Exploring the Rich Flavor of Barrel-Brewed Soy Sauce

Sep 05,2024

Exploring the Rich Flavor of Barrel-Brewed Soy Sauce

Sep 05,2024

Soy sauce is a treasured Japanese fermented seasoning. Until the Taisho period (1912-1926), it was made in wooden barrels as a matter of course. After World War II, though, metal tanks came to predominate as the production process was automated. Only a few places have continued making soy sauce the traditional way in wooden barrels. One of them is Matsuokaya Brewery, located in the city of Iida in the Nanshin region of Nagano Prefecture. It’s the second oldest commercial establishment in Shinshu, as Nagano is traditionally known, having been founded 490 years ago in 1534. So how does Matsuokaya Brewery go about producing soy sauce? We asked the present and fifteenth head of the business, Kinoshita Hiromu, and his son and successor Kinoshita Shohei, the sixteenth in the line.

Nagano Prefecture is elongated from north to south and divided into four regions: Hokushin or North Shinshu, Toshin or East Shinshu, Chushin or Central Shinshu, and Nanshin or South Shinshu. Iida is located near the south end of the Nanshin region. It is a cultural center that originated in the thriving city that grew up around Iida Castle, which was built in the thirteenth century. Matsuokaya Brewery was founded under the name Matsuya during the civil wars of the sixteenth century by a salt merchant from the Mikawa region (present-day eastern Aichi Prefecture) who settled in Iida. It started out as a wholesaler of salt and cereals in the Honmachi Itchome district of the city, which was then prime real estate. Kinoshita Hiromu, the fifteenth head of the family, picks up the story.

“It was such a thriving concern that it was a purveyor to Iida Castle. It also let out tenements. But then in 1799, one of the tenants accidently caused a fire that grew into a massive blaze and damaged or destroyed 160 buildings. The business then moved to the Tenma-cho district. In 1818, it resumed operations under a new name, Matsuokaya Soy Sauce Shop, which produced soy sauce as well as miso and pickles. I guess they wanted to run business more efficiently by processing cereals into non-perishable soy sauce and miso. After all, there were no temperature-controlled warehouses in those days. But no written sources up to that period survive. You see, another fire struck in 1947 — the Great Fire of Iida.”

The Great Fire of Iida was the largest urban fire in postwar Japanese history. It gutted some 480,000 square meters of the city and damaged or destroyed 3,700 buildings. Consequently, almost the entire soy sauce brewery burned down, and any written records were reduced to ashes. Still, the business somehow managed to get up and running again, moving to its present location in the Imamiya-cho district under the name Matsuokaya Brewery. Its proprietor at the time was Koshio Rokuro, the thirteenth head of the family and Hiromu’s grandfather.

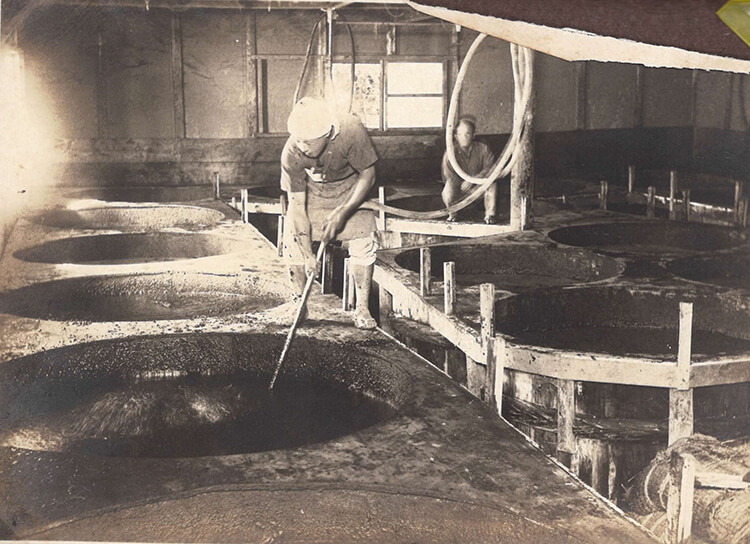

The soy sauce brewery in Tenma-cho. These valuable photos escaped the Great Fire of Iida because they were stored elsewhere. The left-hand photo shows the first day of business of the New Year, January 1922. Thirteenth househead Koshio Rokuro is on the far right.

