Preserving Japanese Food Culture in Brazil

Jul 24,2025

Preserving Japanese Food Culture in Brazil

Jul 24,2025

Brazil, the largest country in South America and far from Japan, is home to many Japanese descendants.

Brazil, the largest country in South America and far from Japan, is home to many Japanese descendants.

Ohno Minaka is a graduate from the School of Integrated Health Sciences at the University of Tokyo’s Faculty of Medicine and completed a Master’s program in Food Science at the University of Copenhagen. She is currently conducting research on umami flavors as a research assistant in Denmark. In December 2024, she visited Brazil to observe and study the Japanese diaspora communities in the state of São Paulo. She was interested in finding out how traditional Japanese food culture has been preserved and adapted in Brazil, both in urban areas (specifically the Liberdade district of São Paulo, which is also known as Japantown) and in rural areas (at Comunidade Yuba, a self-sufficient farming cooperative). Ohno presents her observations in this report from Brazil.

During the Meiji period (1868 to 1912), Japan faced rapid population growth, land shortages, and worsening poverty, particularly in rural areas. To address these problems, the Japanese government encouraged some of its inhabitants to emigrate overseas. Meanwhile, Brazil’s coffee industry was growing at a fever pitch in the late 19th century, creating a massive demand for agricultural laborers. Given these circumstances, Japan and Brazil signed a migration treaty paving the way for Japanese workers to be accepted in Brazil.

Japanese immigration to Brazil officially began in 1908 when the first ship, the Kasato Maru, arrived at the port of Santos carrying 781 Japanese immigrants. By the end of World War II, approximately 240,000 Japanese had immigrated to Brazil, accounting for about 80 percent of all Japanese immigrants in South and Central America.

In the early going, many Japanese immigrants came to Brazil as temporary migrant workers, employed as contract laborers on coffee plantations. Over 95 percent of the immigrants worked in agriculture. Some grew Japanese vegetables and familiar crops, while others made koji malt as a way to recreate traditional Japanese food.

Their diet in those first years was extremely basic, centered on white rice, feijão (Brazil’s most common bean), dried jerky, and salted sardines. Unable to obtain miso or soy sauce, the immigrants began cultivating soybeans and making koji using koji mold they had brought with them from Japan. Eventually, they started making their own miso. In this process, tamari soy sauce [a dark and rich tasting soy sauce] was produced, enabling them to maintain a diet centered on rice, miso soup, and pickles.

The typical ingredients for traditional Japanese foods were difficult to obtain and expensive, so the immigrants used local ingredients and applied their ingenuity and creativity to come up with adaptations and substitutes.

●Soy sauce substitutes

Traditional tamari soy sauce was made by mixing caramelized sugar into liquid drained from miso barrels. Some people made soy sauce substitutes using feijão beans.

●Vegetable substitutes

Green papaya was consumed fresh, and chuchu (chayote) was dried and used to make pickles.

●Bean substitutes

Feijão beans served as a substitute for azuki beans in making sweet bean paste. They were also used in making miso and soy sauce.

●Starch substitutes

Cassava was made into dumplings or sun-dried and fried and eaten as so-called Okinawan senbei crackers. Cornmeal (fubá) was mixed with wheat flour for dumplings or used as the nuka [rice bran] for nuka-zuke [rice bran pickles].

●Pickled fruit substitutes

Green peaches were colored with beets or roselle to resemble umeboshi [pickled plums]. Salted roselle, called Brazilian plums or flower plums, also served as a substitute for umeboshi.

