Miyasaka Brewing: Evolving Sake Brewery in Suwa, Nagano

Sep 26,2024

Miyasaka Brewing: Evolving Sake Brewery in Suwa, Nagano

Sep 26,2024

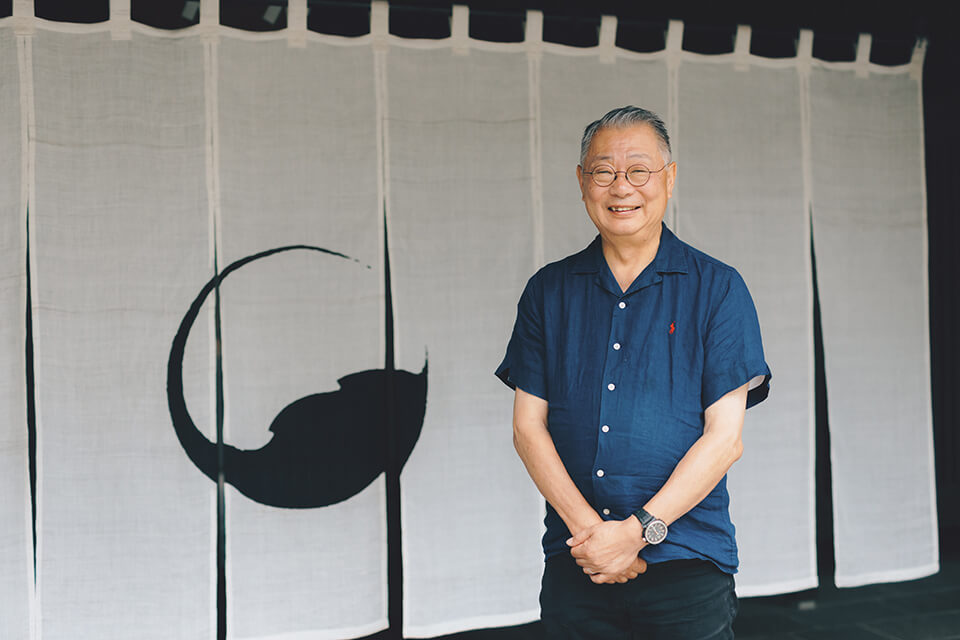

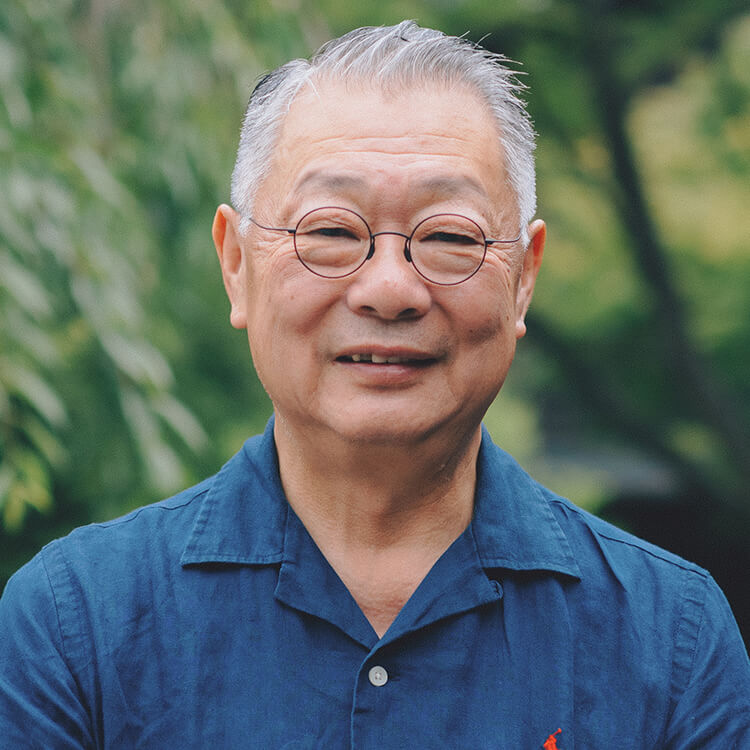

The city of Suwa lies in almost the center of the Suwa Basin in Nagano Prefecture, with Lake Suwa to the northwest and the Kirigamine Plateau to the east. It is blessed with clean air and crystal-clear waters, which over many years have run into the Suwa Basin from the Kirigamine Plateau in the form of subsurface flows. Suwa, a thriving sake brewing hub since olden times, is the home of Miyasaka Brewing, which was founded back in the Edo period (1603–1867). This venerable family brewery has experienced many ups and downs over its long history. It has faced its fair share of existential crises. It has gotten where it is today nonetheless thanks to the visionary leadership and sheer grit of the successive heads of the family. It has never rested on its laurels. We asked Miyasaka Brewing’s president Miyasaka Naotaka, who is also chair of the Nagano Sake Brewery Association, to share the company’s story.

The Miyasaka family were originally vassals of the Suwa clan. During the incessant wars of the sixteenth century, they became embroiled in fighting between the Suwa clan and the warlords Takeda Shingen and Oda Nobunaga. Then in 1662, they traded in their swords for sake making. The family became purveyors of sake to Takashima Castle, where the Suwa clan resided. They made sake under the brand name Masumi, which is derived from the name of the Suwa Shrine’s sacred mirror, Masumi no Kagami or “Mirror of Perfect Clearness.” The brewery thrived until the mid-Edo period, and many stories are still told of those days. Matsudaira Tadateru, the sixth son of the first Tokugawa shogun Ieyasu, spent much of his life in Suwa and was fond of Masumi. Otaka Gengo, one of the famed forty-seven ronin, praised its smooth taste. A lacquer drinking cup and an embossed seal box from those times are still kept as family heirlooms. Miyasaka Naotaka takes up the tale from there.

“The brewery prospered at first, but it went into steady decline from the end of the Edo period. By the Taisho era (1912-1926), it had become an impoverished sake maker on its last legs. That’s when my grandfather Miyasaka Masaru succeeded to the business at barely twenty, after my great-grandfather suddenly succumbed to illness. My grandfather didn’t know a thing about making sake or running a business. When he looked at the books, he found the company was deep in the red. He told the family he wanted to close the brewery for good, but they were adamantly opposed on the grounds of its long history. My grandfather then made up his mind to turn the family business around. And he appointed a new brewmaster — a young brewery worker around his own age who shared his determination to make only the finest sake.”

