Iketa Shoten: 300 Years of Fermented Dried Fish Kusaya

Oct 10,2024

Iketa Shoten: 300 Years of Fermented Dried Fish Kusaya

Oct 10,2024

The first name to come up whenever you talk about the specialties of the Izu Islands is kusaya — a salted, dried, and fermented fish that is noted for its pungency. Niijima Island, one of the nine inhabited Izu islands, is no exception. There were once more than 50 kusaya producers on the island, but their numbers have dwindled over the decades. Today, there are only four producers left on the island. For this article, we visited Kusaya no Sato [Kusaya Village], a jointly operated facility designed to pass on Niijima’s kusaya-producing tradition to the next generation. Iketa Shoten is one of the Kusaya no Sato partners. Ikemura Ryota, the fourth-generation owner of Iketa Shoten, is attempting to preserve the traditional taste of kusaya that has spanned four generations while incorporating new concepts and ideas. We spoke with him about the attractions of kusaya and its future.

“We have used our kusaya eki pickling brine, adding only water and salt, for 300 years. Without this brine, Iketa Shoten’s kusaya would not exist,” says Ikemura Ryota, the producer’s fourth-generation owner.

Kusaya eki is a kusaya producer’s most valuable possession. The brine contains a wide variety of bacteria, and the bubbles are proof that the bacteria are alive and active.

Preserving and maintaining the brine may appear easy enough, but the brine, in fact, is very delicate. The workers must pay close attention to the temperature, humidity, and the condition of the bacteria. If the brine is ever lost, it is impossible to create the same taste again. To maintain the delicate kusaya eki, it must be used regularly to soak fish.

“You can’t let the kusaya eki rest even when fish are not in season. That’s because if the brine is not used for a long period, the bacteria in the brine will lose their food source and become weak. No matter how busy you get, you have to always keep the brine active, even if it means using frozen fish. I’d love to go on a three-month vacation, but a month is about the limit, depending on the season. If I were away longer than that, the bacteria would grow weak and it would affect the taste.”

The kusaya eki is stored underneath the workplace to keep it at a constant temperature

Fermentation experts have taken notice of kusaya eki, which is the life blood of kusaya producers.

“A professor specializing in fermentation said that the way the many kinds of bacteria coexist in balance in the kusaya eki is almost miraculous. Like FC Barcelona, a football team loaded with superstars, the bacteria work together as a team to maintain perfect harmony while demonstrating their individual strengths.”

This exquisite combination of bacteria is the secret to kusaya’s taste. And beyond its use as a preserved food, kusaya is gaining attention for its health benefits as a fermented food.

“In the old days when there were no hospitals, people would drink kusaya eki straight in hopes of improving their digestion system and they would apply it to wounds as a disinfectant. With the recent fermentation trend, more attention is being paid to the health benefits of kusaya. I hope to further promote this awareness.”

“Producing kusaya may seem simple, but there’s a lot more to it than meets the eye. One important factor in producing kusaya is using the freshest fish possible.”

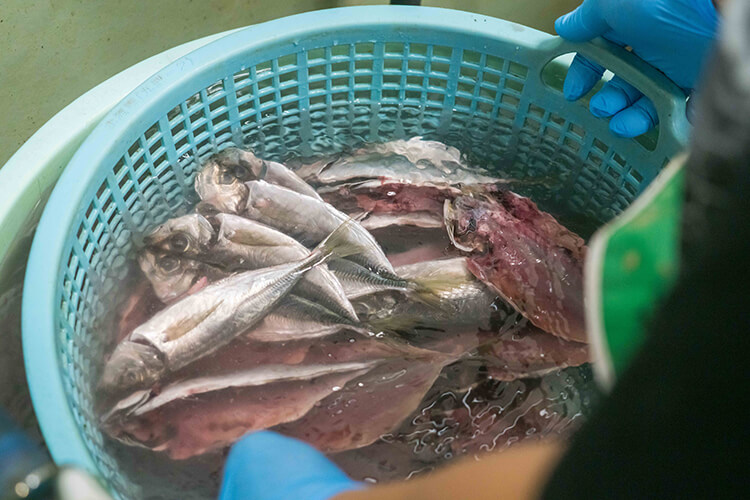

When making kusaya, it’s important to keep the fish fresh while ensuring the fermenting brine thoroughly penetrates into all of the flesh. Fish with low fat content are used, generally blue-backed fish like mackerel scad and aji horse mackerel.

“Fish with a lot of fat don’t soak up the fermenting brine well. That’s why we use blue-backed fish with low fat content, especially mackerel scad and aji horse mackerel. Because kusaya has a strong smell, people tend to believe that freshness isn’t all that important. The truth is we use fish so fresh you could eat them as sashimi.”

On the day of our visit, Ikemura was preparing ma-aji Japanese jack mackerel

Ikemura works with practiced ease, quickly filleting the fish

It takes many years of experience to gain the skills to select the best fish for the season and to fine-tune the fermentation time while accounting for the size and the fattiness of the fish.