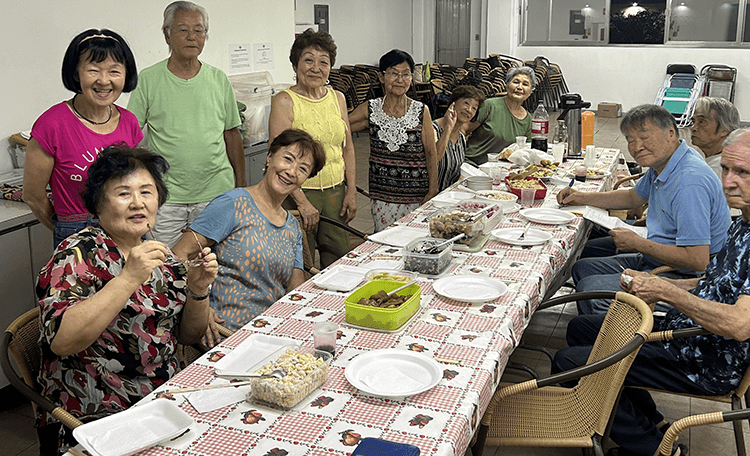

A gathering of Japanese descendants who brought such homemade cooking as simmered dishes, ohitashi boiled greens, and rice balls

Liberdade, a district adjacent to downtown São Paulo, is home to one of the world’s largest Japanese communities. The area is lined with hotels, Japanese restaurants, bookstores specializing in publications in Japanese, and Japanese-style souvenir shops operated by Japanese Brazilians. While the number of shops run by Chinese, Korean, and other Asian immigrants has increased in recent years, Japanese supermarkets in Liberdade carry nearly every Japanese ingredient you can think of — yuzu citrus, gobo [burdock root], konjac, tofu, natto [fermented soybeans], and more.

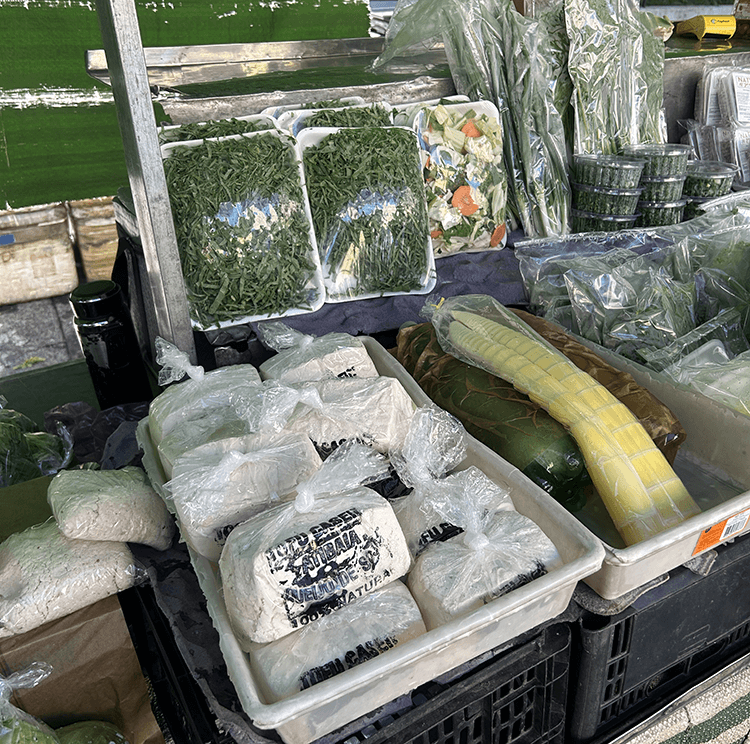

The Liberdade Farmers Market offers homemade items like tofu and natto

There are generally two groups of Japanese people in Liberdade. Those who moved from Japan to Brazil in their twenties for work and have lived here for over 20 years. And then the Nikkei [Japanese descendants] who were born and raised in Brazil in the households of Japanese descendants.

The writer (Ohno Minaka), during her time in Liberdade, stayed with a Japanese couple in their late 40s who moved to Brazil over 20 years ago. They work for a Japanese-language newspaper, live in the Japanese district, socialize with Japanese friends, and cook and eat Japanese food. Despite living in Brazil for over two decades, they speak almost no Portuguese. It truly felt like living in a microcosm of Japan on the other side of the world.

