Toshikoshi Soba: Year-End Noodle Tradition with Buckwheat

Dec 26,2024

Toshikoshi Soba: Year-End Noodle Tradition with Buckwheat

Dec 26,2024

Many people in Japan eat a bowl of toshikoshi soba or “year-crossing buckwheat noodles” on December 31, New Year’s Eve. Today this custom is observed nationwide, but when did it originate? Does it vary from region to region? We asked food culture expert Kiyoshi Aya.

It’s often said that people in Kyoto and Osaka prefer udon or wheat noodles and Tokyoites prefer soba or buckwheat noodles. That goes back to the Edo period (1603–1867), according to Aya. First, she explains how buckwheat came to be eaten in Japan.

“In olden times buckwheat was a minor crop, and the groats were eaten unground. It’s still eaten that way today in Tokushima Prefecture under the name sobagome (‘buckwheat rice’) and in Yamagata Prefecture under the name mukisoba (‘hulled buckwheat’). For a long time, too, something called sobagaki was eaten, which consists of buckwheat flour stirred in hot water to form cakes. The buckwheat noodles or soba we know today came to be eaten, it’s believed, during the Keichō era (1596–1615) spanning the end of the Azuchi-Momoyama period and the beginning of the Edo period. They appeared under the name sobakiri.”

Sobakiri was, however, somewhat different from today’s soba. The buckwheat flour was thickened not with wheat flour but with mashed tofu or omoyu (thin rice broth). Because the noodles easily snapped, they were steamed after being quickly boiled.

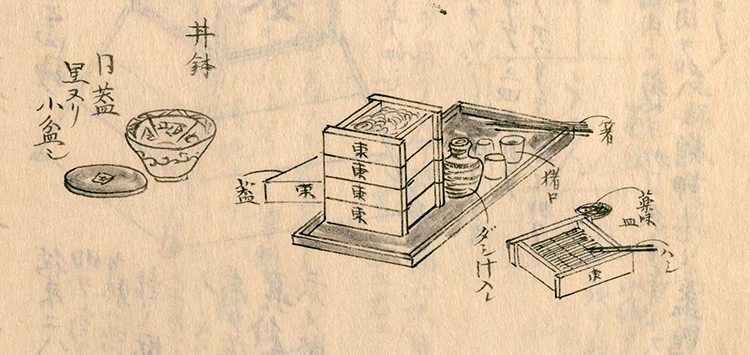

“When you go to a soba restaurant today and order mori-soba (cold noodles), the noodles will sometimes be served in what’s called a seiro or ‘steaming basket.’ That’s said to be a vestige of the days when sobakiri was steamed. Later, wheat flour came to be used as a thickener, resulting in a better-quality soba. It then became the norm to boil the soba without steaming it.”

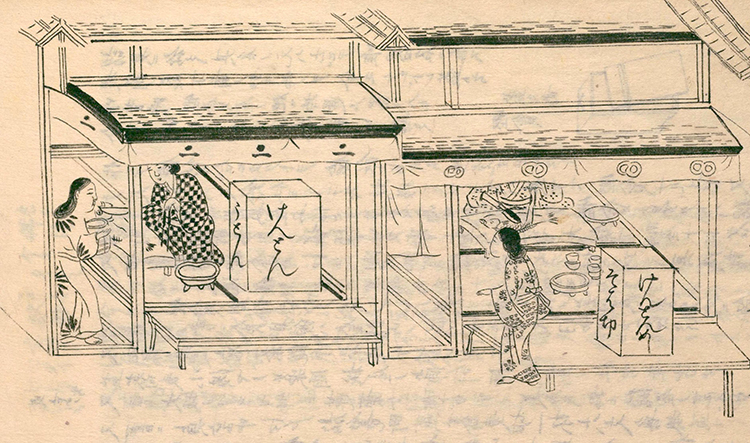

Above: A kendon-ya, as noodle shops were known in the mid-Edo period.

Below: Mori-soba was served as today on a bamboo mat in a steaming basket, a vestige of when soba was steamed, according to Aya. Kake-soba was served in a bowl. Illustrations from Morisada mankō. Source: National Diet Library Digital Collections.

The practice of eating soba rapidly caught on in the city of Edo (modern Tokyo). By the mid-Edo period, soba had come to predominate over udon.

“There were a lot of unmarried men living in Edo, so quick eat-out meals like soba, sushi, and tempura were in demand. Plus soba took less time to serve than udon, which may have appealed to the Edo temperament.”

Moreover, people in Edo were highly attuned to the latest trends, which, Aya observes, may have been a factor as well.

