The Umami of Kelp Dashi: Unveiling Regional Flavors

Feb 14,2017

The Umami of Kelp Dashi: Unveiling Regional Flavors

Feb 14,2017

The word dashi comes from nidashi-jiru [simmered soup stock]. Dashi stock is made by dissolving in water the umami flavor components of kelp, dried bonito or other fish flakes, dried sardines, dried vegetables (such as dried shiitake mushrooms or soybeans), or other ingredients. In this article, food researcher Kubo Kanako tells all about kelp-based dashi, one of the many types of dashi.

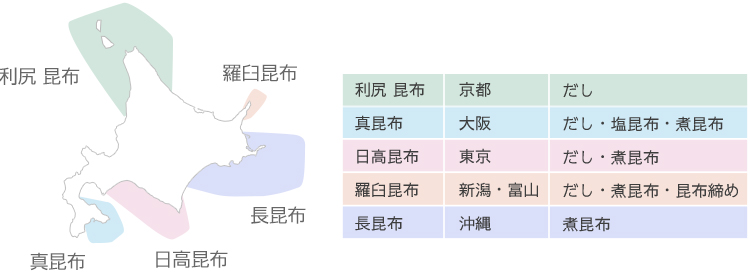

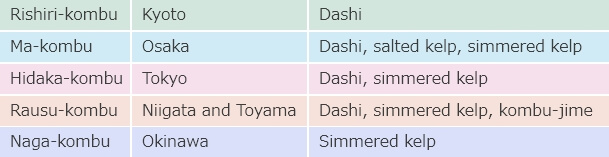

“There are many species of kelp [kombu in Japanese]: some of the main ones are rishiri-kombu, ma-kombu, and hidaka-kombu as well as rausu-kombu and naga-kombu. Kelp is primarily harvested in various coastal regions of Hokkaido.”

In general, rishiri-kombu dashi is clear, free of any particular tastes, and has a refined flavor with a hint of sweetness. It is favored by Kyoto’s high-end ryotei Japanese restaurants. Dashi made from ma-kombu is characterized by its very pale color and refined taste. Besides dashi, ma-kombu is also used for high-grade tsukudani kelp [kelp simmered in sweetened soy sauce] and salted kelp and it is often used in the Kansai region, particularly Osaka. Hidaka-kombu is distinctive for its smooth flavor. It is regularly used in the Kanto region and farther north, and its soft fibers make it well suited for kelp rolls, tsukudani, oden stews, and other simmered kelp dishes. Rausu-kombu is noteworthy for its soft fibers and makes a rich, strong-tasting dashi, although it tends to become a bit cloudy. It is suitable for daily use in miso soup and richer-tasting simmered dishes. Because of its broad shape, rausu-kombu is also found in kelp rolls and kombu-jime [kelp leaves for curing vegetables and fish]. Naga-kombu is not suitable for dashi, but it can be eaten as kelp rolls, in simmered dishes, and in salads. Naga-kombu is most often consumed in Okinawa and is used in stir-fries because it pairs well with pork.

“Each region tends to favor a certain type of kelp, and the type of kelp is closely tied to the region’s cuisine.”

Rishiri-kombu, Ma-kombu, Rausu-kombu, Hidaka-kombu, and Naga-kombu

▲Taste, aroma, and color vary depending on the type of kelp. The color of the dashi has no relation to its taste.

“In Kyoto, people prefer dashi made from rishiri-kombu; in Osaka, ma-kombu; in Tokyo, hidaka-kombu; and in Niigata and Toyama, rausu-kombu. As an experiment, people were asked which dashi they preferred based on just the taste and aroma, with the name of the kelp hidden. Test-takers were very likely to choose the kelp most often used in their home region. The results indicate people tend to prefer flavors that are familiar to their taste buds.”

Although most kelp comes from Hokkaido and is shipped throughout the country, the fact that different regions prefer different types of kelp can be attributed to kelp distribution during the Edo period (1603 to 1868). From the Edo period until the middle of the Meiji period (1868 to 1912), cargo ships plying their trade along the kitamae-bune route made their living buying, transporting, and selling foodstuffs and other products from Hokkaido and the Sea of Japan. Kelp harvested in Hokkaido made its way from Etchu (present-day Toyama) and Tsuruga (Fukui) via Omi merchants across Lake Biwa to Kyoto and through the Seto Inland Sea to Osaka, which was the nation’s center of trade and economy at the time. Although routes changed over time, kelp was transported by kitamae-bune cargo ships to Edo (present-day Tokyo), Satsuma (present-day Kagoshima), and Ryukyu (present-day Okinawa). It is believed that during this history, the variety of kelp matching local preferences became embedded in local cuisine.