Residents of Comunidade Yuba range in age from one to 96

Colônia Aliança is a large permanent agricultural settlement established in 1924 in the municipality of Mirandópolis, in the northern part of São Paulo state, some 600 kilometers from São Paulo city. This settlement consists of three villages: First Aliança (Shinano Village), Second Aliança (Tottori Village), and Third Aliança (Toyama Village).

In the First Aliança, a group of young people led by Yuba Isamu established a unique Japanese community called Comunidade Yuba in 1935. This farming cooperative is home to 60 to 80 people of all ages and genders, living a self-sufficient lifestyle rooted in Japanese traditions, with a focus on agriculture, art, and communal living. The primary language of daily life is Japanese, though everyone also speaks Portuguese.

Every morning, a fire is started with bamboo and wood for boiling water and making soap

Meals at Comunidade Yuba follow a regimented schedule and are served at set times: breakfast at 6 a.m., lunch at noon, and dinner at 6 p.m. Fresh ingredients are used without waste and carefully prepared by the women in charge of the kitchen. Vegetables are harvested each morning at dawn and cooked that same day, maintaining the deep connection between the land and the food on Comunidade Yuba’s dining tables.

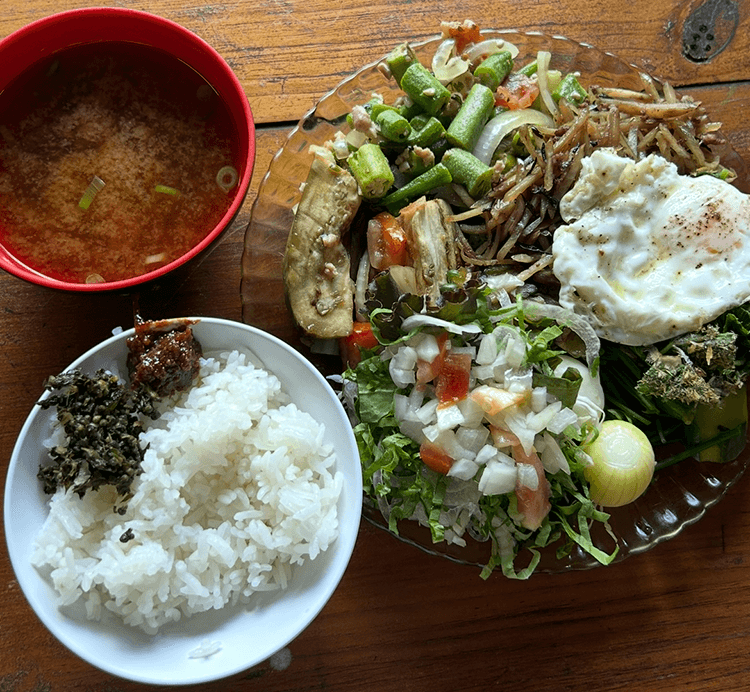

Lunch consists of rice, miso soup, salad, pickles, fried eggs, and simmered root vegetables

The food at Comunidade Yuba is comprised mainly of fresh, home-grown vegetables, always accompanied by rice and miso soup, along with various pickles like nuka-zuke, asa-zuke [lightly pickled vegetables], and umeboshi. The main dish varies daily, typically including stir-fried vegetables (with a small amount of chicken) or simmered dishes using dashi stock. Their daily diet follows a traditional plant-based pattern, heavy on vegetables and legumes, with only very small amounts of animal protein like chicken or pork. Viewed through the hare and ke [special occasions versus the everyday] lens, these are meals for ke [ordinary] days.

For hare days, such as when fish is caught or meat is received from neighbors, dishes like sashimi, fried fish, karaage [Japanese fried chicken], and tonkatsu [pork cutlet] appear on the tables. For special occasions like Christmas or New Year’s, meat-centered feasts, such as churrasco [Brazilian-style barbecue], are also served.

