Suyakame: A Miso Brewery Exploring the Boundaries of Miso

Nov 21,2024

Suyakame: A Miso Brewery Exploring the Boundaries of Miso

Nov 21,2024

At least once in your life

Go worship at

The Zenkoji Temple.

So it is said of the Zenkoji in the city of Nagano, the venerated Buddhist temple that attracts visitors in droves from all over Japan. Not far from the great temple is Suyakame Honten, which has been making miso the traditional way since 1902. In 1996, this historic miso manufacturer opened an outlet on Zenkoji Nakamise Street, the shop-lined avenue leading to the temple. The outlet is popular for its takeout offerings, and Suyakame is a name that often pops up on food crawls of the street. By bringing out a steady stream of processed miso products, this long-established but enterprising company has shown the world new ways to enjoy the magic of miso. We talked with its president Aoki Shigeto, the driving force behind its expansion.

Aoki Shigeto’s grandfather Aoki Kamekichi, the founder of Suyakame Honten, was born into a family of joiners-cum-farmers who lived near the Zenkoji temple. He had ambitions of making a living in business. At seventeen, therefore, he started an apprenticeship at one of the oldest miso makers in Shinshu (as Nagano Prefecture is historically known): Suya Kyuemon Shoten in Komoro (now Sukyu Shoten, makers of Yamabuki Miso). There he mastered the art of making soy sauce and miso. He was lauded by all for his hard work and dedication and, at thirty-two, granted permission to set up his own store.

“The new store’s name was ‘Suyakame,’ formed by combining the ‘Suya’ of Suya Kyuemon Shoten with the ‘Kame’ of his own name Kamekichi. My grandfather struck out on his own in 1902 making and selling soy sauce, and after just ten years he was able to erect a company building, which then served as Suyakame’s headquarters. The rice paddy in front of the store had been sold to make way for a new street, and my grandfather was also a successful fuelwood dealer and flour miller.

“Then in 1914 World War I broke out. My father, the second Kamekichi, fought in the war, then took over the business after returning from the front. That was in the year after the war ended. In those days Shinshu miso (as miso from Nagano is called) was just beginning to sell in the Kanto region, and in my father’s day the company made a new beginning as a miso dealer.”

Aoki Shigeto took over the family business as its third head in 1975. He had spent the two preceding years apprenticing at Suya Kyuemon Shoten as his grandfather and father had done.

“That two-year apprenticeship was to prove an invaluable experience in running the business. If I hadn’t done it, Suyakame might not be where it is today. I learned all about selling by mail order and acquired clients in Tokyo. I was able to build a personal network. My boss even introduced me to my wife. That was maybe the best thing of all [laughs].”

When Shigeto joined Suyakame, the business wasn’t in debt and looked like a thriving concern, at least judging from its balance sheet.

“In fact, consumers were eating less and less miso, and sales were in steady decline. Our wholesale-oriented business model, I felt, was bumping up against its limits. We diligently went about making miso, but all I noticed were the downsides: a lack of distinctiveness, a limited customer base, an antiquated building, rusty equipment, an aging workforce. But that’s why I was able to make bold changes without caring what anybody else thought.”

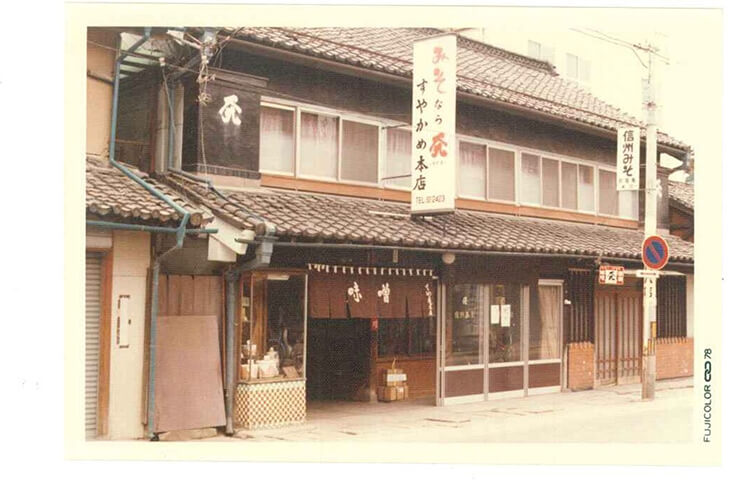

Suyakame around the late 1970s, when Shigeto took over the business. A wide-fronted building overlooking the street, it remains unchanged today.

