Edo Dietary Therapy: Insights from Novelist Ukiyo Kuruma

Mar 21,2024

Edo Dietary Therapy: Insights from Novelist Ukiyo Kuruma

Mar 21,2024

Kuruma Ukiyo has written numerous novels set in the Edo period (1603 to 1868) as well as essays and research papers on the Edo period. She also gives lectures and provides editorial assistance on Edo culture. With her deep knowledge of Edo’s food culture and dietary habits, she has penned such books as The Healing Foods of the Edoites and Simple Healthy Recipes Made with Fermented Food. We spoke with her for this article about the food culture of people during the Edo period and their relationship with fermented foods.

We arrive at a condominium apartment. Kuruma Ukiyo opens the door, saying “Please, come in”. Stretching out before us is a kitchen that gives the sensation of stepping back in time to the Edo period. Ukiyo had just finished creating this kitchen studio with an Edo theme, which she plans to use for workshops on Edo cuisine and for video shoots. While writing works set in the Edo period, she began getting involved in promoting Edo food culture. Although her adoration for all things Edo is unbounded, she admits she was born and raised in Osaka. Which begs the question: How does a former art director at an Osaka printing company become infatuated with Edo culture? Ukiyo begins by telling us how she was introduced to Edo culture.

“What got me hooked on Edo culture was ukiyo-e [a genre of Japanese art that flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries]. At the printing firm where I worked at the time, I oversaw all the printing operations for a certain department store. One day, I visited the department store’s art gallery to take in an exhibition of ukiyo-e. It was a big affair, and they even brought in woodblock printers from Tokyo to demonstrate the techniques of ukiyo-e. This is where I learned that Edo period publishers planned ukiyo-e projects and then commissioned painters and woodblock printers to make the art, which would then be bound and sold. I was very surprised that the same process as modern publications was already in place back then. I also felt a connection with my own work at the time and quickly became more and more interested in the culture of the Edo period.”

Since that exhibition, as she viewed numerous ukiyo-e prints and paintings, she found herself drawn to their beauty and the refinement of the craft. And as she developed favorite ukiyo-e artists and works, she became interested not only in ukiyo-e, but also in Edo culture more broadly.

As her relationship with Edo grew, she became particularly knowledgeable about Edo cuisine.

“I was once taught that Edo cuisine is about cooking seasonal ingredients with little fuss and bother. It made sense to me when I heard this. In a time before refrigerators, people’s basic approach was to buy freshly picked produce and ingredients and consume them on the same day. Later on, they developed preservation methods such as drying and fermentation. Seasonings and other techniques that evolved during the Edo period also played a major role.”

The fermented seasonings of Japan that readily come to mind are soy sauce, miso, and vinegar. Other seasonings, like dashi stock, saké, and mirin rice wine, were also already essential to cooking in the Edo period.

“Even though Japan is such a hot and humid country, the people here love to eat uncooked food. I feel many of Japan’s seasonings bring out the flavors of ingredients more than color them. I think soy sauce, vinegar, dashi, saké, and others were created to enhance the natural flavors of food. Of course, we must take due care about cleanliness and hygiene when eating uncooked food. But I suspect the emphasis on eating uncooked food helped these Japanese seasonings to flourish.”

Kuruma Ukiyo has written many books on Edo food culture

The Edo period continued for some 260 years, and according to Ukiyo, dark soy sauce only became available to the general population in the middle part of the Edo period. In the early years of the Edo period, light soy sauce was brought in from the Kansai region, but it was expensive to transport, putting it out of the reach of ordinary people. For this reason, the basic flavoring used by Edoites at the time was salty, consisting of salt and miso. Also, irizake, a type of home-crafted seasoning made by boiling down umeboshi plums, dried bonito flakes, and saké, was used in everyday cooking. Eventually, a soy sauce maker from Wakayama prefecture moved to Choshi, which is now Chiba prefecture, and began making soy sauce there. Many people in Edo engaged in heavy physical labor, so they preferred darker soy sauce than the soy sauce from Kansai. This led to the rapid spread of dark soy sauce.

“Because the water was different in Edo from that in Kyoto and Osaka, a culture developed of using dashi made from dried bonito flakes rather than kelp. Dark soy sauce also paired better with dashi made from dried bonito flakes. Dishes that we today think of as side dishes, such as kinpira gobo [sautéed and simmered burdock root], nishime [a vegetable dish simmered in soy sauce until the liquid is almost gone], and okara [tofu pulp], became the tastes of ordinary people’s Edo cooking thanks to the availability of dark soy sauce.

“Another thing is that it was in the Edo period that people began to truly enjoy eating, as in prior times they were continually at war. Food stalls lined the streets, restaurants were established, and a culture of dining out emerged. And as the cost of lamp oil came down, people were able to stay up later into the night, and it was an era when people began eating three meals a day instead of just two. In this developing food culture, we begin to see people enjoying soba, eel, sushi, tempura, and other more refined foods.”

The side dishes and cooking that emerged in this time later spread across the country and became firmly embedded in our lives. As a result, the term Edo cuisine fell out of use and today is rarely heard anymore.