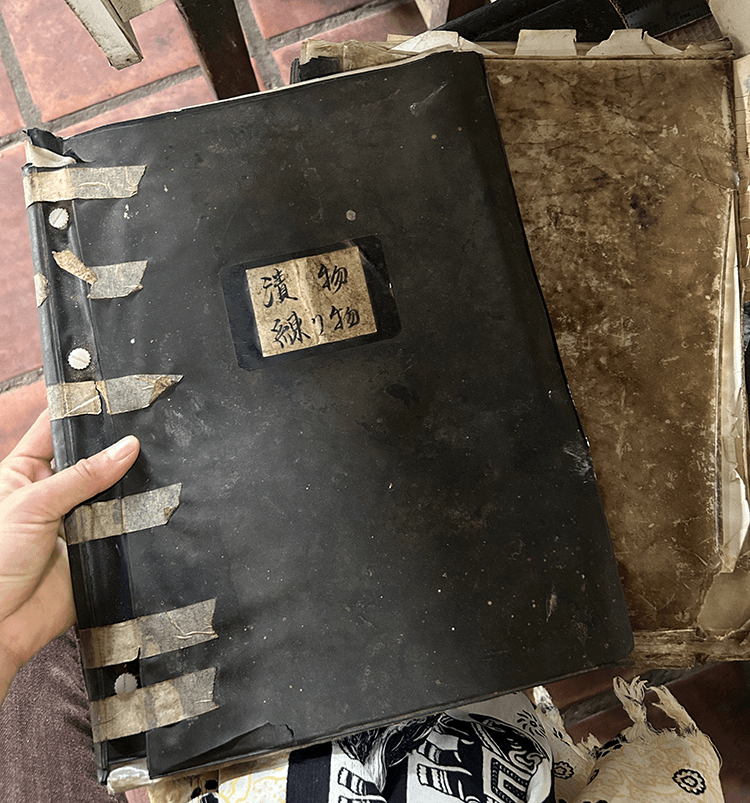

Most of the seasonings and preserved foods used at Comunidade Yuba are made from scratch based on recipes passed down through the generations. The women responsible for cooking learned their skills through oral traditions and written notes in old cookbooks. Basic seasonings and preserved foods like miso, soy sauce, koji, dashi powder, umeboshi, nuka-zuke, and natto — items readily available at any supermarket in Japan — are painstakingly and meticulously crafted at Comunidade Yuba.

A recipe book that has been handed down for more than 70 years at Comunidade Yuba. Generations of women have learned to cook with this book. The recipes recreate the flavors of the first settlers at Comunidade Yuba.

“When our mothers came to Brazil and started this cooperative, making everything themselves was simply the norm. It was the only way they had to preserve their food culture,” says Misa, a long-time cook at Comunidade Yuba.

Miso and soy sauce are indispensable to Japanese cooking and have been produced at Comunidade Yuba since the cooperative was first founded. Because Japanese cuisine is centered on rice and miso soup, rice and soybeans are, at once, both staple foods and base ingredients for seasonings. Comunidade Yuba, naturally, cultivates rice and soybeans.

This tane koji [seed koji] is rice koji used for miso, soy sauce, mirin rice wine, salted koji, and other seasonings

The koji mold necessary for fermentation begins with making tane koji, or seed koji. Koji is usually cultivated in the West in specialized environments with temperature and humidity controls. Comunidade Yuba, however, does not have such facilities, so it produces koji in keeping with Brazil’s uniquely hot and humid climate. To account for the local climate, Comunidade Yuba employs a two-stage process to make koji.

1. First, make the tane koji with koji spores.

2. Next, inoculate the rice koji using the prepared tane koji.

This two-stage process gradually acclimates the mold bacteria to the local climate. This careful method ensures a consistent fermentation process, allowing the residents to maintain their tradition of homemade seasonings while adapting to Brazil’s climate.

