Maruya Hatcho Miso from Okazaki – Artisan Craft

Jun 05,2025

Maruya Hatcho Miso from Okazaki – Artisan Craft

Jun 05,2025

History buffs likely immediately recognize the name Okazaki, Aichi. Eight cho (870 meters) west of Okazaki Castle, the birthplace of Tokugawa Ieyasu — the first shogun of the Tokugawa shogunate, lies Hatcho-mura (now incorporated in the city of Okazaki as Hatcho-cho), which is home to two miso breweries. One of these is Maruya Hatcho Miso. We spoke with Asai Shintaro, president of Maruya Hatcho Miso, which was founded in 1337 and continues to make miso using traditional methods passed down since the Edo period (1603 to 1868).

Although hatcho miso is one of the most widely known Tokai region seasonings, it’s somewhat surprising to find out that only two miso breweries in the Hatcho area still produce hatcho miso using Edo-period brewing methods.

The difference between soybean miso produced in the Tokai region and hatcho miso made with traditional methods lies in the size of the soybean koji malt and its moisture content. The soybean koji used to make hatcho miso is larger with lower moisture content than that used to make soybean miso. This is why stones are stacked in a cone shape on top of the vats to apply pressure on the miso as it ferments and ages.

As we were guided into the warehouse and were struck by the enormity of the wooden vats and the stacked stones before us, president Asai Shintaro explained how hatcho miso is made.

“Each wooden vat contains six tons of miso, with about three tons of stones stacked on top. The stacked stones force the ingredients in the vat to circulate. Regular soybean miso has enough moisture that you only need to lay the stones flat on top. But hatcho miso has less moisture content, so we have to weigh it down with stones equivalent to about half the miso’s weight. That’s why we stack them this way.”

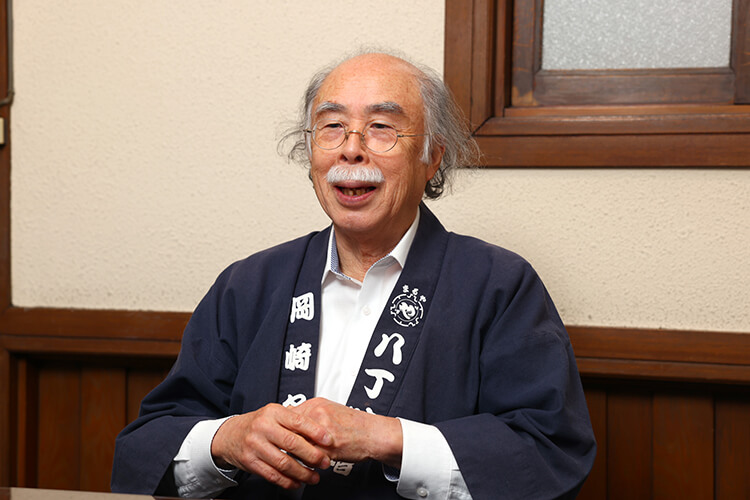

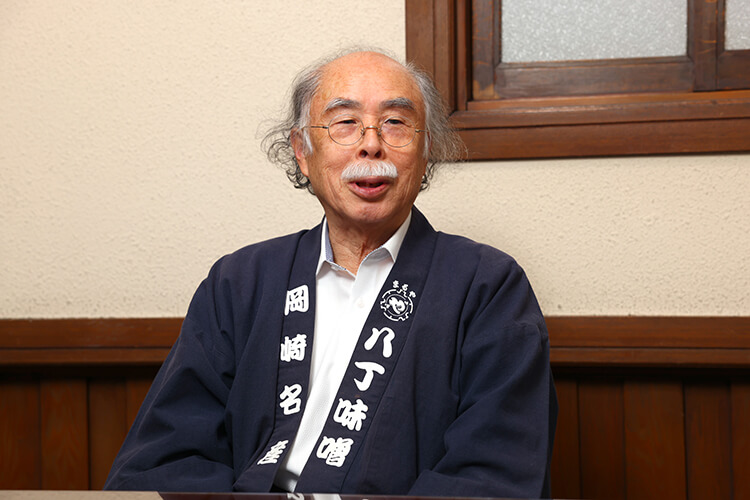

Asai Shintaro, president of Maruya Hatcho Miso

Once the stones are stacked, the miso is left to age for more than two years — at least two summers and two winters. We couldn’t help but ask if any of the stones ever roll off a pile. Asai’s answer: Not once so far. Stacking the stones requires skill and experience and is performed by workers who have learned the trade from the previous generations. It takes about ten years to become a fully skilled stone-stacker.

Asai has been recognized by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare as a Contemporary Master Craftsman (Gendai no Meiko) for his skill and knowledge of brewing hatcho miso

“The mixture of ingredients in the vats is arranged in three layers and is intentionally packed unevenly. Placing heavy stones on top promotes natural circulation within the vats. When the stones are stacked such that they apply pressure perfectly evenly, the flavor will end up being consistent throughout the vat, with no differences between miso at the top and at the bottom. Over the two years, lactic acid bacteria activity removes the sharp saltiness, resulting in hatcho miso with a mellow, cheese-like taste and umami flavor.”

When removing the finished miso from the wooden vats, they avoid machinery, digging it out by hand. “A shovel works best,” Asai says with a wink. “That’s how we’ve done it for generations.” Fermented in wooden vats under the pressure of hand-stacked stones, brewed naturally with the help of bacteria, and dug out laboriously. This is how Maruya has consistently delivered its enduring miso flavor.

