Preserving Japanese Pickling Culture in Nagano

Nov 28,2024

Preserving Japanese Pickling Culture in Nagano

Nov 28,2024

The quickest way to learn about a place’s culinary culture is to visit a local supermarket. Drop by any supermarket in Nagano Prefecture, and you’ll notice that the tsukemono or pickled vegetables section is every bit as extensive as the usual departments: produce, meat, fish, and all that. Pickled nozawana, a type of mustard green, is a byword for Nagano, or Shinshu as it’s historically known; but in fact the region has many different varieties of pickles. People in Nagano have unique ways of serving pickles too. One producer of tsukemono popular with the locals is Maruto in the Shinonoi neighborhood at the south end of the city of Nagano. It’s been supplying Nagano’s dining tables with pickles since 1941. We asked the CEO of this generations-old family business, Kubo Hironori, who assumed the helm last year, about Nagano Prefecture’s rich tradition of pickled vegetables — and what makes them so special.

As autumn draws to a close, the phone at pickle maker Maruto rings more often than usual. Their clientele consists mainly of local supermarkets. But that’s not who’s calling now.

“We often get phone orders for our ‘Ji-daikon’ at this time of year. This is a variety of daikon harvested every year between October and December. We slowly pickle it by aging it at low temperature, then start shipping it around December. This pickle is a limited seasonal product, and I’m pleased to say that many customers eagerly wait for it every year. We mainly sell wholesale, but if you give us a call, we’re happy to ship to individual customers.”

Ji-daikon is different from the daikon (Japanese radish) you usually see in Japan, aokubi daikon. It’s only found in this region. So what’s it like?

“There are many different native varieties of daikon all over Japan. The variety found here in the Hokushin area is called iizuna ao-daikon. It’s smaller than aokubi daikon, and it’s unusual in that the upper half near where the leaves grow is dark green, while the lower half is white. Our Ji-daikon is characterized by its firm, crunchy texture and distinctive umami. It’s flavored with delicious-smelling toasted rice bran.”

Ji-daikon is recognized for its excellent taste. It won the top award, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Prize, at the 2012 Nagano Prefectural Tsukemono Contest. On hearing that, I would have loved to try it, but it wasn’t yet in season when I visited. Tsukemono are pickled vegetables, and obviously vegetables can’t be pickled until they’re harvested. Many tsukemono can be eaten at only certain times of the year. As with vegetables, there’s a season for each.

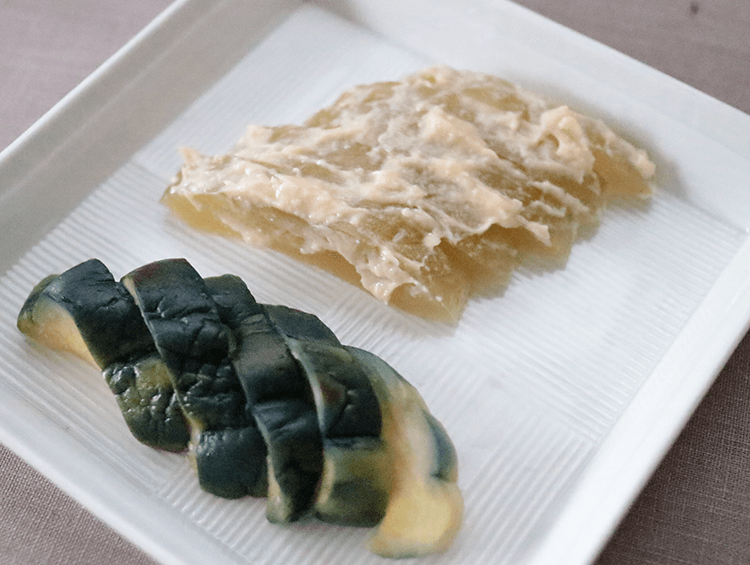

Left: Ji-daikon, a type of takuan pickle. Note its beautiful gradations of yellow and green.