The man’s name was Kubota Chisato, who went on to become one of the most celebrated brewmasters of his day. The two men traveled all over Japan visiting renowned breweries to seek advice on the art of sake making and how to approach it. On returning home, they honed their skills in light of what they’d learned.

“The Kamotsuru brewery in Hiroshima was particularly obliging. They taught them everything, from sake making to how to run a business. The two men looked up to Kamotsuru as their mentors and visited the place again and again. Our debt to them can never be repaid.”

Miyasaka Masaru and Kubota Chisato were determined to find the formula for the perfect sake. Their many years of hard work finally paid off after the Showa era began in 1926.

Miyasaka Masaru (left) and Kubota Chisato. In their younger days they visited renowned breweries all over Japan to study the art of sake making and how to approach it. They were determined to make the perfect sake.

“By the early 1940s, Masumi had become a regular winner at sake competitions across the country. Then in 1946, it pulled off a remarkable feat, monopolizing the three top spots at both the spring and autumn National Sake Competition. After that, a steady stream of researchers started visiting to find out why a small brewery in Suwa made such superlative sake. They wanted to know our secret. One of them was Dr. Yamada Shoichi of the National Tax Agency Brewing Research Institute. He came all the way here and went over every nook and cranny of the brewery’s interior. And he identified a new type of yeast in the sake mash. My grandfather was happy to let him have this yeast isolated from Masumi. He thought there could be no greater honor for a brewery. Dr. Yamada took the yeast back to the institute and dubbed it ‘Association Yeast No. 7.’ My grandfather and Brewmaster Kubota ensured that the brewery workers kept the place spotlessly clean, and that must have created a hospitable environment for premium yeast to grow. The two men’s hard work operated in synergy with the yeast to turn Masumi into a truly glorious sake.”

The Masumi yeast dubbed Association Yeast No. 7 started being widely distributed, and before long it had spread to breweries all over Japan. Of course, even if different breweries use the same yeast, their sake still retains its own distinctive personality depending on how and with what ingredients it’s made. Sixty years after its distribution, Association Yeast No. 7 remains in use at many breweries across the country. Indeed, it’s been described as the cornerstone of modern sake making.