“My grandfather may have been a soy sauce merchant, but he was a sharp dresser who went around in a suit and looked like a man of culture. He had many interests and liked to socialize. In his later years he dedicated himself to cultural pursuits like helping pass on Iida’s culture and history. His successor, the fourteenth head of the family, my father Kinoshita Kunimitsu, was an artisan through and through. He was a real stickler about the soy sauce’s flavor and quality, and he relentlessly improved the production technology. In these years Matsuokaya started entering its products in soy sauce competitions and winning numerous awards, including the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Prize. Thirty-seven sake breweries in Iida amalgamated at the time to form Kikusui Brewing. For that reason, the buildings and wooden barrels owned by many of them went out of use. Our present building originally belonged to one such brewery and was disassembled and moved here. The company also procured eight massive Japanese cedarwood barrels over two meters tall, each with a capacity of fifteen to twenty koku [one koku equals 180 liters], which are today extremely valuable. My father’s period at the helm were the go-go days, as the amount of soy sauce being shipped nationwide reached its peak. Besides acquiring the wooden barrels, he also installed what in those days was the latest equipment, such as a pressure cooker for steaming soybeans to make soy sauce. He spent boldly on plant and equipment to keep up with market demand.”

The amount of soy sauce shipped in Japan rose steadily after World War II, peaking in 1973, according to the Soy Sauce Information Center. Meanwhile, all over the country factories were becoming automated. Soy sauce factories were no exception. Factories were built where everything was automated, from regulating the temperature to managing the production line. Factories that made soy sauce the traditional way in wooden barrels faced a choice. Hiromu, now the fifteenth head of the family, agonized over which path to follow.

“Basically, we’d always taken a traditional approach to making soy sauce, which involves what’s called kanjikomi or ‘cold preparation’ — preparing the ingredients for fermentation in winter — and aging the soy sauce for an extended period. We were careful to select high-quality ingredients, even in small quantities. Certainly, sourcing ingredients in bulk and switching to automated mass production might enable us to cut costs and supply a consistent product at a low price. But I had to ask myself whether that was really the right choice. So I decided we’d remain a family business, even if that meant staying small.”

“We follow a method of making soy sauce called ‘natural brewing,’ which takes advantage of the temperature fluctuations that occur naturally over the year. The natural brewing process starts with steaming the soybeans and roasting and crushing the wheat. This is done from autumn to winter, when soybeans and wheat are harvested. The two ingredients are combined, and koji starter is mixed in to make koji. Once the koji is ready, brine is added, and the process of making the fermented mash begins. The job up to this stage is hot, grueling work, so there’s no way it can be done in summer. It’s done in the cold months, which is why it’s called ‘cold preparation.’ The mash is slowly aged for about a year from spring or summer. Right now [early summer] we’re pressing mash that’s finished aging. Smells great, doesn’t it?”

Kinoshita Hiromu engaged in pressing. The aged mash is carefully wrapped in pieces of cloth. The sheets are then piled layer upon layer, and the soy sauce filters down under its own weight, trickling out below. Once pressing is complete, the soy sauce is pasteurized and bottled. It is now ready to sell.

The aroma pervading the factory varies from season to season. When the ingredients are being prepared for fermentation, the place is filled with the sweet scent of boiled soybeans and the delicious aroma of roasted wheat. The moment I stepped into Matsuokaya Brewery, my nostrils were tickled by the indescribable fragrance of soy sauce. That was the smell of the mash being pressed. Hiromu’s son Shohei, the sixteenth in the line, was brought up experiencing this seasonal cycle of scents.

“Dad would often give me some freshly boiled soybeans to eat when I got home from school. ‘The soybeans are ready,’ he would say gleefully. ‘Want some?’ They tasted just delicious. I followed in his footsteps because I constantly saw him working away, and I wanted to have a go at it too.”

Today Hiromu’s family, Shohei’s family, and Shohei’s younger brother work together producing soy sauce. It’s been sixteen years since Shohei decided to take over the family business. Surely he can now claim to be an old hand at making soy sauce.

“No, no, not at all. I still have a lot to learn from Dad. In a soy sauce factory like this, even large pieces of equipment are manually operated, which makes the job tough. Take steaming the soybeans, for example. Tons and tons of them are steamed in one go. They’re steamed for two hours in this huge pressure cooker with the temperature raised to 120 degrees. Then the temperature is rapidly lowered to 40 degrees in half an hour. This is done using a vacuum device called an injector, and if you don’t work the valve properly, all the beans will go to waste. You can’t see the inside of the cooker, so you have to constantly keep your eye on the thermometer and the pressure gauge while imagining what’s going on inside. I’ve been observing how Dad does the job for a long time. The other day, I finally operated the valve on my own under his watchful eye.” Shohei’s passion for the job is obvious from the animated look on his face.

The steamed soybeans increase several times in weight due to the water they absorb. They’re then mixed with roasted wheat and koji spores and taken to the koji room. Here the koji is produced, which is done using a shovel. It truly is hard labor.

Hiromu with Matsuokaya Brewery’s koji room behind him. Here the koji is spread out flat on the floor. Making koji, an essential part of soy sauce production, takes three days and three nights. The men take turns working at it around the clock.