“Soba appears frequently in the media of the Edo period. Soba shops are portrayed in kabuki plays and depicted in ukiyo-e. They proliferated as a result, becoming popular places to go. It’s said that at their height, there were 3,700 soba shops in Edo, many of them street stalls. So soba must have been very popular indeed.”

Ukiyo-e print of soba merchants peddling soba at night in what is now the Toranomon district of Tokyo. “Aoi Slope outside Toranomon Gate,” from the series One Hundred Views of Edo by Hiroshige. Uoei, 1857. Source: National Diet Library Digital Collections.

Soba shop signs bearing the kanji for “two” and “eight” are depicted in illustrations of the day. People in Japan today would naturally assume that this refers to “two-eight soba”: soba noodles made with two parts wheat flour and eight parts buckwheat flour. But that’s apparently not what it meant back then.

“The most likely theory,” explains Aya, “is that ‘two-eight’ was a playful way of referring to the fact that a bowl of soba cost sixteen coppers. Two times eight is sixteen, so instead of writing ‘sixteen coppers,’ they displayed the kanji for two and eight.”

Back in those days it cost twelve coppers for a block of tofu, a hundred coppers for a bowl of rice topped with eel, and about thirty coppers for a haircut or shave at the barber’s. So a bowl of soba was clearly an affordable, accessible meal for the common people.