At Comunidade Yuba, miso is made using rice koji, boiled soybeans, and salt, just like in Japan. However, subtle adjustments are necessary depending on the climate and the type of rice used (Brazilian or Japanese).

The miso is made from rice koji, soybeans, and salt. It is used daily to make miso soup, stir-fries, simmered dishes, and other dishes.

“The ratio of soybeans to rice koji, the moisture content, the fermentation period … everything changes slightly depending on the climate and ingredients. I hole up in the room where the koji is prepared for five hours at a time, tending to it constantly. Koji is very delicate, so it requires continual attention. If it doesn’t go well, unwanted bacteria multiply, and the soybeans turn into natto instead of miso. I’ve failed many times, but gradually I’ve learned to understand it through the senses. It’s hard to explain, but it’s something you feel,” says Hyo, an expert miso and soy sauce maker.

After mixing the carefully prepared rice koji, boiled soybeans, and salt, the miso is fermented in wooden barrels for at least six months. The barrels were originally made in Brazil for winemaking and have been passed down for generations. Some are over 100 years old, passed down from Hyo’s mother.

The miso ferments in wooden barrels for at least six months

“For us, miso isn’t just a seasoning that adds umami. Miso contains the history of our lives. We live together with the koji mold. It represents so much more to us than a mere seasoning,” says Hyo.

During fermentation, the surface of the miso is protected by covering it with salt-boiled okara [tofu refuse], a byproduct of tofu production at Comunidade Yuba. Once completed, only miso that meets Hyo’s exacting taste standards is selected. It is then branded with the YUBA mark and sold in supermarkets across Brazil, as well as being used daily in Comunidade Yuba’s communal kitchen.

Comunidade Yuba’s miso products are sold under the YUBA brand in supermarkets

Producing soy sauce requires handmade rice koji, soybeans, and corn. The soy sauce is brewed for about three full months. The finished soy sauce is used daily in nearly every dish, including stir-fries, simmered dishes, and ohitashi.

Comunidade Yuba produces soy sauce with two different methods: Tamari soy sauce is a byproduct of miso production, while regular soy sauce is fermented from soybeans, corn, and salt. Since wheat, traditionally used in Japan, is not common in Brazil, corn is used instead.

For regular soy sauce production, boiled soybeans and roasted corn are mixed to make koji, then combined with salt and water and stirred daily. Fermentation takes at least six months.

This regular soy sauce is an essential seasoning in Comunidade Yuba’s daily cooking. Tamari soy sauce, on the other hand, has a richer, deeper flavor and is used in special dishes, such as when residents enjoy sashimi prepared from freshly caught fish.

When there is leftover koji, salted koji and amazake [a sweet drink made from koji] are made. Amazake is popular with everyone from the older generations to the kids. Enjoyed warm or cold, it’s a drink loved by all generations.