Plaque at the Suwa Brewery reading, “Birthplace of Association Yeast No. 7.” The yeast was identified in 1946 by Dr. Yamada Shoichi of the Ministry of Finance’s Brewing Research Institute.

The National Tax Agency Brewing Research Institute (now the National Research Institute of Brewing) was established within the Ministry of Finance in 1904. Previously, sake had been made with whatever yeast resided in the particular brewery in question.

The quality of sake was accordingly uneven. Premium yeasts were therefore gathered from breweries all over Japan and certified as “Association Yeasts.” These were cultivated in pure culture and distributed to other breweries with the goal of improving the overall quality of sake and promoting the industry’s development. Sake is produced through two processes. The first is saccharification, or the conversion of starch — the main component of the rice from which sake is made — to sugar by the enzymes in koji (rice malt). The second is alcoholic fermentation, or the conversion of sugar to alcohol by yeast. Consistent sake production requires plenty of yeast. Large amounts are therefore cultivated in pure culture when preparing the sake starter used to make sake. Rice and water are added to the starter and slowly fermented, producing what is called moromi or sake mash. Sake is the liquid pressed from this mash. In other words, yeast is the main driver of alcoholic fermentation. Moreover, yeast is a greater determinant of a sake’s flavor than rice. It produces the acid and other olfactory compounds that give the sake its floral aroma and taste. Today, there are also yeasts developed by universities and local government research institutes. The next time you drink sake, it might be interesting to consider the yeast used.

“My father Miyasaka Kazuhiro joined the brewery in the decade following the war, after my grandfather had perfected Masumi. Now that the technology was in place, my father focused on what we would now call marketing and modernizing the facilities. In those days deliveries were still made by bicycle with a wooden crate tied to the rack. My father started making faster deliveries by buying a truck. He also developed a customer base in Tokyo. He modernized the bottling plant. And he placed TV and newspaper ads and exhibited at the Osaka Expo in 1970. My grandfather and Kubota-san made the sake and my father sold it. They were a great team. Before we knew it, we were being called the top-selling sake in southern Nagano. I remember being amazed at that.”

Domestic Japanese sake shipments peaked in 1973 (according to the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries), when the Japanese economy was growing at a breakneck pace. Kazuhiro constantly stayed ahead of the curve. He made a series of innovative moves that turned conventional industry wisdom on its head. And even bigger changes were about to happen.

“When I was in university in the late 1970s, I started figuring that I’d probably take over the family business when I graduated. Then one day my father said to me, ‘Sake makers will need at least a smattering of English from now on.’ Then he packed me off to college in the United States for two years. The place was a business school, and once we had to prepare a case study. Well, there was no way I could do a better job of analyzing an American company than could an American. I was unsure what to do, so my prof advised me to write a report on our family brewery. Writing that report allowed me to take a good look at our family business. My grandfather and father, as I later realized, were both innovators in the sake business. Having experienced poverty, they always put everything on the line. I was never told to stay true to tradition. On the contrary, both men believed that you couldn’t just keep doing the same old thing. Their shared concern was, How do we improve? What can we change? The memory of having been an impoverished sake maker was in our blood. And thank goodness it was.”

On returning to Japan, Naotaka didn’t immediately join the brewery. Instead, his father Kazuhiro set him a new task. He told him to get out and see the real world. So Naotaka became a trainee in the women’s clothing department of the Isetan department store in Tokyo’s trendy Shinjuku district. The place was then on a roll. It was a hotspot for the latest trends, with new brands constantly replacing old on the sales floor.

