Nagano Cheese: Crafting World-Class Natural Cheese in Japan

Oct 31,2024

Nagano Cheese: Crafting World-Class Natural Cheese in Japan

Oct 31,2024

Artisan cheese producer Atelier de Fromage is located on the south slopes of the foothills of Mount Asama in Tomi, eastern Nagano Prefecture, nine hundred meters above sea level. Founded in 1982, it’s renowned for pioneering the production of natural cheese in Japan. Since the release of its debut product, a fresh cheese, it’s come out with a steady stream of handmade cheeses, which were previously unknown to Japanese food culture. Today it offers a lineup of twenty cheeses, all of which have a large following thanks to their excellent taste and quality. Atelier de Fromage’s blue cheese is particularly exquisite, having won plaudits in contests at home and abroad. We talked to its creator, cheesemaker Shiogawa Kazushi, manager of cheese production and aging at Atelier de Fromage.

At Atelier de Fromage, the production staff begin their day early each morning by heading to nearby dairy farms to fetch milk. Once the pails of fresh milk are loaded on the back of the truck, they drive back to the factory, taking care not to jolt the milk too much.

“There are five dairy farms altogether,” explains Shiogawa Kazushi. “Our affiliate Fromage Bokujo and the other farms in the vicinity keep Jersey, Brown Swiss, and Holstein cattle. The milk used is of vital importance in cheesemaking. It’s fair to say that the milk determines 90 percent of a cheese’s flavor. That’s why we take good care of our cattle, collect the milk ourselves, and transport it carefully to minimize jolting.”

Atelier de Fromage is an artisan cheese producer established by Matsuoka Shigeo and his wife Yoko in 1982. There was no one seriously making cheese in Japan at the time. Then one day the couple came across some French cheese at a swanky supermarket in Tokyo, and they fell in love with it. They were seized by a desire to try making Camembert themselves. They headed to France, the home of the world’s finest cheese, and enrolled in the École Nationale d’Industrie Laitière, where they studied cheesemaking from the ground up. After returning home to Japan, they opened a cheese factory here in Tomi. The company has made numerous cheeses ever since, quite a few of which have won prizes in cheese contests in Japan and internationally. Today it offers a lineup of twenty cheeses, as well as yogurt, pizzas, and confections. It has six locations (including a pizzeria and a cafe), among them its headquarters in Tomi and two stores in Karuizawa.

On the day of our visit to the company’s headquarters in Tomi, the store was packed with shoppers from the moment it opened. The attached cafe, which is popular for its cheese dishes, bustles with visitors on weekdays and holidays alike. We immediately took a tour of the cheese factory on the second floor.

Once the milk collected from the nearby dairy farms arrives at the factory, first it’s pasteurized. Unlike the milk you usually drink, though, it’s pasteurized at low temperature to avoid denaturing the proteins. Pasteurization eliminates unwanted bacteria, but it also kills the lactic acid bacteria essential to cheesemaking. The cheesemaking process therefore begins with adding fresh lactic acid bacteria. An enzyme called rennet is added as well to harden the cheese. At the time of our visit, the curds were being cut into cubes and drained of whey.

Left: Curds being pushed to the edge of the vat with a mesh screen.

After being gathered at the edge, they’re drained of whey.

Center: The mesh screen is removed once only curd is left.

The curds are then cut and further drained.

Right: The cut curds are places in molds and pressed.

They become further condensed and, after aging, turn into cheese.

“These cut-out cubes are called curds. They’re about as firm as a fairly firm memory foam pillow. When making soft cheese, not much of the whey is drained off. When making a harder cheese, the curds are cut into smaller pieces and more of the whey is separated. They’re then placed into molds and further drained. With what is called fresh cheese, the cheese is not aged, so it’s ready to eat at this point. Other cheeses are shaped and aged after salt and microbes are added depending on the type of cheese. For example, white mold cheeses are aged after being coated with salt and white mold. Washed-rind cheeses are aged after the surface is washed with brine or alcohol. During aging, protein and fat are broken down by the action of the microbes and enzymes, and the cheese acquires a flavor and texture it didn’t possess before. The cheese may be aged for anywhere between a few weeks and a year, depending on the type of cheese. When making blue cheese, blue mold is added at the milk stage. Air is required for the mold to grow properly inside the cheese, so after shaping, salt is massaged in, and several air holes are made before the cheese is aged.”