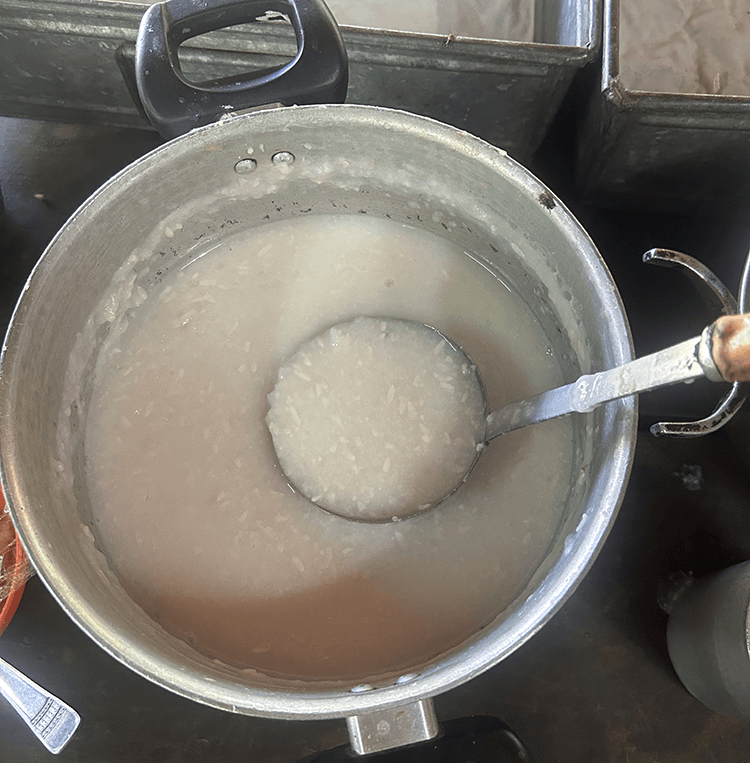

Amazake is made with rice koji and water and left for a day at room temperature

Salted koji is made with rice koji, salt, and water and left for a few days at room temperature

Dashi is an essential component of daily cooking at Comunidade Yuba, used in miso soup, simmered dishes, clear soups, and many other dishes. It is normally used in powdered form, with two types: dried shiitake mushroom dashi and dried sardine dashi.

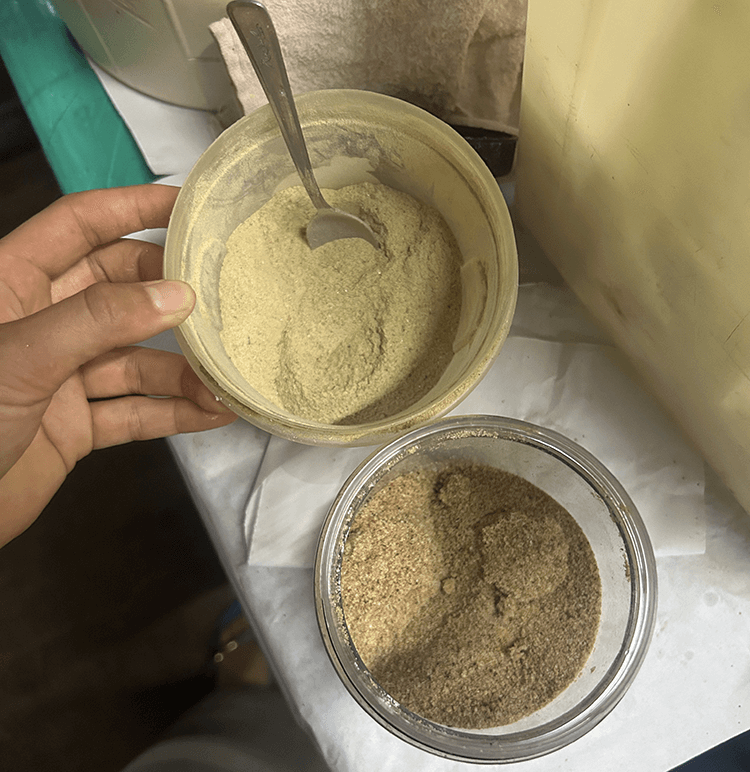

Shiitake dashi powder (top), and dried sardine dashi powder (bottom) imported from Japan

Dried shiitake are used in miso soup, clear soup, and various other dishes

The dried sardines are brought in from Japan and made into dashi powder. The shiitake, however, are grown at Comunidade Yuba. Tsuji is the mastermind behind the shiitake cultivation.

The two main ways to grow shiitake are log cultivation and sawdust substrate cultivation. Sawdust substrate cultivation (also known as artificial cultivation) uses blocks made from wood sawdust mixed with nutrients and can grow shiitake to maturity in a relatively short time. Log cultivation (natural cultivation), however, is a traditional method that grows shiitake in an environment more like the mushrooms’ natural habitat. Shiitake spores are inoculated into logs of broadleaf trees like the sawtooth oak or white oak, letting the mushrooms grow slowly at a natural pace.