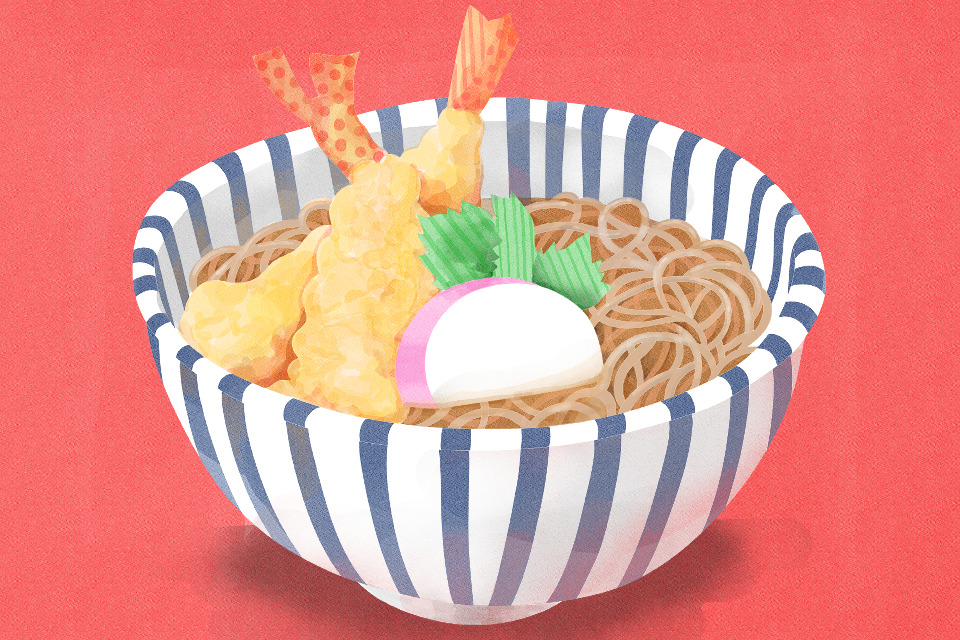

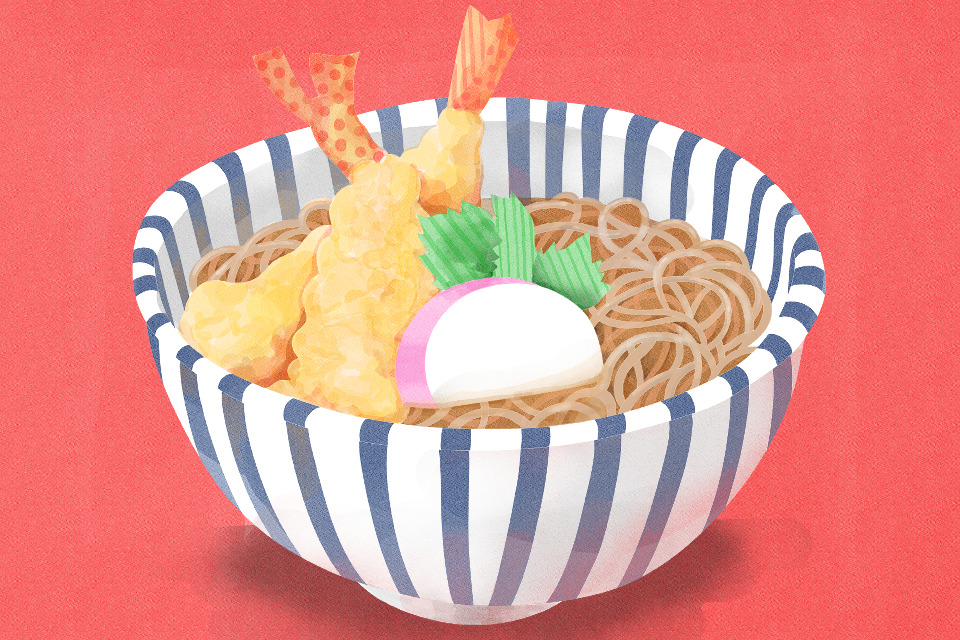

“Steamed soba predominated in the early Edo period, but when street stalls displaying two-eight signs appeared, kake-soba or buckwheat noodles served in a bowl of hot broth caught on as well. Kake-soba came in many different varieties. There was arare soba topped with small scallops, tempura soba, shippoku soba, namban soba, and so forth.”

It was also during the Edo period that people got into the habit of staying up late into the night as lamp oil became cheap.

“Soba vendors appeared who only plied their trade at night. They were called yotaka soba or ‘nighthawk noodle peddlers.’ They appear to have done a roaring trade among people who were returning from a night on the town or worked at night.”

A soba vendor with his stall in front of the theater. The characters in red read “two-eight.” “Annual Events of the Great Edo Theater: The Rumor Listener.” Hasegawa Sumi, 1897. Source: National Diet Library Digital Collections.

It wasn’t until the mid-Edo period, incidentally, that koikuchi or “dark” soy sauce became widely available enough for ordinary people to enjoy. Soba had previously been served in a simmered broth with miso dissolved in it.

“People liked to garnish their soba with pungent condiments that went well with miso. They would add things like daikon broth, grated daikon, chives, and mustard, not just the wasabi and negi green onions familiar today. When soy sauce started to catch on, it came to be used to make soba broth and dipping sauce. Soba must have become more popular than ever with the advent of soy sauce-based sauces that went well with soba. And it appears that broths and sauces became sweeter as sugar became easily available to the masses.”

In Edo, especially among the merchant class, it was customary to eat soba on the last day of the month.

“Merchants got into the habit of eating soba on the last day of each month to celebrate the end of another successful month of business. The custom of eating soba on the last day of the year, New Year’s Eve, took root in the process. The soba eaten on this occasion for good luck was variously called misoka soba (last-day soba) or un soba (fortune soba). That’s believed to be the origin of the modern custom of eating toshikoshi soba or ‘year-crossing buckwheat noodles.’”

This custom appears to have emerged in the mid-Edo period. It then spread throughout the city of Edo. On New Year’s Eve, people would flock to the soba shops in droves.

If you look at sources from the end of the Edo period, numerous records can be found of soba being eaten on New Year’s Eve in other regions of Japan as well. It seems that the practice spread from Edo to other areas and gradually caught on across the country.

So when did soba eaten on New Year’s Eve came to be called toshikoshi soba?

“It’s not known exactly. Even in sources from the Meiji period (1868–1912), the terms misoka soba, un soba, and toshikoshi soba are used interchangeably. There was no single name for the noodles, but several names coexisted with regional variations. They were first called misoka soba, the name by which they were originally known in Edo. They were also known as un soba or toshikoshi soba. Eventually, it seems, the name toshikoshi soba prevailed.

“One text from the Meiji period, Tōkyō nenchū gyōji (Annual events of Tokyo), records how soba ordered in the morning still hadn’t arrived by the time the temple bells were ringing in the New Year at midnight. So soba places clearly did a roaring trade on New Year’s Eve.”

In all eras, people have wished for a prosperous New Year. Eating soba on New Year’s Eve is a well-established part of Japanese life, an annual ritual for seeing out the old year. This New Year’s Eve, why not enjoy a bowl of soba to bid farewell to the old year and pray for happiness in the new?

Happy New Year!

Food culture expert

Food culture expert

Born in Osaka Prefecture, Kiyoshi Aya is an expert in food culture history, traditional festive foods, and local Japanese cuisine. She is the coauthor of Hometown Foods (published by Shibunkaku) and the author of Food Atlas (published by Teikoku Shoin). Her latest book is Enjoy the Taste of Japan with Seasonal Foods 366 Days a Year: An Illustrated Guide (published by Tankosha Publishing). She is Secretary of the Washoku Association of Japan. She has also served as a member of various food culture projects run by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and the Japan Tourism Agency.