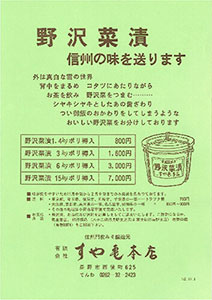

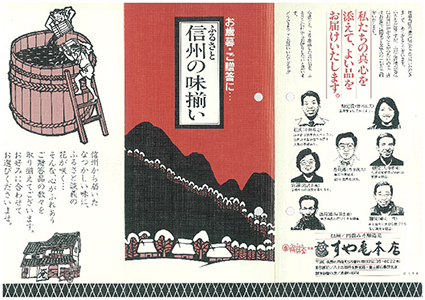

“We jettisoned the idea that because we were in the miso business, all we had to do was make miso. In 1976, we launched a mail-order operation from our headquarters. We had no idea what to make at first. We started out by offering miso and miso pickles, but neither sold well. I guess they were too run-of-the-mill. Then we brought out pickled nozawana, a type of mustard green Nagano is famous for. That was our first big hit, though I have to admit I wondered why it sold so well. The dried soba noodles we released the next summer also sold pretty well. I then realized that virtually any Shinshu specialty would sell. It didn’t have to be miso.”

Suyakame also turned its energies to selling apples and sun prunes supplied by nearby farmers, as well as pickles like white melon preserved in sake lees and Togakushi Takuan pickled daikon. The pickles were made in house based on the recipes of Shigeto’s mother, Haruko.

“Our pickled nozawana was made by salting nozawana greens, then adjusting the flavor with shiro (white) soy sauce, katsuobushi (dried skipjack tuna), and kelp stock. Togakushi Takuan was made by sun-drying a type of pickling daikon called Aokubi Shina Daikon, then pickling it over the winter with rice bran, kelp, and natural salt containing nigari (bittern). Both were very ordinary foods with the plain taste of old-fashioned homemade fare. The one thing we could claim was that they were free of additives from the start, since my family never used umami seasonings like amino acids. People said various things about our pickles when they first came out. They have an off color. They don’t last. They don’t have enough umami. But we stuck to our guns, and so here we are today.”

Suyakame also embarked in earnest on developing processed miso products. The biggest sellers were each spun out into an entire series. The first product to appear was Walnut Miso, and when it sold well, the company commercialized a series of sixteen miso offerings for serving with rice. These included fuki (Japanese butterbur) miso, buckwheat miso, yuzu miso, and curry miso. There was also the ume series, which included Kanro Ume, Omusubi Ume, and Umezuke, and the Taste of Home series, which included “Kuromamekko” black soybeans, soy sauce beans, chopped miso pickles, and fried nozawana.

“Our list of customers steadily grew, and we started sending out direct mail postcards four times a year and mailing catalogs. We would get loads of orders during the year-end and summer gift-giving seasons. We were so short-handed that my wife and I would work until late at night writing names and addresses on the labels. I remember it well.”

Left and center: Pickled nozawana was a huge hit when Suyakame commenced mail-order sales in 1976. A steady stream of Shinshu specialties, pickles, and processed miso products followed. The illustration shows a direct mail postcard and pamphlet from the time. Right: Walnut Miso, the company’s first processed miso product. It came in what looked like a jam jar, which was new and unusual at the time. That made it all the more popular.

Mail orders steadily drove the company’s growth, and in 1985, a decade after Shigeto came on board, Suyakame was able to renovate its dilapidated headquarters building. At that point it opened a refreshment corner serving food and drinks called Shokumi-dokoro . The star of the menu: Yaki Musubi (grilled rice triangles) coated in miso.