“If the soaking time is just a little off, the fish will turn out too salty or, conversely, the taste will be too light. That’s why I have to focus on each day’s fish and pick up on their slight differences.”

The filleted fish are thoroughly washed with groundwater and then carefully deposited in the kusaya eki. How long they are soaked is adjusted for the size and oiliness of the fish.

The drying time for the fish that have been soaked all night in the kusaya eki is also adjusted while checking the firmness of the finished flesh

The history of producing kusaya on Niijima is old, dating back to the Edo period (1603 to 1868). The culture of eating fish has been rooted for centuries on Niijima, which is surrounded by the sea. The island had an old custom of preserving fish by soaking them in brine and then drying them in the sun. Because salt was a valuable resource on remote islands like Niijima, which was paid as a tax to the shogunate, the people had to reuse the brine while continually adding to it, rather than throwing it away after each use. The efficient use of limited salt resources is what led to the development of kusaya eki. As the brine was used to soak fish over and over again, it evolved into a fermenting brine that didn’t just preserve the fish but also gave it a deep umami richness and taste. This gave rise to kusaya, which became entrenched as a Niijima specialty.

A veteran fisheries worker carefully prepares the dried kusaya. Iketa Shoten’s kusaya is more impressive for its flavor than its aroma. The interview team was so surprised after taking a bite that they couldn’t help but exclaim “This is so delicious”.

“In the old days, people made kusaya at home just like they made miso and pickles at home. Our family started selling kusaya in my great-grandfather’s days. I’ve heard that prior to that, they worked as fishermen and distributed the kusaya they made to relatives. At the industry’s peak, there were some 50 producers of kusaya. When I returned to the island about 20 years ago, the number had declined to just 10. And now, only four producers survive.”

Many producers closed down because they had no successors or because the equipment they needed broke down. To slow the decline, the jointly operated Kusaya no Sato facility came into being with a subsidy from the village to protect local industry. Producers share the equipment they need at the facility as a way to cut costs while maintaining the quality of kusaya production.

Kusaya no Sato is sited in an area of abundant nature near Niijima Airport. The general public can visit the facility and observe the production work in progress.

Our modern times require that traditions be preserved while incorporating new ideas and concepts. Ikemura is taking on this new challenge not only as a fourth-generation producer but also as the Director-General of the Niijima Marine Product Processing Industry Cooperative.

“One of the things we are doing is experimenting with producing kusaya with various species of fish. Aji horse mackerel and muro-aji amberstripe scad are well suited for ordinary kusaya, but we are trying to make kusaya with red squid, an island specialty. The red squid found in the waters around Niijima is quite different from ordinary fish, so it’s hard to judge how well it will work with kusaya eki. But it has potential for discovering new flavors and textures. We are thinking outside the box like this in order to expand the range of kusaya production. Other new ideas are sharing kusaya eki, which has long been kept a secret, with people who want it and developing products, such as a kit for making kusaya at home.”

Producers have also switched over to locally sourced salt for the salt essential to kusaya eki, with the emergence of salt producers on Niijima.

Locally produced Niijima salt is added to the kusaya eki

The salt is sold in souvenir packs under the brand name Shiosai no Shio / Niijima Salt

“Island salt is different from ordinary salt in that it is smooth and round. My three-year-old daughter, who couldn’t eat kusaya before, can now eat it with relish after we switched to island salt. The people producing the salt are eager to develop Kusaya Salt and other products. I hope we can work like this with other islanders and connect the traditions of kusaya to the future through new possibilities for kusaya.”

Even as producers work on these new challenges, programs in which elementary school students can experience kusaya first hand are one initiative to promote the benefits of kusaya to more people and pass on kusaya to future generations.

“Kids learn the processes involved in kusaya production through hands-on programs at the elementary school. Some of the kids are taken aback by the smell at first, but when they actually experience the work, they realize how fun it is. Filleting the fish takes quite a bit of time initially, but after a few repetitions, they quickly get the hang of it. I feel that my role is to communicate the attractions of kusaya producing in this way to the next generation.”

These initiatives are not just about communicating the techniques to make kusaya; they are valuable opportunities to teach kids about the island’s culture and history.

“I’d be delighted if they get interested in kusaya. If they say they want to make kusaya in the future, I’ll happily share our kusaya eki with them. It would be great if we could spread and pass along kusaya like this.”

Kusaya made with great care is sold at Iketa Shoten’s store and other stores near the port

Getting to Niijima takes two hours and 20 minutes by high-speed jet ferry or eight and a half hours by overnight ferry from Tokyo’s Takeshiba Sanbashi Pier. There are also ferry services from Kurihama Port in Kanagawa and Shimoda Port in Shizuoka.

Contact Tokai Kisen at 03-5472-9999 or 0570-005710

URL:https://www.tokaikisen.co.jp/en/