its home territory in the mountains, and that evidently gave rise to the custom of eating mackerel on hangeshō.”

Hangeshō is seldom observed in Japan anymore. But the old custom of conditioning oneself with nutritious seasonal foods before the arrival of the hot summer months is surely still worth following today. This hangeshō, why not physically prepare yourself for the full heat of summer by dining on octopus or mackerel?

Food culture expert

Food culture expert

Born in Osaka Prefecture, Kiyoshi Aya is an expert in food culture history, traditional festive foods, and local Japanese cuisine. She is the coauthor of Hometown Foods (published by Shibunkaku) and the author of Food Atlas (published by Teikoku Shoin). Her latest book is Enjoy the Taste of Japan with Seasonal Foods 366 Days a Year: An Illustrated Guide (published by Tankosha Publishing). She is Secretary of the Washoku Association of Japan. She has also served as a member of various food culture projects run by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and the Japan Tourism Agency.