Ukiyo refers to food from the Edo period as healing food. As she explained why, we got a glimpse into the daily lives of people in Edo.

“Oils were not commonly used in the Edo period because they were expensive and because people were terrified of fires breaking out. Sugar wasn’t used much either, as it was an expensive condiment for regular folk. And because they weren’t allowed to eat the meat of animals, they generally ate simple meals consisting of seafood or poultry. In other words, they abstained from ingredients and foods that lead to metabolic diseases. In addition, as I said before, they used fermented seasonings like soy sauce, vinegar, and miso. And preserves made by drying or fermenting ingredients almost always have higher nutritional value than their raw counterparts. The people of Edo ate these foods without being that aware of these benefits, but these foods led to stronger immunity and took care of their health.”

The fact that they were able to get fresh vegetables and fish every day is another reason why Ukiyo calls the food of the Edo period healing food.

“Vendors called botefuri who sold fish and green vegetables that they carried on shoulder poles came to the town every day. Natto [fermented soybeans] was one of the ingredients they would always bring to sell in the mornings. So much so that the saying developed: There may be days when the crows don’t caw in Edo, but there’s never a day when the natto peddlers don’t come. The bucket on one end of their shoulder pole would contain natto with whole soybeans and the other bucket would contain natto made from ground soybeans. The natto with whole soybeans was eaten as is, while the natto made from ground soybeans would be used in miso soup. Botefuri would bring chopped green onions and other condiments in a box as well, so people would wait for the natto vendors to come around as they went about their morning preparations and they would arrange the freshly-bought natto on their breakfast trays.”

Natto soup, made by adding ground natto to miso soup, was a standard breakfast item in the Edo period. Definitely try making it, as it’s easy and delicious.

The culture of eating natto for breakfast, which is very common for us today, had already begun in the Edo period. Ukiyo believes that it was probably only in the town of Edo that natto vendors came in the mornings. People in Kyoto and Osaka at the time ate shiokara [salty and spicy] natto (Daitokuji natto) instead of the sticky types of natto. This history is why still today people in eastern Japan tend to prefer natto more than people in western Japan.

The people of Edo, who maintained their health through their diet in a very natural way, were well aware at the time that miso was a healthy food.

“The people of Edo left us with such proverbs as ‘One bowl of miso soup gives you the power to walk three li [12 km]’ and ‘Miso keeps the doctor away’. The early Edo period doctor Hitomi Hitsudai, in his treatise on food and herbal medicine titled Honcho Shokkan [Encyclopedia of Food in Japan], wrote the following in the section about miso: ‘The sweetness and warmth of soybeans soothes the spirit, opens up the stomach, and improves the circulation of blood to expel various poisons from the body.’ We have other contemporaneous writings about the positive impact of miso on health, which leads us to believe that people in the Edo period had a good understanding that one soup and one dish — i.e., rice and miso soup — was a healthy meal.”

Since miso flavors vary by region, what kind of miso did the people of Edo use to make miso soup?

“Miso was made at home, with each household having its signature temae miso taste. The problem was that the land of Edo, which Tokugawa Ieyasu had placed at the center of his national unification project, was full of swamps. The men of the village were roped into the arduous work of draining the swamps and developing the land, which meant they had no time to prepare miso, and there weren’t enough women to do the work either. For this reason, the population bought their miso from places like Shinshu (now Nagano prefecture). Ieyasu, however, felt that these purchases of miso were a waste of money and urged people to make miso in Edo. He is said to have requested that people use plenty of koji [rice malt] to ferment the miso as quickly as possible and that the miso should have a flavor that was a mix of the red miso of Mikawa (today, part of Aichi prefecture) and the sweetness of Kyoto’s white miso. The result was Edo sweet miso that had a sweetness like that of dengaku miso [sweet miso paste made with sugar and mirin rice wine]. The people of Edo, many of whom engaged in heavy physical labor, received this sweet and spicy miso well, making it Edo’s homegrown miso.”

Just a taste of Edo sweet miso, and the sweet and spicy flavor will bloom throughout your mouth. It’s excellent in miso soup, as you would expect, but also delicious when eaten on things like cucumber like an unrefined moromi miso.

During wartime in the Showa period (1926 to 1989), the number of producers of Edo sweet miso declined, since production of Edo sweet miso was halted because it was deemed a luxury item. Many called for its revival after the war, and it began to be produced again, and the taste of Edo is still alive today.

There are many other things that originated in Edo culture, that evolved and became popular, and then became firmly entrenched in our lives. One of these is cookbooks, which first became popular among the general public during the Edo period.

