Ishibatate Koji Shop and the Handcrafted Koji Making Tools

Aug 08,2024

Ishibatate Koji Shop and the Handcrafted Koji Making Tools

Aug 08,2024

Kome-no-Hana is a koji [rice malt] outlet in Chigasaki, Kanagawa. In a previous article, we heard from the owner, Kumazawa Hiroyuki, about how he decided to become a koji maker because he wanted a fulfilling job in which accomplishments accumulate, layer by layer, “even if only as thin as a sheet of paper”. He also mentioned that the carpenters and tool makers he met were a source of support for him in his early koji-making days. Wondering what his thoughts were about those artisans and his connections with them, we visited Kome-no-Hana again, on a rainy day in early summer, to hear the rest of his story.

Kumazawa offered us tea as we gazed out the window at the rain wetting down the surrounding vegetation, which had become more verdant with the transition from spring to summer. Placed beside our tea was a red fruit that shone in the soft light of the rainy day. “I picked these plums right outside here. Try eating them with the skins on.” Following his instructions, we took a big bite and relished in the fruit’s sweetness that filled our mouths, which was soon joined by the tartness of the skin. Noting our surprise at the refreshing taste, Kumazawa added: “Many people around here look forward to this season, even greeting each other, saying: ‘Plum season is just around the corner’.”

Kumazawa Hiroyuki, owner of Kome-no-Hana

In 2011, Kumazawa started a farm on the property he inherited from his grandfather. While growing vegetables and fruits on the property throughout the seasons, he began working on Kome-no-Hana, his koji outlet, six years ago. There were no buildings on the property when he made the decision to create a koji outlet.

“The first thing I did was talk with an architect. I explained that I would be steaming rice to make the koji and that the building would have to withstand a lot of steam. The architect suggested that an Ishibatate-style construction would be a good idea for the building.”

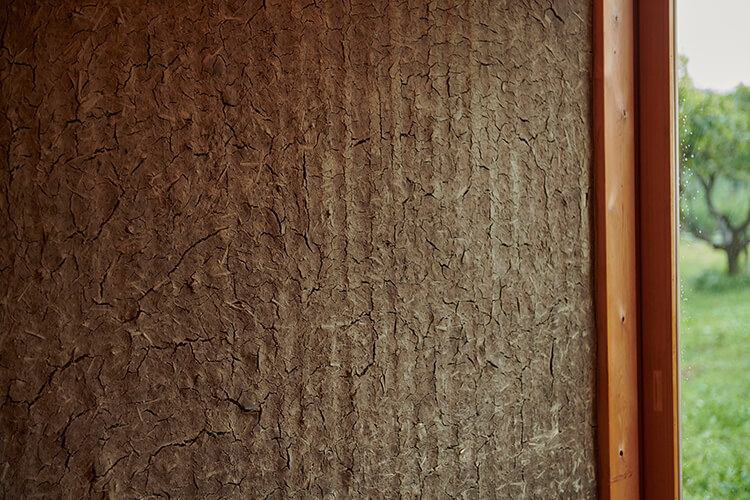

Kome-no-Hana was constructed in the Ishibatate-style

In an Ishibatate-style construction, individual foundation stones are placed under each pillar of the building. The pillars simply rest on the foundation stones without being fastened or joined in any way. It’s a traditional Japanese construction method used to build temples, shrines, and similar buildings.

“I was told that Ishibatate-style construction allows for very good ventilation underneath the building, which prevents moisture from seeping into the floor boards and walls and damaging them. I didn’t know much about the technique at the time, but the reasoning sounded convincing, so I went with it.”

An Ishibatate-style house is held in place by the weight of its clay walls and tiles, since it doesn’t have a concrete foundation like modern homes do. Kumazawa worked alongside skilled carpenters to construct the building.

The clay walls, constructed from bamboo, clay, and straw, were finished through the joint efforts of carpenters, Kumazawa, and his family

“I harvested the bamboo used as the framework for the clay walls. We dried the bamboo for about six months, removed the knots, trimmed them to length, and then wove them together. The whole family got involved in the weaving process. We coated the bamboo framework with a mixture of clay and straw. The straw came from our fields, which we fermented for about half a year before using it in the clay walls. Everything was made with local materials. We can use the same materials to make repairs as necessary. And if we decided to take down the building, all the materials could simply be returned to the soil.”

Fujioka tiles from Fujioka, Gunma, were used for the roof tiles.

“Fujioka tiles are traditional kiln-fired roof tiles. The tiles were fired by an artisan named Igarashi, who personally brought them to the site when we started roofing the building.”

Kumazawa says he will never forget the sight of Igarashi on that day.

“He was a small, thin man over 70 years old. But the sprightly way he carried himself, his attentiveness to me and the other workers, and his animated countenance left a huge impression on me. I only met him that one time, but I still remember his face and demeanor. His way of living and his humanity seemed to be manifested in his movements and posture. I thought that’s how I want to be when I grow older, and even now, I secretly regard him as a life coach.”

The roof photographed after being tiled with Fujioka tiles (Photo by Kumazawa)

Each Fujioka tile is slightly different because they are handmade one at a time. The roofers have to shape the tiles to fit together as they tile the roof before fixing them in place.

“The roofers filed and shaped warped or distorted tiles as needed on the ground before taking them up and fixing them in place on the roof. It was a tremendous job, as they had to lay 4,000 tiles this way. Although ordinary roofing tiles rarely blow off in a typhoon or strong winds, this method fastens the tiles down even more securely. The tiles themselves are very durable and are said to last for 100 to 200 years.”

After deciding to open a koji outlet, Kumazawa came to know the carpenters and roofers who helped construct the building in the Ishibatate style. He still cherishes his memories of these workers.

