Amazake Explorer: The Sweet Journey of Japanese Fermentation

Nov 15,2018

Amazake Explorer: The Sweet Journey of Japanese Fermentation

Nov 15,2018

Amazake Explorer Fujii Hiroshi operates amazake.com , a website that publishes an abundance of information on amazake [a sweet drink made from fermented rice]. He is involved in a wide range of activities to popularize the culture of brewing using amazake and koji [rice malt], including daily reviews of amazake sold around the country and holding amazake workshops.

Fujii, who has been drinking homemade amazake since he was small, claims that amazake is ingrained in his daily life. We spoke with him to find out why he decided to promote amazake and the benefits of amazake he has uncovered in his exhaustive research.

Fujii began drinking amazake in third or fourth grade of elementary school. The amazake his mother made was so delicious that he became obsessed with it, to the point that he made his own.

“I fell in love with the taste and aroma of amazake. Nothing else could compare to its distinctive, koji-derived aroma and its slight, but not persistent, sweetness. I would get bored with off-the-shelf juices, but I never got tired of amazake. My parents stopped making it after a while, so I started making and drinking my own.”

Fujii went on to the Tokyo University of Agriculture, where he studied fermentation and brewing. Later, he took a researcher post at a health food company, where he was involved in the cultivation of lactic acid bacteria and yeast and in product development, which rekindled his passion for amazake.

“In university, I had a lot of opportunities to get amazake from a friend whose family owned a saké brewery, and when I started working, I would bring my homemade amazake to work for my colleagues to try. On business trips, I would buy amazake whenever I saw it, so I was always around amazake. Then, when amazake started trending around 2013 and the number of amazake products on the market increased, I got really interested in just how many types of amazake there are throughout Japan.”

Fujii, who describes himself as a person who, once he gets into something, goes all in, launched the amazake.com website in 2016 and began his activities as the Amazake Explorer, including sampling and reviewing amazake from across the country and gathering all kinds of amazake information.

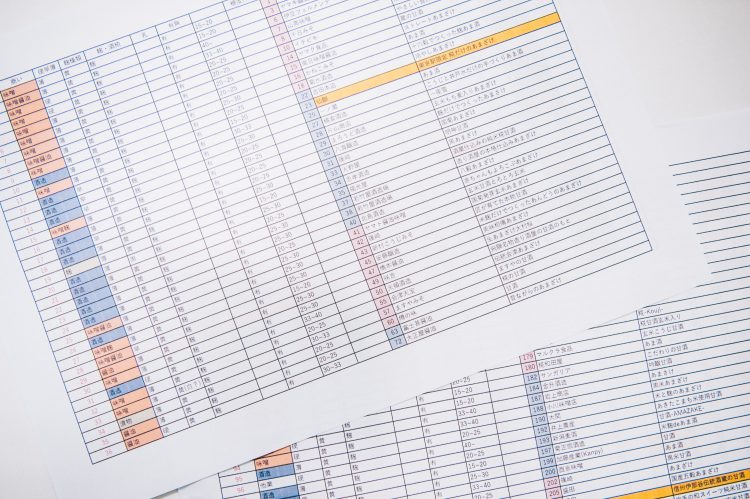

Part of Fujii’s database on amazake sold around the country that he has sampled. Each variety is listed with the type of producer, the variety of koji, the sugar content, tasting impressions, and other data.

Being a former researcher with a passion for experimentation, Fujii’s curiosity about amazake knows no bounds. Since he drinks amazake daily, he underwent exams to test his intestinal flora (the vast number of bacterial communities in the intestines) in order to understand the condition of his intestines.

▶See Fujii’s intestinal flora records here. [In Japanese]

“I’ve been interested in probiotics since university, because there were new discoveries and research going on, showing that, for example, changing the state of lactic acid bacteria in the intestines can change one’s constitution. From there, I got the idea of investigating what bacteria were in my intestines, as I drink amazake every day. The results showed that, compared to the average person, I had about four times as much beneficial intestinal bacteria (equol producing bacteria) that convert soybean isoflavone to equol, a substance that is easily absorbed by the body. Given these results, I plan to use data to track how my intestinal condition changes every year.”

As someone who researched lactic acid bacteria, Fujii is capable of examining amazake from the standpoint of probiotics.

Fujii also studies amazake through a cultural lens, investigating amazake-related festivals and events throughout the country.