“We modeled our renovations on Chikufudo, a confectioner in Obuse, and Mitsutaya, a miso specialty store in Aizuwakamatsu. I must have visited them dozens of times. While both had long histories, each had succeeded brilliantly at doing something new. Chikufudo offered freshly cooked rice with chestnuts, which was also available to go. Mitsutaya started a ‘Miso Dengaku Corner’ in store serving miso dengaku: various ingredients glazed with miso and grilled on a skewer. That’s where I got the idea for the refreshment corner and the Yaki Musubi coated in miso. When you dropped by Mitsutaya, the aroma of the miso from the skewers on the grill smelt just wonderful. We hoped it would prove equally effective in attracting customers to our place [laughs]. We also turned to them for advice. Chikufudo had redone their store a little before our renovation project started, and their new place looked magnificent, so I got them to put me in contact with their designer. I often say that imitation is part of art. It’s important, though, to weave in your own ideas rather than simply copy outright. In our case, we want people to eat our miso, so I’m constantly asking myself how to make the miso connection. Also, learn from people in the same line of business far away or in a different line of business nearby. Get them to take you under their wing. Because you don’t compete with them, they’ll be more than happy to mentor you.”

Left: Popular items at the flagship store. From left: Monzen Amazake (a sweet fermented rice beverage), Shoyu Beans, Walnut Miso, Miso Mayonnaise.

Right: The star of the menu at the Shokumi-dokoro eatery is Yaki Musubi (grilled rice triangles) coated in miso. Especially popular is the Yaki Musubi Basket, which comes with miso soup, pickles, and a seasonal side item.

A definite methodology can be discerned behind the many products that Shigeto has launched. Find something that is currently being talked about or having a moment. Then combine it with miso to create a totally original item. Moreover, all his creations are familiar foods you could eat every day, and they exude the artless simplicity you associate with Shinshu. He has released over three hundred products and services, through quite a few soon disappeared.

“We tried offering ‘Omusubi (rice triangle) Delivery’ à la pizza delivery, but that didn’t last long. When we got an order, it often had to be delivered exactly when we were making food at the store. And my employees sometimes told me I’d been too quick off the mark, as in the case of miso-flavored rusk and miso-flavored game meat. There were a fair number of products that maybe would have sold better if they’d come out six months or a year later.”

Having started retailing directly to consumers as well as taking orders by mail, Shigeto was now on a roll. In 1996, a decade after headquarters was renovated, he opened an outlet on Nakamise Street. This was the Suyakame Zenkoji Store. His twenty years of unrelenting hard work since joining the company had finally paid off.

Left: The shop inside company headquarters. The shelves are packed with miso and processed miso products.

Right: The Zenkoji Store is in the foreground on the right. Its Miso Soft Serve and Yaki Musubi are as popular today as they were when they first appeared 26 years ago. They’re both Zenkoji Nakamise Street classics.

Zenkoji Nakamise Street, which runs from the Niomon Gate to the main Sanmon Gate of the Zenkoji temple, is flanked on both sides by some three dozen restaurants and souvenir shops. Like the approach to many great Buddhist temples in Japan, it’s always bustling with people. Suyakame’s Zenkoji Store is at the near end of Nakamise Street after you pass through Niomon Gate.

“The place was only nine tsubo [approx. 30 square meters], so it was tiny. It sold miso and processed miso products. We also put considerable effort into takeout food and drinks, including Yaki Musubi, Miso Soft Serve ice cream, and Amazake, a sweet fermented rice beverage. Back in those days there weren’t that many places on Nakamise Street that offered takeout. The Yaki Musubi was wrapped in a strip of nori seaweed to create a nice snack to munch on while strolling in the vicinity. I’ve got a sweet tooth, and I happened to visit an ice cream parlor in Tokyo that was popular at the time. I lined up to get my ice cream, and when I ate it, it contained carrot and sweet potato. That got me thinking that ice cream could just as easily be made with miso. And so Miso Soft Serve was born. The store was at the very end of Nakamise Street, so I wondered whether it would even be commercially viable. But that’s a tourist attraction for you. The most important factor in opening a store is whether it’ll attract customers, and on that score, I needn’t have worried at all.”