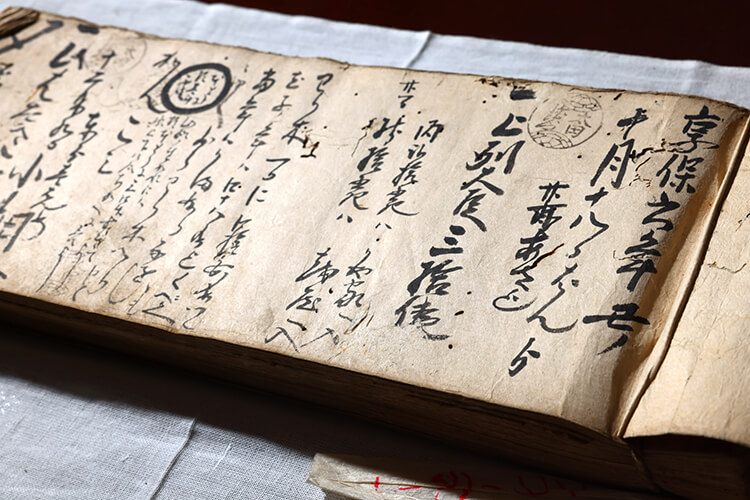

A miso brewing logbook from the Edo period. Records are kept each year listing the timing of operations, the amount of ingredients, and other details. Maruya continues to keep meticulous records to this day. “I feel like I have to record our work, as I’ve been entrusted with my part in this history,” says Asai. The brewing logbooks are passed along like a baton in a relay race, from predecessors to the present and then to the next generation.

Asai insists that traditional brewing methods are incompatible with mass production.

“Staying true to our method means we can’t produce miso in large quantities. But we are fine with that. We leave the production of mass-market miso to companies that can do it. We do, however, believe this brewery has its own role to play.”

The focal point of their efforts, explains Asai, is fostering an environment where the lactic acid bacteria can thrive. They don’t introduce any lactic acid bacteria from outside or cultivate specific strains. Rather, they ensure the bacteria already present in the brewery can flourish. To this end, they don’t use detergents even when cleaning the brewery, the wooden vats, and other equipment. Despite this, the place is kept remarkably clean. “I believe it’s because we constantly strive for cleanliness, and the microorganisms reciprocate in kind,” Asai says with a smile. Asai believes that maintaining a cheerful and upbeat atmosphere in the workplace influences the quality of what they produce.

“That’s why my policy is to never lay off any employees. This lets people work feeling secure, without unnecessary worries. The bacteria pick up on that sense of security and reassurance, and it affects the finished product. That, I believe, is what defines our quality.”

The wooden vats after being thoroughly washed and left to dry. The names of the craftsman who built the vats are written on the bottom.

Maruya could not brew its miso without its large wooden vats.

Maruya has carefully used and patched up its wooden vats for decades. Around 20 years ago, they put in an order with Fujii Seiokesho, a company in Sakai, Osaka, to have some new wooden vats made, but the company turned them down. The wooden vats needed to make hatcho miso must be not only large but also able to withstand the weight of three tons of stones stacked on top. The company said it had no experience making such barrels and was planning to shut down operations anyway by 2015.

“But I pleaded with the company to find a way. Losing the craftsmen and the tools to make the barrels would be a grave problem for us. I made a promise to order three barrels every year, and they have continued making them for us ever since.”

“At the end of the day, craftsmen want to be told that they are needed,” Asai says with a grin. “When they hear they are necessary, they’ll respond.” Today, operators of saké, soy sauce, and other breweries also order wooden vats from Fujii Seiokesho. And successors are emerging to take the place of the older barrel makers. Asai says he’s glad if he had any part to play in the revival of the barrel-making trade.

“We’ve lost so much in so many fields — culture, art, scholarship. What’s worse is we don’t realize it’s disappearing until it’s gone. Later, we think, ‘Damn. Why did we let it disappear?’ But once it’s gone, it’s too late.”

It’s this sentiment that drives Asai to preserve the good things passed on to us from previous generations.

Hatcho miso is made solely from Mikawa soybeans and salt

Asai, however, isn’t focused just on preserving and protecting traditions. Since the 1980s, when “organic” was not yet a common term, he has been dedicated to producing hatcho miso with organic soybeans. He has also undertaken numerous endeavors, such as expanding the company’s sales channels overseas. Today, Maruya miso is exported to 20 countries around the world. He says his own experiences have greatly impacted his decisions.

“When I was young, I got a job for a time, but I grew to hate it and jumped ship to study in Germany. During that time, I encountered Germans living calm, modest lives, and I thought that such a lifestyle suited me and felt right. While in Germany, I also found out about the concept of organic food and the people who aspire to a diet that would later become known as macrobiotics.”

Maruya’s shop sees many overseas visitors

Today, Maruya Hatcho Miso is loved by people around the world, especially those seeking macrobiotic diets or choosing gluten-free foods. Asai explains that this appreciation stems not only from the careful selection of ingredients but also from the simple, meticulous production process.

“I’ll soon be heading to Europe with our latest product, Miso Powder, a powder with the flavor of hatcho miso. This time, I plan to concentrate on meeting with European restauranteurs. This powder tastes excellent even when sprinkled on ice cream or steak. I hope to have productive meetings with people who are interested in my pitch.”

Miso Powder is designed to provide a hatcho miso accent to all kinds of dishes

We were left with a strong impression by Asai, as he spoke with a boyish, breathless excitement about his twin passions: continuing the traditions passed down from his predecessors, and looking forward to new encounters with people who click with Maruya’s spirit and the products it crafts.

For inquiries about brewery tours