“For example, there is a festival at the Kumano Shrine in Chichibu, Saitama, where participants wearing nothing but loincloths pour amazake over each other. Called the Inohana Amazake Festival, it is held in July when the wheat harvest gets underway to thank the gods for the wheat harvest and to wash away bad luck with amazake. At another distinctive festival called Ohitsuwari [literally, Rice-Tub Smashing Festival] at the Muro Shinmei-sha Shrine in Aichi, sekihan [so-called red rice made with glutinous rice and red beans] is stuffed into a rice tub (called an ohitsu), which is then covered with a lid. Men in their ‘unlucky’ yakudoshi years struggle over the ohitsu while being doused with amazake, smash the lid open with their bare hands, and eat the sekihan inside the tub together. There are many festivals and events featuring amazake like this all over Japan.”

Fujii participated the Ohitsuwari festival in October 2018. It appears he received the lid of the ohitsu tub.

There are more than 150 festivals throughout Japan that use amazake, ranging from those in which amazake plays a central role to those in which amazake is used as a goshinsen offering to the gods. Fujii gathers information like this from numerous references, local encyclopedias, and personal visits to the sites and publishes the information at amazake.com and on other media.

Fujii has personally sampled and reviewed over 360 varieties of amazake to date. His reviews consist of more than subjective tasting evaluations: he places importance on looking at products with objective data, such as measurements of their sugar content.

“Some amazake state on the label that they are best enjoyed mixed with water. I have looked into the threshold — that is, at what concentration this holds true — using sugar content data. If the product lists its ingredients, I’ll refer to it because the percentage of carbohydrates is almost equivalent to sugar content. If a product doesn’t list its ingredients, then I’ll measure its sugar concentration with a saccharimeter. In general, if the sugar concentration is over 25 percent, then it is likely a stronger type of amazake. It depends on the person, but this is a line above which most people find it easier to drink amazake as a mixed drink.”

Fujii’s saccharimeter. A small amount of amazake is placed in the top round hole to make the measurement.

Fujii also pays attention to the koji used to make amazake. He experiments trying different commercially available koji to see what kind of amazake they make.

“The koji used does change the taste of the amazake, but the biggest difference is due to the differences among producers. The way the ingredients are processed, the koji used, and the fermentation conditions are all different, which leads to the wide range of tastes.”

Saying “we also make these”, Fujii showed us some cookies made with squash and sweet potato amazake that he plans to market. The cookies are superb, with the addictive gentle sweetness that only amazake has.

“Not many sweets on the market contain amazake, so I tried making them. Amazake does not necessarily have to be made from rice. It can be made from nearly any vegetable that contains plenty of carbohydrates. Cookies and other sweets are easier to carry and promote than a bottle of amazake. That’s why I want to develop amazake as confectionaries.”

Fujii is also thinking about promoting Japanese amazake overseas.

“Amazake is made in countries outside of Japan, particular South Korea and China. In rainy Southeast Asian countries like the Philippines, the people traditionally make alcohols using mold that grows on grains. They drink an amazake-like drink extracted during this fermentation process. I’d like to explore these amazake from other countries as well.”

From drinking amazake and studying its history to experimenting with its ingredients, amazake has become an indispensable part of Fujii’s life.

“It’s important that fermentation culture, including amazake as well as miso and nukazuke [pickles made in rice bran], continues to be a part of daily life even in our present age. If these foods are no longer made, the culture will disappear. Amazake will continue to be an essential part of my life. As someone trying to preserve and expand this culture, I wouldn’t be very convincing if it wasn’t a part of my daily life. [laughs] My wish is that more people in Japan and other countries will integrate amazake and fermentation culture into their daily routines.”

The Amazake Explorer

The Amazake Explorer

Born in Tokyo in 1985, Fujii grew up in an environment where he ate fermented foods from an early age, such as pickles and miso made by his grandfather and amazake made by his mother. He later became interested in the microorganisms that produce fermented foods and enrolled in the Department of Fermentation Science at the Faculty of Applied Biosciences, Tokyo University of Agriculture. After graduating from the Tokyo University of Agriculture’s graduate school in 2013, he worked as a food researcher and began to devote himself to exploring amazake. Presently, as the Amazake Explorer, he reviews commercial amazake from around the country and works intently on making his own amazake.