“Three men put all their strength into the job while urging each other on. Koji making is far and away the most important aspect of producing fermented foods. That applies to miso as well, which we also produce. It takes vastly more work to make koji for soy sauce than for miso, though. Koji making is intended to get the koji to produce lots of enzymes to break down the protein. Now, in the process of multiplying, koji fungus constantly generates heat, and if you just leave it, it’ll eventually die from its own heat. So the koji is turned over by human hand to create a favorable environment for it to multiply in. But the intense heat makes it a constant struggle. What’s more, koji consumes oxygen, so you have to take care it’s not starved of oxygen. The job takes three days, and we take turns working on it around the clock.

“Brine is added to the koji once we feel it’s been cultured enough. It’s then transferred to wooden barrels, where the process of making the mash begins. The koji fungus has now finished its job. The lactic acid bacteria and yeast cells growing in the barrel now set to work fermenting and aging.”

The most notable feature of wooden barrels is that the timber has tiny pores on the surface inhabited by microorganisms. These microorganisms are called resident yeast or resident bacteria. They aren’t just found in the barrels; they also inhabit the walls and the ceiling and every other nook and cranny of the soy sauce brewery. In the gloomy interior, you can almost sense the microorganisms present all around you. In a production facility with a long history like Matsuokaya Brewery, these organisms develop their own ecosystem over the years. They endow whatever fermented seasoning is made there with a character and flavor all its own.

Once the mash has finished aging, it emits a pleasant soy sauce aroma and possesses a beautifully lustrous color.

Customers occasionally drop by Matsuokaya Brewery directly to buy soy sauce. There’s a small retail outlet near the entrance that stocks soy sauce as well as miso and the sweet fermented beverage amazake. Someone — a regular, presumably — is chatting with Shohei as he waits on them. Despite the many varieties of soy sauce available in the supermarket, some people still insist on coming here to buy it. That must be because they know how good Matsuokaya’s soy sauce is. Hiromu explains.

“Until about three years ago, we had a machine for washing 1.8-liter glass bottles for putting soy sauce in. We switched to using plastic containers after it broke down. Selling soy sauce in 1.8-liter bottles became standard practice in the mid-Showa years after the war. These bottles were returnable. Glass is in fact better for soy sauce, because plastic lets air through. But households these days can’t get through huge amounts of soy sauce. We therefore developed a mini-sized 220-milliliter antioxidant airtight plastic container. These containers weren’t available on the market at the time, though they’ve become common now. We’ve been serving the local community for years, and we still have many customers who come to us directly to buy. Of course, we’ve also launched an online store now so non-locals can purchase from us as well.”

Left: Matsuokaya Brewery’s product lineup. The most popular item is Matsunishiki, a Shinshu miso that, like Matsuokaya’s soy sauce, is made in-house. It’s been beloved of the locals for over thirty years.

Right: Frozen Nama Amazake, a refreshing beverage fermented with the koji used to make miso. It has a thick, creamy, sherbet-like consistency that tastes delicious.

Matsuokaya Brewery also puts considerable effort into creating new products incorporating local ingredients. The entire family chips in ideas. The area around Iida is renowned for its fruit. The company has developed a low-sodium soy sauce made with apple juice from the neighboring town of Matsukawa. It’s also come up with a table soy sauce made with juice from yuzu picked in the village of Tenryu at the southern tip of Nagano Prefecture. Drizzle either on sashimi, and you get a dish like carpaccio. Add olive oil, and it goes great with a salad. Matsuokaya’s soy sauce isn’t just for the home. It’s also been used for decades at a historic local eatery that serves the local specialty goheimochi — skewered rice cakes coated in a sauce. And large amounts are supplied to local steakhouses — Iida has lots of places that serve meat — as well as restaurants and hotels.

“A lot of people still support our commitment to making great soy sauce. Sure, it takes a lot of time and effort to make soy sauce from scratch. But that, we believe, is the main value we deliver. As long as there are people out there who think our soy tastes great and wouldn’t settle for anything else, we’re going to stay the course.”

Left: Kinoshita Hiromu, fifteenth head of the family, president, and CEO. Developer of such products as Jidaizu (heirloom soybean) Soy Sauce and Jidaizu Yuzu Soy Sauce, both made solely from locally sourced ingredients.

Right: His slated successor Kinoshita Shohei, who will be sixteenth head of the family. He set up the company website and started selling its products online. The first person in Nagano to develop soy sauce sold in an antioxidant (airtight) container.

Producer of soy sauce, Shinshu miso, and pickled wild plants. Matsuokaya Brewery insists on using domestically sourced ingredients and preparing, aging, and turning them into finished products by hand, all at its own factory. Officially certified as the second-oldest commercial establishment in Shinshu. It has many loyal fans thanks to the great old-fashioned taste of its products. These include Whole Soybean Soy Sauce, Two Year Shinshu Miso, and Yama Gobo Pickled in Miso.

No.1

No.2

No.3

No.4

No.5