“The department dealt in fashions for young women, so the sales floor got a total makeover every two weeks. It was always a season ahead. Since that was my first year working full-time, I figured this must be the way things were everywhere. But in my second year I was assigned to the liquor department, where the lineup remained unchanged throughout the year, though sales were steady. It was the complete opposite of the women’s clothing department. Being in fashion or in season wasn’t a consideration. I therefore approached my boss about whether we could do something different, and he told me to think of something. On the advice of my father, I then created a product called Namazake or ‘Raw Sake.’ This was an unpasteurized sake available only in summer, and it had a floral aroma. Until then, unpasteurized sake had only been drunk in small amounts by locals with connections to the brewery that made it. It wasn’t distributed commercially or available to ordinary consumers. Its quality easily deteriorates because it’s not heat-treated, but it’s okay as long as you refrigerate it. Well, we bottled several bottles of the stuff, put it on sale, and it sold like hotcakes. Our customers loved it. ‘Sake tastes this good when you don’t pasteurize it?’ they would say. The idea then caught on of offering seasonal products in the liquor department. I came up with all kinds of ideas, like ‘Freshly Pressed This Winter,’ ‘New Sake of Spring,’ and ‘New Sake of Autumn.’ And it all stemmed from my experience working in the women’s clothing department. When the son of a sake maker goes to apprentice somewhere, usually he’ll go to a company in the same business or a bank. But I guess my father wanted me to get experience in retail. The two years I spent at Isetan in Shinjuku have had a big influence on my career as a brewer.”

The taste of Masumi is the product of several factors: rice grown in Nagano’s bountiful natural environment, the region’s crystal-clear water, and a tradition of fine craftsmanship passed down from one renowned brewmaster to the next.

Naotaka started working at Miyasaka Brewing in 1983, when business was booming. Its best-selling product was low-priced “second-grade sake,” also known as “regular sake.” The system of sake “grades” was established in 1940 and remained in place for some fifty years, serving as a benchmark for shoppers buying sake. Sakes were classified into “special grade,” “first grade,” and “second grade” in descending order of quality. Each grade of sake was priced differently. But this grading did not necessarily match how consumers rated a sake’s taste and quality when they drank it.

“Regular sake — the kind of sake that ordinary folks had with dinner each evening — literally flew off the shelves. My grandfather and father said it was our job to supply the locals with the best regular sake possible. I think they made truly top-quality regular sake. But it was too sweet for my liking. I didn’t think it tasted that good. My family members and the staff all happily drank it, though. They said it was great. Plus, having spent two years at Isetan in Shinjuku, I felt the label design and the product name weren’t quite right. When I raised objections, though, I was quickly slapped down. ‘What does a greenhorn like you know?’”

Then, in the late 1980s, the period of prosperity known as the Japanese economic bubble arrived. Sales of luxury wines, whisky, beer, and shochu all shot up, while sales of sake steadily declined nationwide.

“Regular sake had once been such a hot commodity, but then sales slumped. My father claimed it was because there was so much competition. But I thought that something needed to fundamentally change. So I ordered a label design that was to my own liking. I secretly asked the brewmaster at the time to cut down on the regular sake and make pure-rice sake instead. I tried all kinds of tricks, but then my father found out, and we got into this huge argument. Eventually microbrewed sake became all the rage, and pure-rice sake and honjozo [sake made from rice polished down to 70 percent or less] started selling well. But sales of regular sake plummeted, so our bottom line steadily deteriorated. I was head of planning at the time, and people at the company blamed me. They said it was because I wasn’t doing my job. That sure took a toll on me.”

Then Naotaka was contacted by a friend at another brewery. This friend was knowledgeable enough about wine to have taken part in wine auctions. “What you need at a time like this is a change of perspective,” he said. “Why don’t you join me on a tour of French wineries?” And so Naotaka, with several others, ended up visiting famous wineries in Bordeaux and Burgundy.

“This tour was a real eye-opener for me. Things weren’t easy for French wineries either in those days. The distribution network had expanded throughout Europe as highways were built, and cheap wine came pouring in from southern Europe. There was also a flood of imported wine from what was called the New World: New Zealand, Australia, Chile, and places like that. Against that backdrop, we visited around ten mainly small wineries. They were pulling out all the stops to survive.”