When you look at a cross section of blue cheese, it has a marbled appearance. You’ll notice blue mold growing around the air holes. Blue cheese has a distinctive blue-mold flavor that puts many people off. But those are exactly the people that Kazushi wants to try Atelier de Fromage blue cheese.

“When you eat it, it’s like ‘Wow!’ It’s so creamy and melts in your mouth. The typical blue cheese is very salty with a pungent blue-mold flavor, but our blue cheese has a rich fullness and umami that cushion the impact. It’s got a nice balanced taste. A TV program once mentioned, by the way, that blue mold could help prevent hardening of the arteries because it breaks down fat. Well, after that, we had a sudden spike in new customers coming to buy blue cheese [laughs]. The lineup that formed before we opened included a lot of old folks. ‘Now, your blue cheese I can eat,’ people told us. ‘Our kids are still little,’ others said, ‘and even they said it tastes great.’ It was really gratifying to hear that from people who don’t usually eat blue cheese.”

No wonder Kazushi was pleased. He was the man who lovingly created Atelier de Fromage’s blue cheese. It was a tremendous feather in his cap. His blue cheese is one of chief reasons that Atelier de Fromage has become so widely known. Here’s the story of how he developed it.

Clockwise from upper left:

Camembleu, an exquisite combination of two different very different cheeses:

Camembert aged with white mold and blue cheese aged with blue mold.

Yunomaru Kogen Mountain Cheese, a mild-tasting cheese inspired

by the cheese French farmers make for themselves.

Hisui, a blue cheese characterized by its greenish-blue mold and smooth, melty texture.

Cocon, a yeasty aged creamy cheese made by blending three types of raw milk.

Kazushi was born into a dairy-farming household in Tomi. From childhood, therefore, he was familiar with the taste of freshly squeezed milk.

“How many Japanese get to drink thick milk fresh from the cow? Unless you’re a dairy farmer, you’re not likely to ever have the chance. In Japan, procedures for pasteurizing milk are set out in the Order on Milk and Milk Products (formerly the Ministerial Order on Milk and Milk Products). But the fact is, freshly drawn milk actually contains fewer bacteria. The bacteria multiply over time. Pasteurizing milk denatures the protein, affecting the taste. Knowing what milk really tastes like, I think, has helped a lot with my cheesemaking.”

Kazushi had long been familiar with Atelier de Fromage, which was also in Tomi. Indeed, it was within walking distance of his home.

“I knew the founders, Mr. and Mrs. Matsuoka, well, particularly Yoko. Her parents ran a dairy farm, and my parents and I were on friendly terms with them as neighbors. For me, Mr. and Mrs. Matsuoka weren’t so much the founders of an artisan cheese company as the man and lady who lived down the street. Thanks to that connection, I got a part-time job working in the kitchen of the restaurant attached to the factory when it opened in 1996 (Ristorante Formaggio, which has since closed). You see, I’d made up my mind to pursue a career in cooking one day. The place served basically Italian food, and many of the dishes were made with cheese.

“The head chef was a very skilled cook. He was strict, but I got a thorough grounding in how to structure the flavor of each dish. I worked there for four years, and I had plenty of opportunities to sample not just the company’s own cheeses but also cheeses from abroad. I had a personal interest in cheese, and I got to eat all kinds. I’m particularly fond of blue cheeses, and the one that made the biggest impression on me was Gorgonzola from Italy. The first time I ate it, I was dumbfounded.”

Gorgonzola is a blue cheese produced in the area spanning Italy’s Lombardy and Piedmont regions. It’s considered one of the world’s three major blue cheeses alongside France’s Roquefort and Britain’s Stilton.

“Frankly, it tasted so much better than the blue cheese Atelier de Fromage made at the time. There was no comparison. After all, cheese originally comes from abroad. Atelier de Fromage is doing pretty well for a Japanese cheesemaker, I remember thinking. It’s making an increasing variety of cheeses. But compared to the real thing, it still has a long way to go.”

Kazushi joined the cheese production team at Atelier de Fromage in 2007, seven years after he finished working part-time at the restaurant. Though at one point he had ambitions of pursuing a culinary career elsewhere, he was uncertain whether being a chef was the right life choice.