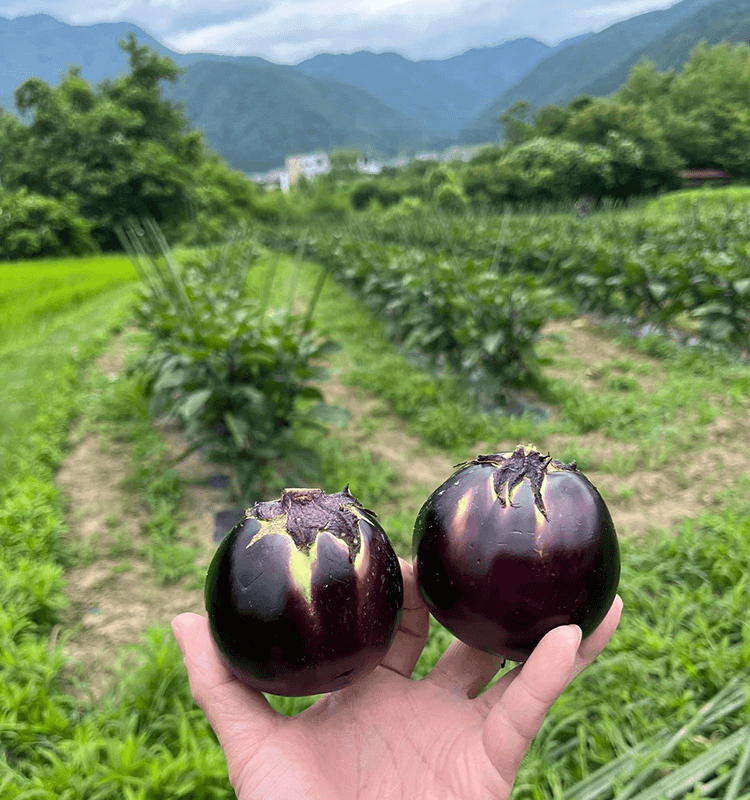

Right: Iizuna ao-daikon growing on a nearby farm. This variety of daikon is identifiable by its green upper section.

“Right now round eggplant, which is harvested between July and early September, is in season.”

With those words, I was served some maru nasu or “round eggplant” pickled in mustard. These pickles aren’t something you often see in the Kanto region around Tokyo. They’re a glossy violet color. Maru nasu resembles another type of eggplant, mizu nasu (literally “water eggplant”), only it’s slightly larger — about the size of a baseball. When you take a mouthful, the skin is firm and springy. Then as you chew on it, the pungent flavor of Japanese mustard floods your mouth. Finally comes the faintly sweet taste of eggplant. It’s a flavor that’s truly addictive.

“I’m sure you’ve never had a taste experience like this. Pickles made with the mizu nasu eggplant you get in Tokyo have a really soft skin, but these pickles have a chewier skin. I’m told that maru nasu has been harvested and eaten in Zenkojidaira since olden times. It’s a variety that doesn’t lose its shape when cooked, so it was often chopped up to use as a stuffing in oyaki buns. It then gradually came to be used for pickling as well. Another popular tsukemono here in the Hokushin area is shirouri (‘white melon’) pickled in sake lees. Despite the name, this melon is actually a greenish color; it’s also called aouri (‘green melon’) or tsukeuri (‘pickling melon’). It’s crisp and delicious when pickled. It’s harvested in the summer, pickled from early fall, and ready to eat around October.”

Left: Maru nasu (round eggplant) pickled in mustard (lower left) and shirouri (white melon) pickled in sake lees (upper right). Both effectively capitalize on the flavor and chewy texture of the vegetables used.

Right: Maru nasu is about the size of a baseball and characterized by its firm skin.

These seasonal pickles are made mainly with vegetables grown by local farmers. Hironori visits the fields more often as harvest time approaches. He wants to see how the vegetables are coming along.

“Vegetables play the starring role in tsukemono, but it’s getting harder by the year to procure them. That’s mainly because of changing conditions in the agricultural produce sector. There are fewer growers than there used to be. Plus vegetables are sown later in the year because of global warming, so the vegetables are sometimes not of high quality when harvest time comes around. There are also concerns about the impact of extreme weather events, which are becoming worse by the year. We mainly sell wholesale to local supermarkets, and as a pickle maker, we don’t want them to run out of our products. That’s why we have an extensive selection of pickles.”

