Home Brew Tips Inspired by Nordic Restaurants

Feb 03,2022

Home Brew Tips Inspired by Nordic Restaurants

Feb 03,2022

Nishizuka Tomoki is a self-confessed fermentation fanatic who is passionate about making fermented foods at home. He home-brews fermented seasonings rarely seen on store shelves, such as miso made from bread, yellow-pea soy sauce, and tomato vinegar.

For this article, we talked with Nishizuka about the fascination and difficulties of fermentation and his many homemade fermented seasonings.

More and more people today are enjoying making their own fermented foods at home. The fermented foods that Nishizuka crafts are a little out of the ordinary. For example, miso — a traditional Japanese provision — is generally made from soybeans, rice, or wheat. Nishizuka, however, makes miso from bread. What got Nishizuka into making fermented foods were fermentation recipes from the world-famous Danish restaurant Noma

“Noma was ranked as the world’s best restaurant five times by The World’s 50 Best Restaurants and in 2021 received a three-star rating from Michelin. The restaurant runs an independent in-house fermentation laboratory, where it continually researches and develops fermented foods. Northern Europe, with its long winters, has a deep-rooted culture of fermentation to preserve foodstuffs. Noma, however, has taken the Nordic fermentation culture to new places and stirred up a fermentation wave in the restaurant industry. Living in Japan, I was obviously very familiar with fermented foods like miso and soy sauce, but I had no particular interest in them. But when I heard about what Noma was doing with fermented foods, I felt the attraction of fermented foods, in a kind of reverse imported way, and I began thinking about making them myself. This is why the fermented foods I make are all based on Noma recipes.”

Nishizuka’s yellow-pea soy sauce

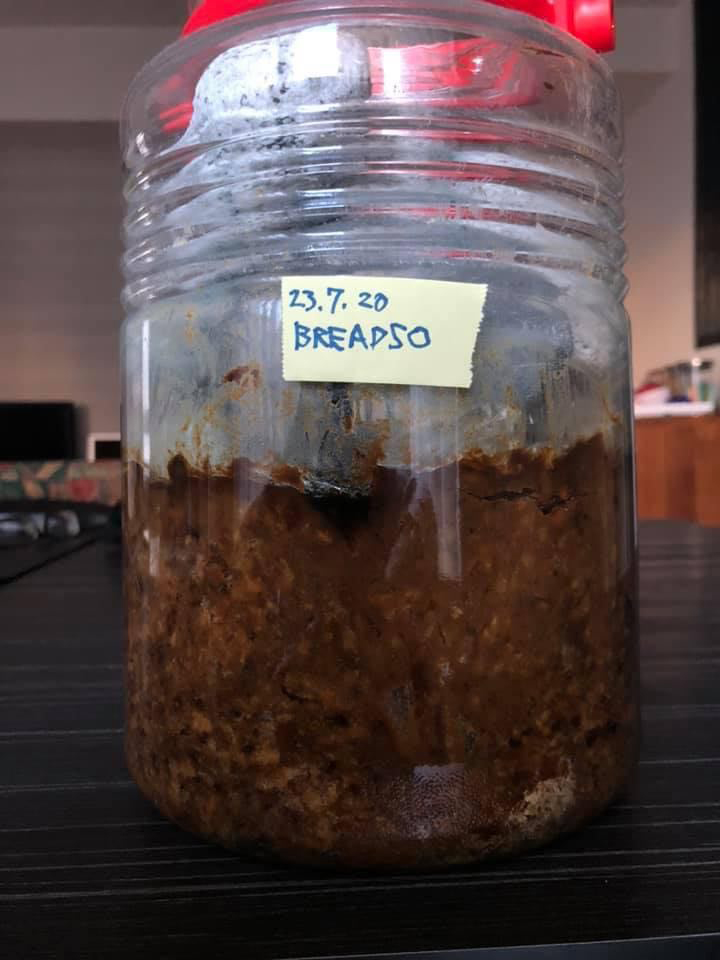

Nishizuka’s miso made from bread, on the surface, looks almost the same as ordinary miso. But when you taste it, a mild, faintly sweet flavor spreads throughout your mouth.