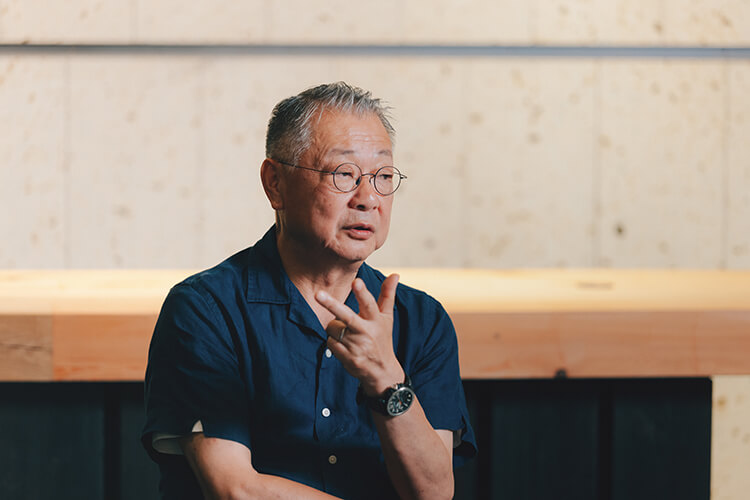

Miyasaka Naotaka describing his long-term business model for the sake industry, which draws on the lessons learned during his overseas tours.

Drawing on the lessons he learned on this visit to France and subsequent overseas tours, Naotaka proposes a business model consisting of three elements.

1. Further refine the qualities of the sake.

“This means fine-tuning the qualities of the sake to match the needs of the day. I hate to say this, but the sake my grandfather and father made didn’t taste very good. Why do I say that? Regular sake was what people drank in the postwar days when everyone in Japan was working like mad. Back then, there was even an energy drink advertised with the tagline, ‘Can you keep fighting twenty-four hours a day?’ Around Suwa, no one would have sweated away in the rice paddies all day, then arrived home and had a glass of a light-bodied dry sake. A sweet, rich sake would have been what hit the spot. But it’s not going to taste good to us, because we don’t work like that anymore. It’s only natural that different generations prefer a different-tasting sake, because lifestyles change.”

2. Put more effort into tourism.

“Bordeaux is a classic example of a medium-sized provincial city developing its economy around wine, with the entire town prospering as a result. Burgundy and the Napa Valley in California are also cases in point. This applies not only to wine but also to beer in Germany and whisky in Scotland. Producers in outlying regions attract visitors from elsewhere and thus bring life to their communities. The Japanese sake industry is still isolated and insular compared to such global centers of production. Nagano Prefecture has some eighty breweries. If it got serious about tourism, it would make an alluring destination, even by global standards.

“In 1997, as soon as I got back from France, I set up a brewery shop called Cella Masumi. The sake industry was still wholesale-oriented at the time, and for a producer to open its own retail outlet was a no-no. But I was convinced that unless we started doing stuff like that to increase tourism, nothing would ever change. The wineries in France and the Napa Vally all had their own snazzy shops, with visitors in the tasting area contentedly sipping on wine. That alone is reason enough to visit one of these destinations, right? So we started organizing five-brewery tours of Suwa. There are five sake breweries in Suwa including our own, all on the same road within five hundred meters of each other. These tours, which are given year-round, take you on a brewery-crawl of all five, and they’re been a huge hit. In 2023, after the covid pandemic ended, some ten thousand people bought tour coupons over the course of the year. The first thing I’d like to do is organize more initiatives like this all over Nagano.”

3. Put more effort into exports.

“This is a tall order unless your company is fairly large. So the first thing is to focus on tourism and attract inbound visitors. Then when they get home, they’ll spread the word about what they got to experience on their travels. And that will ultimately translate into exports.

“Of course, I’m doing what I can as chair of the Sake Brewery Association. There are several well-known wine fairs around the world. With the prefectural government’s help, we set up a Nagano booth at Vinexpo in Paris last year and this year. And next spring, we plan to have a Nagano booth at ProWein in Germany, the world’s largest trade fair of its kind. But exhibiting at a trade fair abroad isn’t likely to lead to a big contract immediately. The objective is to learn rather than to make sales. For example, you can gain insights into how to set up a booth or make a pitch, or you can take a tour of the locale.”

As you go along the historic Koshu Highway from JR Kami-Suwa Station, Miyasaka Brewing’s on-site shop Cella Masumi comes into view. It’s an imposing Japanese-style building with clean, straight lines. The white curtain fluttering in the wind between the two sturdy pillars at the entrance bespeaks integrity. It’s emblazoned in the center with an attractive brand logo modeled on the Miyasaka family crest, a sprig of ivy. The structure has the majestic appearance of a revered Shinto shrine, yet it radiates a warmth that irresistibly draws you in. On your left as you enter is a store with an exclusive selection of drinking utensils and other wares. On your right there’s the liquor shop with a full lineup of Masumi sakes. There’s also a tasting room in a separate wing. The spacious modern interior affords a view of the beautiful inner garden, which with its magnificent pine tree looks like something out of a traditional samurai home.