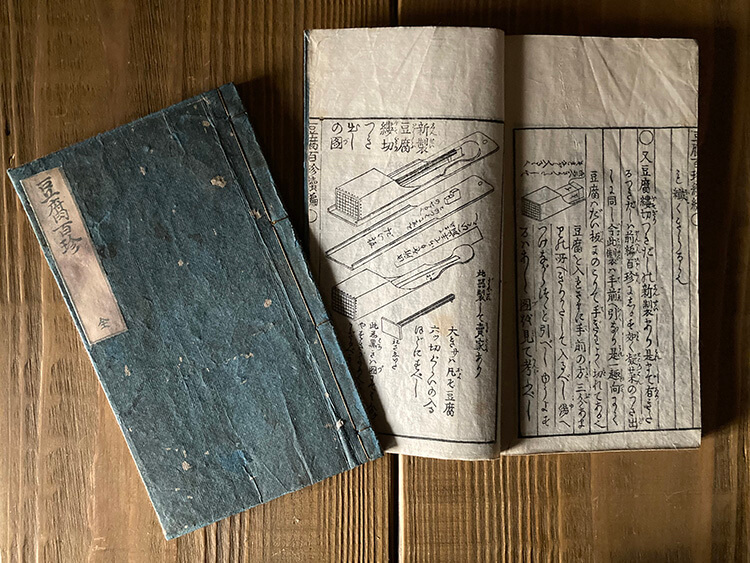

“It was in the Edo period that ordinary people began to read cookbooks, which had previously been aimed at professional chefs. The first cookbook was Ryori Monogatari [Cooking Tales] published in 1643. It was followed by the publication of more than 230 cookbooks. One of these, published in 1782 in Osaka, was Tofu Hyakuchin [100 Magnificent Tofu Recipes], which really popularized cookbooks. Tofu Hyakuchin contained recipes and reviews of 100 tofu dishes and was an enjoyable read as well. It was later published in Edo and became a huge best seller. After the release of the sequel, Tofu Hyakuchin Zokuhen, the following year, it became a fad to collect 100 recipes related to a certain ingredient, such as daikon radish or eggs. The readership of these collections was apparently massive. It’s fun to imagine the women who surely made dishes following these cookbooks, sharing them with older women and young people living in the same row houses.”

Ukiyo, herself, has written Simple Healthy Recipes Made with Fermented Food: Learning from Edo Cookbooks, a collection of some of these Edo period recipes. The book presents dishes using fermented foods available today, and all the recipes are delicious and easy to make.

“I regularly make dishes from this book. The one I make the most is shiran tofu [fragrant tofu], which was published in Tofu Hyakuchin Zokuhen. It’s a tofu dish that uses ground white sesame and white miso, and it’s truly delicious. Another popular dish is tamago fuwa fuwa [fluffy egg soup]. Tamago fuwa fuwa was reportedly served at Tokugawa Clan banquets and a favorite of Kondo Isami, commander of the Shinsengumi elite swordsmen.”

The fermented food recipes that were loved by the people of Edo still grace our tables today. This fact lends a sense of profundity to the food and perhaps a slightly odd sensation. Ukiyo says that there is much we should take away from Edo cooking and Edo’s food culture, especially in today’s world.

“Without question, the simple, highly nutritious, healing food they consumed is something we should learn from. But there are many other aspects we should emulate, for example from the perspective of food loss. The people of Edo rarely threw away any part of the ingredients they had. If you bought a whole fish, you would first eat it raw and the parts you couldn’t finish, you would preserve by marinating them in soy sauce or miso. This way of preserving the fish meant you could eat all of it while still being delicious.”

They even made use of the water used to wash rice.

“Because the technology to polish rice was still immature, the water used to wash rice was very concentrated. Adding natural salt to this water and using it to pickle vegetables results in lightly salted pickles, as the water will ferment into lactic acid. This doesn’t take much effort, your vegetables last longer, it’s economical, it reduces food waste, and it’s good for your bowels. It’s all good. I personally make it every day, and it’s a cooking technique that excites many people at workshops and other events.

“If you go to a convenience store nowadays, you can easily get prepared and precooked meals. Frozen food has gotten better too. Nevertheless, there are many excellent aspects of the food culture and recipes of the Edo period that we should incorporate today, such as highly nutritional healing foods that are simple to prepare and are both delicious and good for the environment. I would love for more people to take a look at the food of the Edo period.”

“Add and dissolve one teaspoon of natural salt for every 200 mL of concentrated water from the second and third rice rinses, and then simply soak cut vegetables in the pickling brine, seal the containers, and store in the refrigerator. (If adding mushrooms or broccoli, boil the pickling brine once, and after it cools, store in the refrigerator.) The lactic acid fermentation will gradually take place for about two weeks, so you can eat the vegetables anytime.”

Edo Culinary Culture Research Institute representative and period novelist

Edo Culinary Culture Research Institute representative and period novelist

Born in Osaka and a graduate from the Design Department of the Osaka University of Arts, Kuruma has a deep knowledge of Edo culture, particularly ukiyo-e and Edo cuisine. She studied screenwriting under film director Shindo Kaneto and is currently studying under author Tsuge Itsuka. She received an Ohtomo Shoji Award at the 18th Japan Writers Guild Awards. On March 15, 2024, she opened Ukiyo’s Kitchen, an Edo-style kitchen studio, near Saitama University.

Recent works include Kisanji Hokusai (Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha),Tsutajyu no Oshie (Futabasha Publishers), Tengai no Umi: The Story of Three Generations of Vinegar Makers (Ushio Publishing), and Simple Healthy Recipes Made with Fermented Food (Tokyo Shoseki).

http://kurumaukiyo.com