“I’d quit my previous job and happened to be visiting home, when Mrs. Matsuoka, the company’s founder, rang my father. ‘One of our production people is leaving,’ she said. ‘Can you think of anyone to replace them?’ My father replied straight off the bat, ‘Well, there’s my son.’” [Laughs.]

Left: The cafe attached to the company’s headquarters.

With its large windows, it’s a pleasant place to relax.

Right: Two popular menu items — Quattro Formaggi with House-made Blue Cheese (right)

and Baked Cheese Curry with Seasonal Vegetables (left).

By the time Kazushi joined Atelier de Fromage, the company’s original members had been replaced by a new generation.

“When I started working here, one of my senior colleagues was a person who, like Mr. and Mrs. Matsuoka, had studied at the École Nationale d’Industrie Laitière in France. That person took the time to teach me the ropes. Japanese who had studied cheesemaking in France were still a rarity then. Japan had 106 artisan cheesemakers altogether, as I recall.” (There are now some 350.)

Kazushi, who had experience as a chef and loved cheese himself, soon showed a remarkable knack for the job. Eventually he came to feel that each of the company’s products needed a rethink.

“Of the recipes followed since our founding, I thought the one for fromage frais (fresh cheese) was fine as it was. It did a good job of bringing out the flavor of the raw milk it was made from. Our hard cheeses tasted good as well, so they only needed a few tweaks. But there were a lot of cheeses that I felt needed refining. The one I most wanted to change was our blue cheese. It would sell better, I reckoned, if we altered the flavor. Around 2011, I broached the subject with Mr. Matsuoka. Well, we got into this huge argument. I still remember that clash of wills. ‘If you’re not going to let me make it the way I want to, I won’t make it at all!’ ‘Okay, since you insist, go ahead, make it then!’”

Kazushi couldn’t back down now. And so his quest to create a totally new blue cheese began. To achieve that goal, he needed to analyze Japanese taste preferences from the bottom up.

Shiogawa Kazushi doesn’t use any measuring instruments when making cheese. He believes in trusting his own well-honed sense of touch rather than relying on gadgetry. When he picks up a curd, he can instantly tell roughly how much it weights and how much salt it needs.

“Whether it’s bread or meat, Japanese people prefer their food soft, right? They like things that are soft, smooth, and sweet. Take mochi rice cakes, for instance. Japanese like rice cakes with a sweet and salty flavoring in the form of a coating of soy sauce and sugar. So what about cheese? The best-selling blue cheese in Japan at the time was Gorgonzola from Italy. Gorgonzola comes in two varieties: Piccante, which has the sharp, pungent flavor characteristic of blue mold, and Dolce, which is creamy and sweet. Well, Dolce was far and away the better seller. Japanese are put off by the pungent flavor of blue mold. So I asked myself what could be done to achieve a smooth, sweet flavor that didn’t taste strongly of blue mold.”

Kazushi now had a definite image in his mind of the blue cheese he wanted to make. The main ingredients of blue cheese are milk, lactic acid bacteria, salt, and blue mold. He started by recalibrating these ingredients from scratch, along with how they were used and in what ratios.

“When it came to milk, I experimented over and over with adding Holstein milk to Jersey milk, which is high in fat, to get the right balance. And I must have used pretty well every one of the several dozen forms of lactic acid bacteria available in Japan.

“Then there was the problem of the pungency of blue mold. Another food that tastes pungent is wasabi, right? When you eat wasabi on a slice of lean tuna, it tastes hot and spicy. But on a slice of super-fatty tuna, it doesn’t taste that hot. That’s because the fat of the tuna cushions the spicy compounds in the wasabi. The same holds for cheese. It occurred to me that the trick was how to prevent the fat in the milk from escaping. The experience I’d gained in my days working as a cook is what led me to the answer. When separating the curds and whey during the cheesemaking process, I tried various tricks, like controlling the temperature, to ensure that the curds retained as much fat as possible. When making blue cheese, you promote the growth of blue mold by creating air holes with a metal skewer after the cheese is shaped. I ultimately wanted the cheese to crumble in your mouth, so I adjusted the spacing of the holes while observing how well the blue mold was growing. I did that so the fat would break down more thoroughly. I figure I must have been at the factory 350 days out of 365, though it’s not like I kept count [laughs].”