Miso Soft Serve was an instant hit as soon as the store opened. It was even featured in the media as something new and unusual. One year when the sacred image enshrined at the Zenkoji was exhibited to the public, three thousand miso ice creams were sold in a single day during the spring Golden Week holiday. That’s a record. Indeed, Miso Soft Serve became so well known that it had a knock-on effect on the company’s entire business.

“There was a jump in mail orders. Customers would ask us to send, say, such-a-such a product because they’d bought it at the store and it tasted great. Our list of mail-order customers grew by the year. We also saw an increase in business with wholesalers wanting to stock miso products sold at the Zenkoji Store. That would have been unthinkable back in the days when wholesale transactions dominated our business and we had to make the rounds hat in hand.”

Left: Miso Soft Serve has a subtle twist of miso. Its light, creamy texture and dash of saltiness are truly addictive.

Right: The Zenkoji Store’s Yaki Musubi is wrapped in nori seaweed to create a handy snack to go.

Suyakame steadily expanded into mail order, retail, and food services. But before the Zenkoji Store opened, it faced tough times. Behind the scenes, it was struggling.

“Things were great for the two or three years immediately after we rebuilt our headquarters in 1985, but the following decade was the most difficult in our history. We faced a slew of problems: staffing issues, cashflow issues, product issues, business succession issues. Our biggest problem was staffing. Our focus on mail order, retail, and food services required a lot of people. The company had four or five people when I came on board, but over the next ten years our workforce grew to twenty. Twenty-four people joined the company only to quit. We managed to develop channels for hiring young people, which got around the problem of an aging workforce. But when it came to staffing, the biggest obstacle was me, the president. I was totally focused on sales and in too much of a hurry. I was oblivious to the importance of employee training, so employees got left behind. But then I realized it was all my fault, and during this difficult time in our history, I studied business administration and HR more than ever before.”

Shigeto took various steps to boost employee motivation. He established an incentive program to encourage employees to obtain qualifications. He set up an employee education program with the goal of entering contests like miso competitions and the Best Customer Service Rep contest. He arranged off-site training.

“I wanted our employees to study. I believed it was incumbent on the company to create an environment that boosted motivation. After one of our salespeople qualified as Retail Sales and Management Specialist, they went about their job with even more verve, and that had a positive ripple effect on the rest of the team. Immediately after that, they also started seriously working on making miso. When it comes right down to it, the reason we got into mail order and retail sales in the first place is because we want people to eat more miso. We’re a miso dealer, after all. So this person figured they needed to learn more about miso. They wanted to bring our miso to customers with greater confidence. ”

The going has sometimes been tough, says Aoki Shigeto. He shared his reminiscences while flipping through neatly filed old catalogs and direct mailings.

Suyakame’s miso can be classified into three types depending on the occasion when they’re used: everyday miso, slightly fancier miso, and the ultimate miso.

Everyday miso is exemplified by Kogane, a mild-tasting miso with a rich aroma. It’s lovingly fermented using generous amounts of Japanese-grown soybeans and koji malt produced from Japanese rice. It has the golden yellow color characteristic of Shinshu miso. Soft and a cinch to use, it’s Suyakame’s most popular miso.

The slightly fancier type of miso is exemplified by Koshihikari. Made with Japanese-grown Koshihikari rice, prime-grade domestic Japanese soybeans, and Okinawan Shimamasu salt, this sumptuous miso is patiently aged in Suyakame’s wooden barrels. Possessing a deep lustrous brown color, it is far and away the best-smelling miso in the entire Suyakame lineup.