“I had some apprehension when I first started running the koji outlet and making koji. Whenever I felt anxious, I would recall the faces of the craftsmen who worked on the building and I would look at the walls that my family and I built with our hands, and these memories would revitalize me. They built each and every part of this building. These things gave me the energy to not allow some small complication get me down.”

Even before the building was constructed, Kumazawa had already built on his own the large vat used to steam rice. He learned how to make the vat from a barrel-maker he got to know through a friend who had started a miso store.

“Initially, I helped him out with various things under his supervision and then I started learning how to make vats. The vats are made by joining wooden boards together with bamboo nails. So right off the bat, I was taught how to make bamboo nails. I must have made hundreds of nails.”

Kumazawa also learned how to use a plane and how to fasten the boards with hoops so they won’t come loose. Over time, he completed one large vat.

“With proper maintenance and care, this vat will likely last longer than me. To keep something like this in good order, it’s very important that I can adjust it and repair it myself.”

The large vat Kumazawa made with the knowledge given to him by Oketatsu, a barrel-maker in nearby Odawara

At the same time, Kumazawa made the tools he uses in koji making.

“I made the tools I use for fluffing up and transporting steamed rice in spare moments while I was making the vat. I have to move about two kilograms of rice at a time over and over with just one hand. So I crafted the grip of the rice paddle to fit my hand and I made one side thinner so it would fluff up the rice easier. Although I made it from offcuts of some cedar floorboards, it is light, strong, and very easy to use. They don’t sell tools specifically for koji making, and it would have been expensive to have them made. Most of the tools Oketatsu uses to make barrels are handmade by the craftsmen themselves. I learned from Oketatsu that if you need something, make it.”

Kumazawa’s tools have been carved to make them easy to hold and use

Kumazawa needed to make the tools for his business, but the tool-making process itself also helped calm his nerves at the time.

“I had a lot of worries back then, after I had committed to starting this koji outlet. If I wasn’t active doing something, then my mind would start buzzing and I’d be beset by all kinds of negative thoughts — What if no customers come? What could possibly happen? To dispel these thoughts, I would keep my hands busy and make tools. I made each tool by imagining what tools I’d need in the future and what tools I can prepare now so as to stay calm should something go wrong.”

Kumazawa showed us another tool he relies on every day: an impressive broom with an exquisite shape.

“They call them Nakatsu brooms because they are made in a place named Nakatsu in Aikawa, Kanagawa. Someone told me about these brooms just as I was contemplating how best to clean Kome-no-Hana.”

Nakatsu brooms were first produced in Nakatsu sometime around the Meiji Restoration (1868) at the end of the Edo period (1603 to 1868). A local learned how to cultivate the sorghum plant — which is also called broomcorn because it’s the main material for making brooms — and manufacture brooms. Production of the brooms boomed up until the early Showa period (1926 to 1989). But with changes in lifestyles and other factors, production declined and even disappeared for a time. However, a woman whose family had been in the business for six generations began growing sorghum again and revived the Nakatsu broom.

“When I visited the Nakatsu broom store, I thought it was a cool-looking broom, but I wasn’t planning on buying one right away. However, the president, who was showing me around, told me: ‘Brooms clean more than your home; they sweep out the dust from your soul as well.’

“‘As you clean your home, you might view the dust and garbage you collect as dirty and unclean, but that dust is made up of hair fallen from your own head and bits of your clothing that have frayed and come loose.’ Those words really resonated with me. Things that we had valued become dust once they’ve served their purpose and fall by the wayside. When this happens, it’s incumbent on us to send off the things that supported us with gratitude.

“This was a lesson to me: As much as sweeping and cleaning up is about physically getting rid of dust and dirt, it is also an act of appreciation toward the things that once aided us.”

Kumazawa says that when he picked up the Nakatsu broom, it fit his body so well that he decided to keep it for life

Previously, Kumazawa had viewed cleaning as just a mundane task that needed to be done, and his only consideration was what tools are the most efficient at collecting dust and dirt. But cleaning with the Nakatsu broom has changed what time spent cleaning means to him.

“Cleaning conscientiously with this broom feels like I’m purifying myself emotionally. It’s not easy in our daily lives to always remain calm. You can’t be in that state of mind all the time. But when I pick up this broom — for which plants have been grown and fibers have been dyed and then stitched together one by one — I feel emotionally refreshed. The time I spend cleaning is like time spent maintaining my emotional well-being.”

Kumazawa uses different brooms for different locations. He made the wooden dustpan himself, as he wanted something that matched the Nakatsu brooms.

Kumazawa chuckles that all his choices — the building, the vat, his tools — are quite inefficient. In his view, however, the single-minded pursuit of efficiency is sure to become tiresome at some point.

“If you seek only greater and greater efficiencies, you won’t accrue anything within yourself. Especially in your later years when your physical strength starts to decline and you can’t stay in the same field you were in when you were younger, I believe a time will come when you feel bitter for having prioritized efficiency.

“It is the careful and deliberate accumulation of things, one at a time, that strengthens the spirit. The presence of things and people who understand this are what help you persevere. Although they may be inefficient, I feel they will ultimately take you far.”

Standing in front of the vat he made with his own hands and uses every day to make koji, Kumazawa continues.

“My life too will come to an end someday, and I would like the building and tools that I use with care to be preserved. Just as I have received energy from the tools made by people from the past, I’d like my children or others in future generations to get energy from these tools. That is my hope.”

Listening to Kumazawa as we gazed out at the pouring rain, his words seemed to suffuse our hearts.

Kome-no-Hana produces and sells koji, salted koji, and amazake and offers miso and soy sauce-making classes by appointment.