Tsukemono come in many different varieties. Some are made with leaf vegetables, others with rhizomes. Their flavor differs depending on what they’re pickled in: salt, soy sauce, vinegar, miso, rice bran, koji (rice malt), sake lees. The length of time they’re pickled for varies too, from a short while in the case of asazuke or “light pickles” to several months in the case of furuzuke or “old pickles.” And the item to be pickled may be dried in the sun first, as in the case of takuan daikon and umeboshi (pickled ume fruit).

“Nagano Prefecture has many different types of tsukemono. Each region has its own varieties. Common Shinshu specialties include pickled nozawana, Shinshu koume (small pickled plums), wasabi pickles, yama gobo (pickled mountain burdock root), and miso pickles. Agricultural produce was a precious commodity in Nagano with its severe winters, so delicious ways to eat vegetables have become an established part of the region’s collective folk wisdom. Things are different now, but in the old days every household would pickle vegetables harvested in the summer and fall so they’d keep longer. They’d store them and eat them in winter. Those pickled vegetables tasted really good, which I guess is why they caught on. To give you an analogy from sushi, it’s like maguro zuke (marinated tuna). Originally, marinating the tuna was a way of making it last longer, but it tasted so good that it’s now become a popular way to serve it.”

Kubo Hironori, heir to a family business that has been making pickles for generations. He makes frequent visits to the fields as harvest time nears.

Maruto’s grounds are extensive, with seven buildings in all, each performing a different task. There’s one where ingredients are kept, one for preparing the vegetables, one for pickling them, and one for storing them. On the day of our visit, nozawana was being pickled in one of the buildings, so we got to observe how it’s done.

Pickled nozawana is a favorite among visitors to Nagano. It’s the classic Nagano gift for the folks back home. Maruto makes several varieties, including salted nozawana, nozawana pickled in wasabi, and nozawana pickled in soy sauce. Nozawana greens are distinguished by their long, slender shape. The workers at the factory were deftly folding over the nozawana before bagging it. It was that bright shade of green characteristic of lightly pickled vegetables. It looked so tender and juicy. Besides being eaten as tsukemono, nozawana pickles can also be served in other surprising ways. Hironori explains how.

“Nozawana pickles are commonly eaten as a side dish with rice or a snack with a drink. They’re a favorite snack with green tea as well. For example, at community gatherings, such as when the local fire brigade meets, there’s always a platter piled high with nozawana [laughs]. Nozawana is also used as an ingredient in various dishes. It serves as a filling for onigiri rice triangles and oyaki buns. And well fermented furuzuke nozawana, which is brown, is perfect for stir-frying or making tempura. It’s already flavored, so it tastes great with tempura dip even as is. People also put it in fried rice and pasta.”

In the tsukemono industry, they say that the best-tasing nozawana plants are those with a core about a centimeter thick, in a bunch of five or six about the width of a five-hundred-yen coin. When selecting nozawana pickles, it might be a good idea to look for ones with a thick, chunky core.

Left: Lightly pickled nozawana is prepared by washing and salting nozawana greens, then placing them in the bag with a seasoning solution.

Right: Nozawana with leaves almost a meter long. Nozawana originated several centuries ago in some Tennozu turnips brought home from Kyoto by the chief priest of a Buddhist temple in the village of Nozawa Onsen north of Nagano. He planted them there, but because of the cold climate and high altitude, the roots failed to develop and only the leaves grew. So the leaves were put to use instead by pickling them.

Maruto nozawana pickles. From left: Nozawana Pickles, Honzukuri (authentic) Nozawana Pickles, and Wasabi-flavored Nozawana Pickles.

“And it’s not just nozawana either. Pickles are served in many different ways in Nagano. There’s kimtaku gohan, for example, which combines kimchi with takuan (yellow daikon pickles). You chop the kimchi and takuan, stir-fry them with pork or bacon, and mix them with rice. This dish apparently originated when a school in Shiojiri started serving it as part of school lunches to get children eating pickles.

“Then there’s yatara, a traditional dish of the Hokushin region and a summer favorite. This is made by mincing daikon pickled in miso, myoga (Japanese ginger), and vegetables like cucumber and maru nasu eggplant, then mixing them all together. And Nagano, of course, is virtually synonymous with Shinshu miso. Cucumbers and daikon pickled in miso are household staples here, and people get really creative with miso. They use it for basting rice when making yaki onigiri (grilled rice triangles). They mix it into vinegared rice with chopped vegetables to make sushi. And then there’s namasu — julienned daikon and carrots marinated in vinegar. This is thought of as a New Year’s dish in most parts of Japan, but in Nagano, for some reason, people eat it all the time as a kind of salad.”