The ultimate miso is epitomized by Aspiring to Be the Ultimate Miso. This started being made in 1998, and it goes on sale once a year by reservation only. This year (2024) marks its twenty-sixth iteration. What kind of a miso is it exactly?

“The biggest difference is that it’s made with the choicest rice and soybeans. We only use pesticide-free ingredients. The rice, for example. At first we ordered it from a farm in Saku that practiced rice-duck farming, but caring for the ducks was a lot of work. Now the weeding is done by machine. But it has to be done at least three times during the season, which keeps the farmer really busy. It’s a similar situation with soybeans. At first we ordered them from a farmer in Matsumoto, but weeding took so much time and effort that in the summer our people would take turns going to help. We later found a farmer in Tokachi, Hokkaido. Their farm is huge. They even clear all the weeds between the plants using the latest heavy-duty weeding equipment. These days we get our beans from them.”

Left: Suyakame’s most popular miso Kogane (left) and its best-smelling miso Koshihikari (right).

Right: Aspiring to Be the Ultimate Miso, made without compromise using only the choicest ingredients.

Suyakame is dedicated to delivering safety and peace of mind in its products. Since 1997, it has been a member of the Good Food Production Association , an organization of producers, vendors, and consumers working together to ensure a safe, secure supply of great-tasting food for the next generation. The company’s commitment to food safety is evident in how it goes about producing Aspiring to Be the Ultimate Miso: by visiting farms in search of the finest ingredients. Manufacturing this miso even led it to repair or replace its entire set of wooden barrels.

“Starting in 2013, we had two new barrels made and repaired another six. The job took six years to complete. Traditional Japanese wooden barrels are wide at the top and narrow at the bottom and bound with bamboo hoops. Making or repairing them requires a skill set only possessed by a professional cooper. Large tanks for fermenting miso are typically made of stainless steel or reinforced plastic. As far as I know, there’s only one company left that knows how to make and repair wooden barrels.”

Repairing the six wooden barrels, incidentally, cost as much as a luxury car. But the price was worth it, says Shigeto.

“A wooden barrel isn’t just a container. It plays the starring role in the fermentation and aging process so vital to miso. The yeast living in the factory colonizes the barrel, creating the flavor and aroma characteristic of Suyakame miso. It yields a taste you don’t get from a stainless-steel tank. Now that we’ve repaired the barrels, hopefully they’ll remain in good working condition for the next hundred years. They still require maintenance, though. For example, after fermentation is completed each year, the barrels are emptied of their contents and flipped over .”

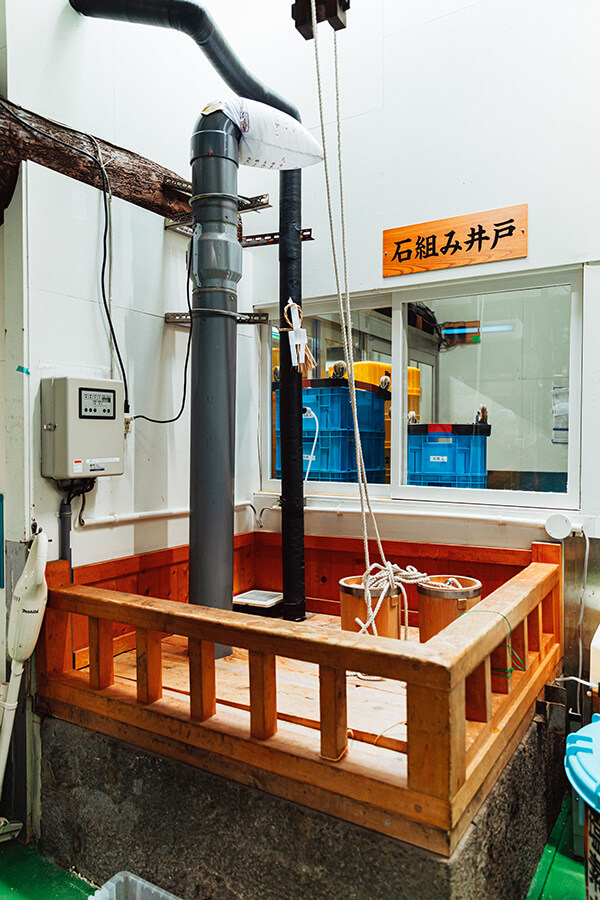

The massive barrels aren’t the only thing that would surprise any visitor to Suyakame. In the middle of the factory is a stone well built over 120 years ago. The crystal-clear groundwater it supplies comes from the Susobana River system, and it’s never dried up. Suyakame miso is made using this natural water supply.