Kazushi perfected his blue cheese at the end of 2013, after over a year and a half. It was exactly what he had envisioned: a velvety blue cheese that melts on the tongue. The full-bodied richness and umami of milk blend with blue mold to create a delightful burst of flavor in your mouth, followed by a pleasant aftertaste.

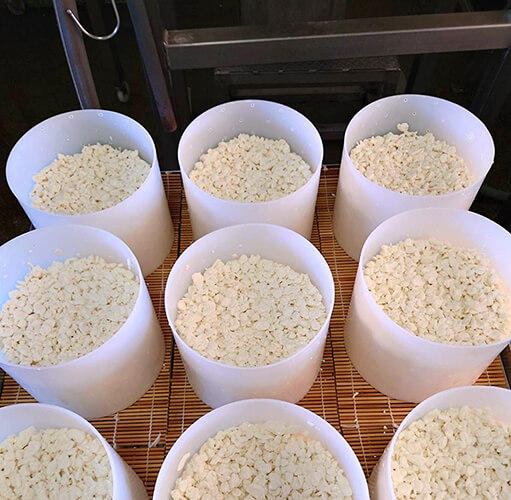

Left. Blue cheese in molds.

Right: After shaping, air holes are created to promote blue mold growth. The holes are perfectly spaced, giving the blue cheese its melty texture and rich flavor.

“Matsuoka Yoko always used to say that if you try a hundred different things, all you have to do is succeed once. Being the founders, she and Shigeo had to start from scratch, so they must have tried all kinds of things that didn’t work out. The same applies to those who followed in their footsteps. But having that pool of experience has, I believe, enabled us to take on new challenges without making the same mistakes. For that I’m truly grateful. I feel this company has a remarkable history.”

It didn’t take long for Atelier de Fromage’s new blue cheese to gain recognition for its taste and quality. The very next year, it won the grand prize at the Japan Cheese Awards 2014. Then in 2015, it bagged a Super Gold, the top award, at the international Mondial du Fromage.

“Winning these prizes was a real boon. It led to a steady increase in people who were familiar with our cheeses and eager to spread the word. Our salespeople didn’t have to do the job alone anymore. Production of blue cheese shot up 1.5 times after we won the awards. Now it’s double what it was. But the best thing of all is the confidence it’s given me as a cheesemaker. I can now say with conviction that this is Japanese blue cheese.”

Left: Besides cheese, the shop also stocks confections, pizza, and yogurt.

Right: A showcase full of cheeses. The place attracts a steady stream of shoppers who are after blue cheese.

Three years later, Kazushi developed a second blue cheese called Hisui, which means “jade.” So what kind of cheese is it?

“We started getting customers who had grown used to the taste of blue cheese and wanted something more exciting. I myself felt the need for a stronger type of cheese. That’s why I embarked on developing Hisui. I ultimately changed two things: the type of blue mold used and the moisture content. Reducing the moisture content and making the cheese more concentrated intensifies the umami and saltiness. But it also makes the cheese harder, so a blue mold with a powerful ability to break compounds down was needed to soften it. Blue molds vary in their ability to break down compounds, so I experimented with combination after combination of all the blue molds available in Japan. I think the cheese turned out nice and creamy in the end. It’s smooth and melts in your mouth in the tradition of our existing blue cheese, while also being as pungent and salty as foreign-made blue cheese. Plus the milky richness and umami strike a nice balance. The reason we called it Hisui or ‘jade’ is because it’s made with a greenish blue mold. Also, we wanted to project a Japanese image, which is why the name is written in kanji.”

At the World Cheese Awards 2021, which attracted 4,079 cheeses from 45 countries (including 37 cheeses from 25 producers in Japan), Hisui was chosen as one of the best sixteen Super Gold medal winners. It was also named Best Japanese Cheese. Kazushi has taken his blue cheese to such heights that it’s now considered the equal of anything produced overseas. What has embracing this series of challenges taught him?

“I think we found the answer by focusing on being original. We didn’t aim to create a French-based cheese. France is of course the home of the world’s finest cheese, but bringing a French cheese recipe to Japan and replicating it here isn’t going to result in an authentic French-tasting cheese. Japan started making cheese barely fifty years ago. But in France, cheesemaking goes back two thousand years. France has so many varieties of cheese that it’s often said there are as many cheeses as there are villages — thirteen hundred, to be exact.