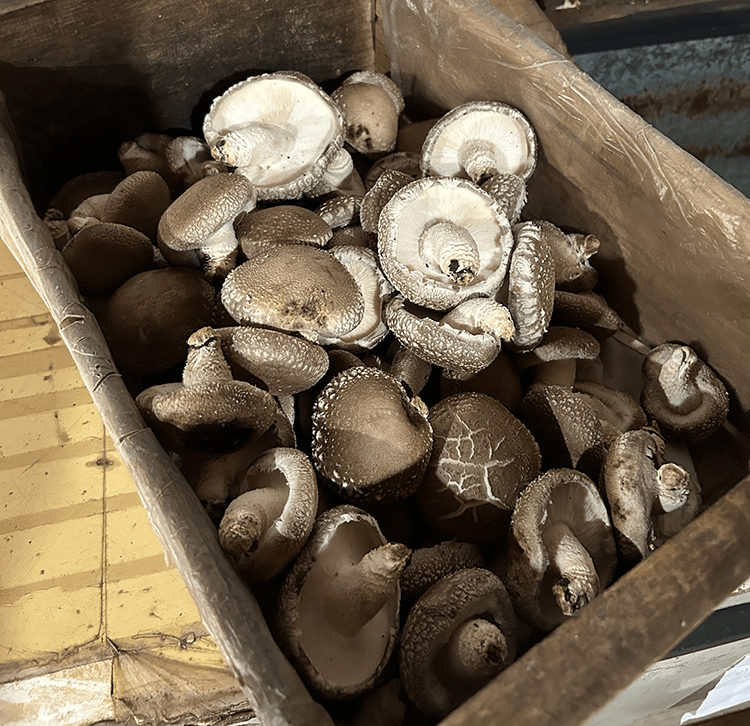

Shiitake grown on mango tree logs are used in cooking and are dried and made into dashi powder

Surprisingly, Comunidade Yuba grows their shiitake on mango tree logs. Tsuji, a shiitake cultivation producer, pioneered this innovative technique. He wondered whether the plentiful mango trees in the region could be used to grow shiitake. After much experimentation, he succeeded in growing shiitake on mango logs. Starting with just 20 logs in 1987, he spent over a decade improving his cultivation method, meticulously recording data from each harvest to refine his technique. He also built the shiitake house at Comunidade Yuba entirely with his own hands.

Tsuji’s life story is as unique as his shiitake cultivation technique. He originally worked as a radiological technician in Japan, but driven by a spirit of exploration, he cycled around Japan and then the world. He eventually wound up at Comunidade Yuba and became passionate about shiitake cultivation.

1. Harvest the mango logs

The mango trees are procured from an acquaintance’s field and cut into logs of a uniform length with a chainsaw. The log surfaces are cleaned and prepared for inoculation with shiitake spores.