Left: Cucumber (left) and eggplant (right) pickled in Shinshu miso.

Right: Namasu salad made of daikon and carrots marinated in vinegar. This is eaten all the time in Nagano.

Pickling vegetables makes them chewier and more flavorful, which is why in Japan, tsukemono are perceived as stimulating the appetite. And salt plays a vital role in their production.

“Using salt is fundamental to making tsukemono, whether they’re pickled for a short time or longer. Not only does it impart a salty flavor; it also drains the vegetables of moisture, concentrating the umami. Low sodium is the order of the day, but I don’t think tsukemono taste very good without enough salt. Salt is also important to maintaining quality. Potassium chloride can be used in place of salt, and shelf life can be increased by using an acidulant or sugar to make up for the lower salt content. But I’m reluctant to make pickles that way.”

In 2000, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare established a set of guidelines titled “Health Japan 21,” which set health standards for salt intake. Excessive salt consumption, according to these guidelines, was a cause of hypertension, and “low sodium” has been the watchword ever since. Today, however, more than two decades later, the University of London INTERSALT study has concluded that salt intake raises blood pressure in some people but not in others, though those findings are disputed. Meanwhile, every summer people are now encouraged to take precautions against heat sickness. That means getting extra salt along with plenty of fluids. And in macrobiotics — a dietary regimen based on the traditional Japanese diet — salt is considered a typical yang food, yang foods being foods that warm the body. So the reason inhabitants of cold regions eat salty foods, you could argue, is to build resilience against the cold winters. This indicates that far from being a serious health threat, salt is essential to maintaining vital functions.

It’s important, then, to strike the right nutritional balance. You shouldn’t just cut down on salt because of all the talk about lowering sodium. You should understand that salt, too, is an essential nutrient and consider how to incorporate it into your daily meals.

“Today, Nagano has one of the highest life expectancies of any prefecture in Japan. I think that’s because people here eat lots of fermented foods and vegetables. Vegetables can be eaten in larger amounts when they’re pickled than when they’re fresh. That’s the great thing about tsukemono. What’s more, vegetables lose almost none of their nutrients when they’re pickled. Tsukemono are also rich in fiber, which is particularly lacking in people’s diets these days. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries has recently been running what’s called the ‘Let’s Eat Vegetables!’ project. As part of this project, people are encouraged to eat vegetables in the form of tsukemono. As a pickle maker, nothing could make us happier.”

Today, Japanese twenty and above eat an average of 280 grams of vegetables per day, according to a survey by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. That’s 70 grams less than the recommended daily intake of 350 grams. The shortfall is equivalent to one twelve-centimeter eggplant, eight okra pods, three bunches of spinach, three asparaguses, or half a tomato. Tsukemono, on the other hand, are less bulky than fresh vegetables and thus easier to eat. Moreover, almost none of the vitamins, minerals, fiber, potassium, folic acid, and other nutrients contained in the original vegetables are lost.

In other words, you only need to eat half the amount of tsukemono to obtain the nutrition available from 70 grams of vegetables. That’s 35 grams. And how much is 35 grams? Six slices or half of a salted eggplant, a small plate of lightly pickled hakusai (napa cabbage), three slices of takuan, or six slices of salted cucumber. That’s an easy enough amount to add to your daily meal plan. So using tsukemono is a great idea.

People don’t eat enough vegetable lately, and tsukemono are gradually coming into the spotlight as a way to save the day. They have a longer shelf life than fresh vegetables. They can be eaten as is or used as an ingredient in a multitude of dishes. Why not make them part of your everyday meals?

Clockwise from left: Pickled nozawana, maru nasu eggplant pickled in mustard, namasu, white melon pickled in sake lees, Shinshu cucumber pickled in miso, Shinshu eggplant pickled in miso. Orders are accepted by phone.

CEO, Maruto Co., Ltd., and Tsukemono Production Management Specialist, Grade 2

Born in 1981, Kubo Hironori is a graduate of Tokyo Keizai University. He joined Maruto in 2007 and became CEO in 2024. He enjoys playing futsal and golfing.

No.1

No.2

No.3

No.4

No.5