“There’s a designation of origin system called AOP or AOC, which precisely identifies where each cheese is produced. This delimits the region where the cheese can be made and stipulates the type of milk to be used, the method of production, the method and length of aging, the cheese’s size, and even its fat content. To take the AOP for ‘Camembert de Normandie’ as an example, a cheese can’t properly claim to be Camembert unless it’s made in the Normandy region with unpasteurized Normande milk. Because it’s unpasteurized, it brings out the complex interplay of flavors unique to that locale. It almost smells of the local pastures. Thus cheese, like wine, embodies the climate and topography of the place where it’s made. If we’re going to learn anything from the French, it’s the thinking that underpins that culture. So how should we go about making cheese in Japan? Well, I figure we should make the most of the advantages of milk from locally raised cattle. And we should use the right lactic acid bacteria for that milk. It’s important to understand these traits and apply production techniques suited to them. That means, for instance, fine-tuning temperatures and times. That’s the conclusion I’ve personally come to.”

Left: The bright, relaxing cafe attached to the factory offers spectacular views.

On nice days, it’s pleasant to sit outside.

Right: A sheep leisurely grazing in front of a shed inside the enclosure in the garden.

The bucolic scenery soothes the soul.

Atelier de Fromage is situated on the south slopes of the foothills nine hundred meters above sea level. A pleasant breeze blows up the slopes and drives the clouds across the bright autumn skies. A panorama unfolds before your eyes. On a clear day, you must be able to see as far as the Chikuma River.

“Tomi has a cool climate, and it’s dry throughout the year. We don’t get much rain. Standing here, you can smell the alpine flowers, right? Cheese is a fascinating food. It tastes different depending on where it’s made and aged. There’s a product called Karuizawa Cheese. We used to make it at this factory and age it in two places, the cheese aging facility in Karuizawa and here. Karuizawa is quite damp because it’s heavily forested and foggy, and the cheese aged there smelt like well-aged pickles. The cheese aged in Tomi had a clean, flowery smell. Each tasted good in its own way. That brought home to me how much cheese is affected by the terroir. As for cattle farming, Nagano is a mountainous place, and the ranches can’t be that big. It can’t rival Hokkaido in milk quality, because Hokkaido is huge, so cattle are free to roam. Still, the cattle here live healthy lives thanks to the cool climate. And because it’s dry, there aren’t many weird bacteria. Mr. and Mrs. Matsuoka’s choice of Tomi forty-two years ago was, I have to admit, a brilliant decision. Of course, the fact that Yoko’s family lived here may have had something to do with it, but still. I think they were both true visionaries.”

Today, some 40 percent of Japan’s artisan cheese producers are in Hokkaido. That’s largely because of the favorable environment for raising dairy cattle, Kazushi believes.

“I think that Nagano’s artisan cheese producers are worth watching these days. Nagano is elongated north to south, and cheese producers are nicely distributed across the prefecture. Each of them makes their own distinctive cheese. I’ve only just started paying attention to the other producers in the vicinity [laughs], and we’ve now formed cross-connections with each other. When it comes to competitions, Hokkaido is of course formidable, but Nagano gives it a run for its money. It’s like Hokkaido and Nagano split the awards. One of the reasons Nagano is such a powerhouse, I think, is that fermented foods are its forte.

“If Hokkaido milk scores a hundred points, then Nagano milk maybe scores ninety. But as long as producers can maintain that ninety-point level through sheer effort and skill, then they’re going to be absolutely formidable. As long as I’m a cheesemaker, I’m going to remain focused on taking full advantage of what makes our milk great.”

Manager, Cheese Production and Aging

Manager, Cheese Production and Aging

Tomi native Shiogawa Kazushi is the grandson of a dairy farmer. He worked for four years as a part-time chef at the restaurant attached to Atelier de Fromage, Ristorante Formaggio, from its opening in 1996. In 2007, he joined the company’s cheese production team. The blue cheese he developed won the grand prize at the 2014 Japan Cheese Awards. In 2021, his blue cheese Hisui was named one of top sixteen in the world at the World Cheese Awards.