“The built-up areas of Kyoto far from the sea were not blessed with fresh fish. On the other hand, Kyoto has delicious vegetables and other native ingredients, so the locals may have preferred rishiri-kombu because its mild flavor enhances the taste of vegetables. Osaka, however, is close to a port and has an abundance of fish. This is why ma-kombu, which goes well with fish, was probably preferred there. As for Tokyo, because it was at the very end of the kitamae-bune shipping route, it was likely easiest for people to obtain hidaka-kombu, which was produced in large qualities. Many people from Niigata and Toyama settled in Rausu, Hokkaido, and sent back rausu-kombu to their relatives, which is why this variety of kelp is often used in Niigata and Toyama. In the Hokuriku region, cuisine such as kelp rolls and kombu-jime developed out of the characteristics of rausu-kombu, and these are still enjoyed today as local delicacies.”

Rausu-kombu, Naga-kombu, Hidaka-kombu, Ma-kombu, Rishiri-kombu

▲Major kelp producing areas (left) and kelp preferences and uses by region (right)

“You can prepare dashi stock from dried bonito flakes, dried sardines, and many other ingredients. But of all these, kelp is the foundation of deliciousness. Once you understand the characteristics of kelp, you can definitely make good use of it.”

Kubo said that anyone can make dashi from kelp, since all you have to do is soak it in water to create a delicious stock.

“In the past, it was considered best to remove the kelp from the water just before boiling, but in recent years, research has shown that simmering kelp in lukewarm water at 60°C for one hour produces the best tasting broth. At home, however, it’s not so easy to maintain water at a steady 60°C. This is why I recommend first soaking the kelp in water for a longer period of time and then heating it in a pot to gradually increase its temperature at a low to medium heat instead of rapidly bringing it to a boil. Doing it this way keeps the kelp for longer in a state where the most broth is given off, making it possible to get a delicious dashi. I also recommend that people measure kelp by weight, not by length in centimeters. You cannot compare the amount of kelp accurately by length, since its thickness and weight varies by the kelp’s type and section.”

Kubo also said that once you understand the umami components of dashi, you can adjust for them and make even better tasting dishes.

“The umami component of kelp is glutamic acid. Dashi made from animal protein, such as dried bonito flakes, dried sardines, and meat, mostly contains inosinic acid, while dried shiitake and other mushrooms contribute guanylic acid and shellfish contribute succinic acid. Of these components, the glutamic acid in kelp creates a flavorful synergistic effect when combined with other umami components. This is why ichiban dashi (first brewing) and niban dashi (second brewing), which combine broths made from kelp and dried bonito flakes, are considered some of the most delicious dashi.” Kubo contends that a good ratio when combining kelp and dried bonito flakes is 15 grams of kelp and 25 grams of dried bonito flakes per liter of water.

“For one liter of water, I recommend using at least 30 grams of dashi ingredients.”

Kelp dashi can be combined with dashi made with dried shiitake mushroom (guanylic acid) or dashi made with shellfish (succinic acid), such as short-necked or freshwater clams, without clashing, resulting in a taste that is more than its constituent elements. On the other hand, dashi made with bonito flakes (inosinic acid) may produce too strong a flavor, depending on the combination even with ingredients like sea bream with the same inosinic acid, or clash with the flavors of ingredients like the common clam with succinic acid. In this sense, kelp dashi is very all-purpose.

“Even if you don’t have time to prepare dashi with kelp and dried bonito flakes when making a simmered dish, you can add some kelp to the pot before heating and slowly heat the dish to add more umami flavor. Especially if you are using chicken in the dish, the chicken’s inosinic acid and the kelp’s glutamic acid will combine and create a very tasty simmered dish.”

Kelp is said to be the foundation of deliciousness because it goes well with any ingredient and can, depending on the combination, boost the umami multiple times over. Kubo told us that she hopes people will try adding a piece of kelp to various dishes without overthinking it and discover just how easy and how richly flavored kelp is.

Culinary Researcher

Culinary Researcher

Growing increasingly interested in cooking, Kubo Kanako studied at the long-established Kyoto ryotei (high-class Japanese restaurant) Tankuma Kitamise from the time she was a high school student. After graduating from the Department of English at Doshisha University, she entered the Tsuji Culinary Institute, where she obtained chef’s and fugu (puffer fish) cooking licenses. Following a stint in the Tsuji Culinary Institute’s publications arm, she edited cook books at a publishing house in Tokyo, before going independent.

Today, Kubo is actively involved in a variety of culinary-related endeavors, including culinary production, styling, restaurant menu development, table decorating, editing and more.

She is the author of several works in Japanese, including Utsukushii morituske no kihon [Basics of Beautiful Plating] (Seibido Shuppan), Utsukushii ichiju nisai: “Oishii” to “kirei” in ha wake ga aru [Beautiful Soup and Two Dishes: There are Reasons for “Deliciousness” and “Beauty”] (Kawade Shobo Shinsha), Kichinto, yasai no kobachi chotto shita kotsu de “mō ippin” ga gutto oishikunaru! [Small Vegetable Side Dishes: Little Tips that Make That Extra Something So Much More Delicious] (Kawade Shobo Shinsha), Kichinto, oishii mukashinagara no ryōri [Delicious Old-Time Cooking] and Shun no aji techō aki to fuyu [Seasonal Flavor Handbook: Fall and Winter] (both Seibido Shuppan)

No.1

No.2

No.3

No.4

No.5