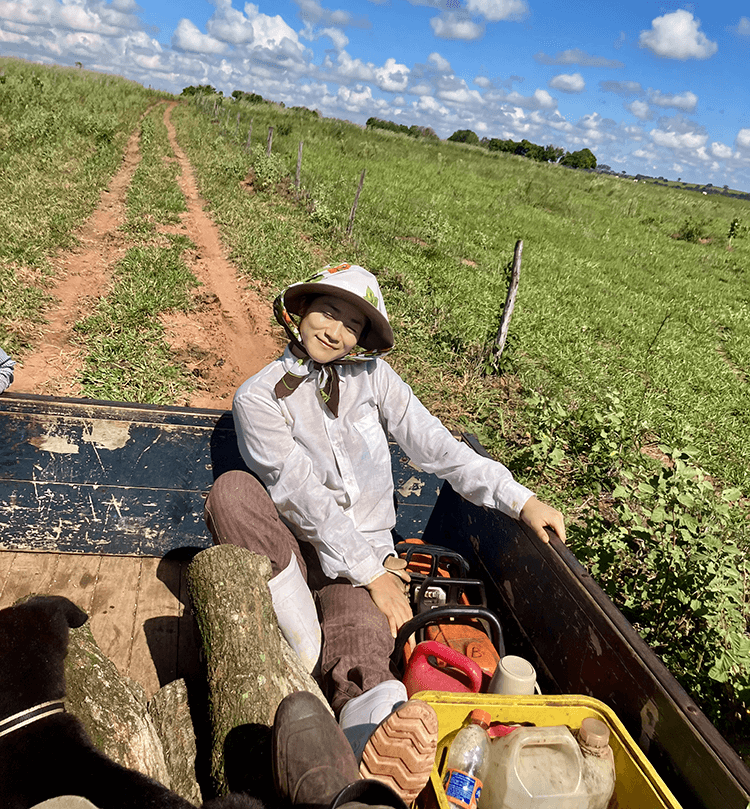

Returning with mango logs harvested from an acquaintance’s mango orchard

The logs are cut to length with a chainsaw

2. Inoculate the logs

Special shiitake spores are cultured on small wood chips and then embedded into the logs.

Shiitake spores are cultivated on small wood chips

3. Cultivate the spores (approximately six months)

Water is applied to the logs regularly while waiting for the spores to spread out inside the logs. Fine-tuning the humidity level requires professional-level skill. This cultivation process takes around six months, after which the logs become lighter. If you shave off the surface of the logs, you will start to smell the aroma of shiitake, which signals the logs are ready for germination.

“The logs can’t be too dry or too wet. You need to find the perfect balance, which you can only learn through failure and experience. There’s no standard or reference. You have to fail many times before you finally develop a feel for it,” says Tsuji.

The shiitake spores are cultivated on the logs for about six months while regularly being watered

4. Induce germination with a stimulus method

Once cultivation is complete, preparations for harvesting the mushrooms begin. To induce germination, the logs are subjected to a stimulus. This involves immersing them in cold icy water or striking them with a physical impact to replicate the stimulus of a natural thunderstorm. At Comunidade Yuba, ice water immersion is used to stimulate germination. About two days after the treatment, the shiitake germinate and are ready for harvest. Thick logs can be used for up to three harvests before being discarded.

Harvested shiitake waiting to be sold

For its nuka-zuke pickles, Comunidade Yuba uses rice bran produced when milling rice grown on the farm. Cucumbers are pickled when available.

Pickles are an indispensable part of daily meals at Comunidade Yuba. Several varieties are always on hand, typically including nuka-zuke, umeboshi, fukujin-zuke [sliced vegetables pickled in soy sauce], and vegetables pickled in salt. Because the pickles’ distinct textures and flavors enhance the taste of the rice, they are loved by both kids and adults to go with their rice.

So-called flower plums are roselle pickled in salt. They resemble umeboshi, but have no added red perilla.

Particularly noteworthy are the so-called flower plums. These pickles are made from roselle, a plant related to hibiscus. Since plums are hard to come by in Brazil, roselle came to be used as a substitute for plums to make pickles similar to umeboshi. Pickled in salt, flower plums closely resemble traditional umeboshi in both appearance and taste. Their robust sourness and saltiness, combined with a subtle floral aroma, create a unique and compelling flavor profile, even without the addition of red perilla.

In distant Brazil, ingenious adaptations of Japanese culinary culture, utilizing locally sourced ingredients, continue to thrive to this day.

An Aichi native born in 1999, Ohno graduated from the School of Integrated Health Sciences at the University of Tokyo’s Faculty of Medicine and completed a Master’s program in Food Science at the University of Copenhagen. She continues to reside in Denmark, conducting research on umami flavors as a research assistant. Her hobbies include yoga, and she is obsessed with brown rice and miso soup.