“Of course, it’s not just a matter of ingredients and equipment. Here at Suyakame, we also value the skills of our seasoned craftspeople. After all, the traditional technique of kanjikomi or ‘cold preparation’ — preparing the miso ingredients for fermentation in winter — requires consummate craftsmanship. You have to know how to work in harmony with nature.”

Left: The well in the factory, which hasn’t dried up once in 120 years.

Right: Among the things Suyakame most values are the dedication and skill with which its people apply themselves to making miso.

The stone well and wooden barrels, reminders of Suyakame’s 122-year history, are still in use. They remain central to the company’s miso-making operations today. Other facilities are, however, updated or repaired virtually every year. A fair amount of the equipment is new. Here old and new coexist in harmony, giving the place a distinctive air. The factory is usually closed to visitors, but there are special occasions when you can get a look inside.

“Two days a year, we hold an event called the Miso Factory Open House when the factory is open to the public. People are amazed when they step inside and see the well and the barrels. Our products are sold at a discount during the event. There’s a grilled rice triangle making demonstration and tasting and a miso-making class. People also get to pound rice in a mortar to make rice cake. There’s something for everyone to enjoy.”

The event is organized by Aoki Shigeta, Shigeto’s son, who will take over as Suyakame’s fourth president in the near future. He started working as coordinator of corporate planning two years ago.

“It’s a good idea to send your successor elsewhere to gain experience, but in my case, I was a bit late to call him back home. There’s a lesson here on grooming a successor: don’t let him join a company that’s too big [laughs]. Still, I’m looking forward to seeing what kind of company Suyakame becomes once I hand the reins to Number Four.”

Left: Held twice a year, the Miso Factory Open House attracts a huge turnout, the more so because the factory is not usually open to the public.

Right: The event features activities galore, including food tastings and hands-on miso-making sessions.

Shigeto’s corporate motto consists of two maxims drawn from a classical Chinese text of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

“The first is shinmi kore tan, meaning that the most authentic flavor is a simple one that never grows boring. None of the misos or processed miso products that we deal in may be particularly rare or unusual. But you can eat them over and over again without ever tiring of them. We’ve made countless processed products using miso. That’s how versatile miso is. It’s what makes miso so wonderful, and we want to keep spreading the message about it. The second maxim is fueki ryuko. Fueki means the eternal and unchanging; ryuko means the transient, what changes with the times. For us, it’s important to continue exploring the possibilities of miso as lifestyles and tastes evolve over time. Meanwhile, we’re committed to preserving the fermented foods that have long underpinned the Japanese diet and safeguarding the goodwill and miso culture we’ve built up over the last 120-odd years. That, I believe, is our mission.”

President, Suyakame Co., Ltd.

After graduating from Keio University, Aoki Shigeto worked for two years at a miso company in Tokyo. In 1975, he took over the family’s miso-making business, which was already over seventy-five years old, becoming its third president. He expanded from manufacturing and wholesaling miso into three new fields: mail order, retail, and food services. In 1996, he opened the Suyakame Zenkoji Store. Its takeout snacks, including Yaki Musubi (grilled rice triangles) and Miso Soft Serve, have become Zenkoji Nakamise Street classics. On a personal note, Shigeto was a member of the cycling team at university. He spent forty years cycling the entire length of Japan, completing the feat at age sixty. Now that he is over seventy-five, watching movies is what he loves to do most.

No.1

No.2

No.3

No.4

No.5