Cella Masumi’s tasting room. Here you can sample sake in relaxing surroundings while taking in the view of the beautiful inner garden.

“We did a rebranding five years ago. We created a brand logo and completely redesigned the label. Of course, we’ve also retained the time-honored Masumi brand name. The most important decision we made, though, was to whittle down the yeasts we used to just one, Yeast No. 7. During my time, you see, we’ve used other yeasts in the quest to achieve a bouquet with market appeal. My son Katsuhiko has been working here for eleven years now. He did exactly what he was told at first, but then he gradually started griping about things [laughs]. ‘The label’s old-fashioned. The name’s so stupid. And your sake tastes awful, Dad.’ At first I thought, ‘What the heck is he talking about?’ But come to think of it, he was saying exactly what I’d said to my own father thirty years before [laughs]. Young people, it occurred to me, are better attuned to the sensibilities and climate of the times. It was also at my son’s insistence that we decided to use nothing but Yeast No. 7. Actually, we had a product made with a blend of yeasts that was a huge hit, so the decision caused a storm of controversy in house. But there are only three sake brands in Japan that have yielded Association Yeasts: Aramasa from Akita Prefecture, which is No. 6; Masumi, which is No. 7; and Koro from Kumamoto Prefecture, which is No. 9. My son asked if we were going to abandon the honor of being a member of this trio, and that made up my mind. We released a new line of sakes that returned to our roots, Yeast No. 7, but with a revamped brand image tailored to today’s sensibilities.”

Left: Miyasaka Katsuhiko, currently director of the president’s office

Right: From left, good old-fashioned Masumi Tokusen Honjozo, and the rebranded Masumi Kuro (Black) Junmai Ginjo, Shiro (White) Junmai Ginjo, Kaya (Brown) Junmai, and Aka (Red) Yamahai Junmai Ginjo

After much trial and error, the father-and-son team of Naotaka and Katsuhiko perfected the new Masumi. A table sake suited to today’s increasingly diverse diet, it nicely brings out the flavor of the cuisine. It possesses an elegantly fruity aroma, a crisp, mild acidity, and a trace of sweetness despite its dry taste — all hallmarks of Yeast No. 7. It’s the kind of sake you could keep drinking forever.

Katsuhiko is currently director of the president’s office. One day, no doubt, he will become the driving force behind Miyasaka Brewing. After all, blood will tell. Naotaka shares one last thought.

“From now on, I believe, sake breweries should focus half on making sake and half on tourism. That’s how the wine industry grew in Europe. They could have an attached restaurant, for example, or build an auberge [a restaurant with accommodations]. We want to remain a mid-sized stalwart of the industry forever. We want to be the kind of brewery that doggedly hangs in there through good times and bad times, shining like a beacon on a hill.”

Left: The sake section of Cella Masumi with its attractive display.

Right: The housewares section offers a select assortment of items, including drinking utensils sure to create a relaxing mood at the dinner table.

President of Miyasaka Brewing, maker of the renowned sake Masumi. Born in Suwa in 1956, he is a graduate of the Faculty of Business and Commerce of Keio University. He also has an MBA from Gonzaga University in Washington State, USA. Naotaka has actively expanded into overseas markets, setting up a subsidiary in Hong Kong in 2004. Meanwhile, he served as deputy head of the Suwa Chamber of Commerce & Industry and president of the Japan Choice Brewing Association until 2016. As such, he devoted himself to promoting tourism and stimulating the sake industry’s growth. Since becoming chair of the Nagano Sake Brewery Association in 2022, he has been working to burnish the image of Nagano’s sake breweries. He loves touring historic commercial establishments, birdwatching, canoeing, building fires, reading, and hiking in the mountains.

Brewery website:

https://www.masumi.co.jp/en/

Suwa five-brewery tour website (in Japanese):

https://nomiaruki.com/tour/(諏訪五蔵 酒蔵めぐり)