“I use a hard bread called pain de campagne to make my miso. I rip the bread into small bits, combine them with koji [rice malt], and adjust the amount of water so the mixture has the consistency of a miso ball. The remaining steps are the same as making ordinary miso. I spread the miso mix out to fit exactly in a storage container, weigh it down, and let it mature. The miso is still very sweet around the six-month mark, but after a year or so of aging, it develops a deep flavor and aroma.

“Bread is made up of finer particles, so the koji decomposition process is said to proceed more easily with bread than with soybeans or rice. This may explain why bread miso is so smooth to the palate. Soup made with this miso has a gentle, slightly viscous taste.

“I sometimes add yuzu citrus fruit during the process to make yuzu-flavored bread miso. I use the juice and finely chopped pulp from the yuzu, but you have to be very careful about balancing this with the water and koji or else it will turn moldy. It’s hard to get it right.”

Yuzu-flavored bread miso

Another aspect Nishizuka is particular about is making his own koji for use in making miso.

“I’m the type of person who, once I get started on something, isn’t satisfied until I’ve taken it all the way. I experimented with making koji around 15 times until I made some that I could live with.

“The most crucial thing about making koji is controlling the temperature and humidity. They are very simple factors, but they tripped me up many times in the beginning. The koji bacteria are very delicate. You need to pay close attention to the water absorption rate of the rice and the time. Only when you try it for yourself will you come to realize these things that you can’t learn from books and videos alone.”

Nishizuka is diligent about controlling the temperature and humidity

Nishizuka, in addition to miso, makes his own soy sauce, fish sauce, and vinegar. To make soy sauce, he uses yellow peas, which are commonly eaten in Northern Europe, India, and other places, instead of soybeans. The resulting soy sauce has less saltiness and a rich sweetness. The soy sauce is not pasteurized, which allows him to enjoy a milder and smoother aroma and flavor.

Fish sauce, made by fermenting fish, is a popular seasoning in Japan and countries around the world. The traditional process uses only raw fish and salt. Nishizuka, on the other hand, adds koji, which can accelerate and stabilize the fermentation process.

“I used yogurt makers to make fish sauce. I set the yogurt makers to the temperature at which the koji bacteria are most active. Sometimes I would have as many as five yogurt makers running day and night in my room for three months straight.”

Nishizuka has tried making homemade vinegar from many different ingredients, including lettuce, ginger, and butternut squash. But the most delicious of them all was tomato vinegar.

“I chop the tomatoes into chunks and blend them in a mixer and then add alcohol and acetic acid bacteria to ferment the tomatoes. I tested out two patterns after blending the tomatoes. In one, I strained out the pulp to get a clear liquid and in the other, I left the pulp in. As you would expect, the umami flavor of the vinegar fermented with the pulp left in was more complex and delicious.

“I ferment the vinegar for about three weeks while aerating it with an aquarium air pump, and then let it sit for several months afterward to allow the flavor to deepen. The taste is milder than ordinary vinegar and very fruity. It lacks the typical sharp acidity of vinegar even if you drink it on its own.”

A picture of the process of making butternut squash vinegar

Tomato vinegar

Nishizuka has been experimenting with homemade fermented foods for about two years now. But what is so interesting to him about making fermented foods?

“The most interesting thing is how fermentation produces flavors, aromas, and textures that are completely different from the original ingredients. Watching the ingredients ferment slowly over time, you get a sensation like you personally are being remade into something new.

“There is a depth to fermentation, a process in which your partners are microorganisms, that technique alone can’t master. That’s because there are aspects that are simply beyond human control, no matter how precisely you control the temperature and humidity or how well-honed your strategy is. For better or worse, you get a lot of unexpected results with fermentation. This ongoing struggle is what makes fermentation both intriguing and difficult.

“Right now, I’m just making the seasonings I feel like making. But for the future, I’m thinking of taking this beyond a hobby and exploring how to develop it into a business. Like craft beer made at a microbrewery, I’d like to offer unique, small-scale fermented seasonings.”

Nishizuka has worked in the restaurant industry for many years. He made a habit of following global restaurants as a way of studying other languages in relation to food. He got interested in fermentation after learning about the fermentation laboratory at Noma, a restaurant in Copenhagen, Denmark. He first started making fermented foods at home from kombucha and then moved on to miso, soy sauce, vinegar, fish sauce, kimchi, and other varieties. Nishizuka takes joy in being a purist about fermented foods, such as making his own koji to be used in his miso and soy sauce.